Critically examining the evidence for there having been a single paying passenger on Titanic's delivery trip from Belfast to Southampton.

Introduction

Certain stories within the greater Titanic canon have become legends in their own right. Some, such as Isidor and Ida Straus refusing to be separated at Lifeboat No. 8, are based solidly on facts. Others were considered factual for many years, before being rewritten or disproven altogether. One example concerns the fate of Thomas Andrews.

For upwards of a century, Andrews was depicted as spending his last moments alone in Titanic’s first-class smoking room, his arms folded, a stunned expression on his face, his lifebelt carelessly discarded on a nearby chair. Only relatively recently did detail-conscious researchers show that this was not the last sighting of Andrews, who appears to have remained actively engaged in the closing moments of his and Titanic’s lives.

(Daily Graphic, 17 April 1912)

What other stories-within-the-story might also prove to be false or misinterpreted? For over 20 years, since I first read of it, one peculiar report has bothered me. Titanic victim Wyckoff van der Hoef, a first-class passenger, supposedly boarded the new White Star giant in Belfast, Ireland, remaining onboard during her sea trials and subsequent delivery trip…as an ordinary passenger.

This just seemed “off,” somehow. I vowed that if I ever could do so, I would attempt to determine the story’s validity, if only to satisfy my own curiosity.

In August 2022, I finally undertook the project. While the passage of nearly 112 years and certain documents’ apparent nonexistence have made impossible a definitive answer as to whether this unique journey from Belfast to Southampton occurred, I believe I have discovered sufficient new circumstantial evidence to cast serious doubt on the claim. In this article, I hope to document and explain my findings, leaving readers to weigh the evidence and form their own conclusions.

What does the legend say?

The basic story has 61-year-old Wyckoff van der Hoef departing from New York in March 1912, his destination being Belfast, Ireland. He planned to visit family living there and, possibly, to conduct some business. On April 2, 1912, van der Hoef boarded Titanic in Belfast before the successful completion of her sea trials. (Since Titanic never docked in Belfast after its departure on trials, the only alternative would have been for him to meet the ship in the dark after trials were completed, and then board the lighter that brought out some late or overlooked kitchen equipment and furniture.) As the only fare-paying passenger, he would have had a unique perspective of the journey from Belfast to Southampton.

Once Titanic reached Southampton, the story becomes very vague. Van der Hoef either disembarked from the ship, staying in a hotel until re-boarding on April 10, or for the next six days, Titanic served as his de-facto hotel, from which he could come and go as necessary.

On April 15, this unusual passenger – who possibly had spent nearly two weeks aboard Titanic – was one of the tragedy’s 1,496 victims. Researchers thus were deprived of a rare, intimate testimony of the ship’s too-short life.

What is the evidence that this happened?

Primary source evidence supporting the story of a paying passenger boarding Titanic in Belfast is all but nonexistent. In fact, at present, the only indications of van der Hoef making a Belfast embarkation come from two brief notices in the Belfast News-Letter.

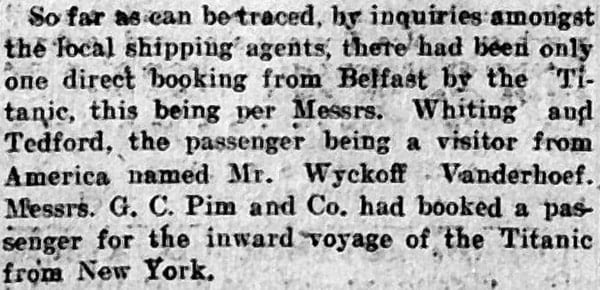

The first, from April 15, 1912, states:

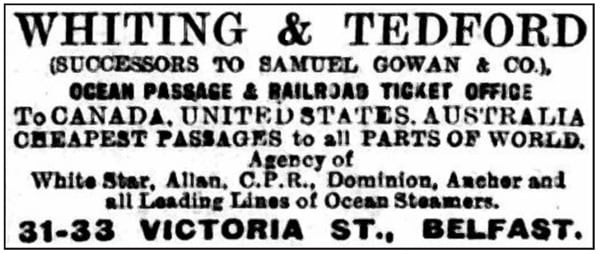

“As far as we can trace, by inquiries amongst the local shipping agents, there has only been one direct booking from Belfast by the Titanic, this being per Messrs. Whiting and Tedford, the passenger being a visitor from America named Wyckoff Vanderhoef [sic].”

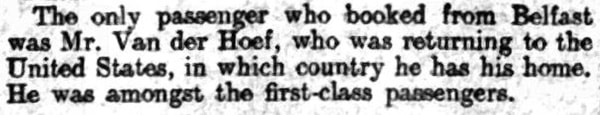

The second notice appeared in the News-Letter two days later, April 17:

“The only passenger who booked from Belfast was Mr. Van der Hoef, who was returning to the United States, in which country he has his home. He was amongst the first-class passengers.”

The story of van der Hoef boarding as a passenger at Belfast likely arose from the April 15 notice’s wording, with “one direct booking from Belfast by the Titanic” being interpreted literally to mean he not only booked but also boarded the ship and departed directly from Belfast. But a careful reading of the notice in its original context does not say that; it states only that van der Hoef booked directly from Belfast. Similarly, I could book a flight directly from my hometown’s travel agent, but that wouldn’t mean the airport from which I would depart is there.

(British Newspaper Archive)

(British Newspaper Archive)

Rereading the second notice, from April 17, one sees the wording is much clearer than that of the earlier notice, and the meaning is plain: Wyckoff van der Hoef booked from Belfast, and nothing more.

A plethora of circumstantial evidence calls this story further into question.

The reasons for van der Hoef’s journey now are known.

The reasons behind van der Hoef’s 1912 European trip have always been vague, but now I can provide absolute clarity: The journey’s purpose was two-fold, combining the undoubted pleasure of visiting his sister and her family in Belfast with an important business mission in London.

.jpg)

By February 1912, the Williamsburg City Fire Insurance Company, of which van der Hoef was secretary and the largest stockholder, was experiencing serious financial difficulties. Williamsburg’s directors ultimately voted to sell the company’s stock outright to a larger company, setting its hopes on London’s Alliance Assurance Company, controlled by Lord Nathan Mayer Rothschild and funded by the Rothschild millions. Van der Hoef thus was sent to Europe – “much against his inclinations” – on the company’s behalf to meet with Rothschild and seek his aid. Presumably, the meeting’s date and time had been arranged before his departure. Van der Hoef left New York aboard Olympic on March 23, 1912. His voyage would have terminated in Plymouth, England, assuming he intended to go to Belfast first.

Via wireless, Olympic reported she was to make Plymouth by 1 p.m. on Friday, March 29. The morning editions for Saturday, March 30 confirmed that the vessel had made port the previous day.

Arriving at the home of his sister, Mary C. Long, at 5 College Park East in Belfast on March 29, at the earliest, would have given Wyckoff scarcely three days to spend with his family, since Titanic’s sea trials originally were scheduled to commence on April 1, with the ship presumably departing Belfast that evening. This reunion’s almost painful brevity is apparent, for this was Wyckoff’s first visit to his Irish family since the death of their mother, Isabel Jane van der Hoef, on September 27, 1904.

(Wikimedia Commons)

She had lived with Mary’s family in Ireland for several years and had been buried in Belfast City Cemetery; a visit to her grave presumably was on Wyckoff’s itinerary.

Why do I doubt the story?

There were no advertisements for a Belfast embarkation, nor, specifically, for the sea trials and post-trials departure.

Quite simply, there are no known advertisements for prospective passengers to board Titanic in Belfast. It had never been a point-of-embarkation for White Star ships.

Furthermore, no known newspaper notices reported the time of Titanic’s sea trials, their duration, or when the new ship would leave Belfast, once trials had concluded.

Additionally, Titanic did not receive her passenger certificate until the completion of her trials, “good for one year from today, 02.04.12.” However, maritime historian Mark Chirnside points out that this was a passenger certificate as a foreign-going emigrant ship, and because the delivery trip to Southampton was entirely within U.K. waters, a certificate might have not been necessary. No passenger list would have been required, either.

(Bruce Beveridge et al, Titanic: The Ship Magnificent, Vol. 2)

It should be remembered that a passenger sailing from Belfast would have been an extraordinary occurrence. To the knowledge of Chirnside, who has studied the White Star Line for many years, it would have been unprecedented.

Regarding the sea trials’ timing, the question arises whether Wyckoff could get to Belfast in time to visit with his family at all, before boarding Titanic. Olympic made Plymouth on the afternoon of Friday, March 29. How quickly, then, could Wyckoff have procured passage on a ferry from Plymouth to Belfast or, alternatively, Plymouth to Dun Laoghaire (pronounced “Dunn Leery,” the port for Dublin) and then by train to Belfast? Though ferry schedules found thus far in digitized newspaper archives are undoubtedly incomplete, the area’s most prominent ferry service appears to have been that of the Clyde Shipping Company, Ltd. Its July 16, 1912 advertisement indicates the company ran a ferry service from Plymouth to Belfast every Monday. As stated, Wyckoff arrived on Friday. Although this advertisement was dated three months after his arrival, only rarely did ferry schedules change.

The implication is that Wyckoff might have been unable to get to Belfast from Plymouth before Monday, April 1, the original date of Titanic’s sea trials. The ship’s departure to Southampton presumably would have been in the evening of April 1, giving him less than a single day with his family – and only one additional day after the sea trials’ unanticipated delay to April 2 – before he would take Titanic to Southampton…where the vessel would remain at its pier for nearly one week. Of course, another company’s ferry service might have offered transportation sooner, but advertisements saying so have not turned up.

It is important to note the new ship was never opened to public inspection, either at Belfast or Southampton, due to ongoing outfitting and other preparations onboard.

In a letter dated April 1, 1912, William A. Jeffery, controller of the à la carte restaurant, told his mother: “We are doing very little here except worry around trying to get various jobs done, and until the workmen are out of the way we can’t touch anything.” On March 30, the Southampton Times and Hampshire Express informed its readers, “There will be no public ceremony of any kind. The Titanic will enter the Solent without the blare of trumpets or the display of the silver oar. A lot of work will have to be done on board the ship during her week’s sojourn at the Docks, and it will be impossible to allow people on board except on business.” If the public was not allowed even a peek aboard Titanic, would a passenger have been granted the privilege to sail on her or remain on board before the April 10 departure from Southampton?

So far as is known, no surviving Belfast crew member recalled an ordinary passenger being aboard for the delivery trip.

When Titanic departed Belfast, she had aboard thirteen men travelling as passengers in first- and second-class. Of these, ten comprised Harland & Wolff’s special guarantee group; all would continue the journey across the Atlantic, and perish to the last man. In all departments, 421 known crew members were on board for the delivery trip. Additionally, Harold Sanderson, a White Star director, and Board of Trade surveyor Francis Carruthers were aboard in first class, as was naval architect Edward Wilding. None of these men, who did not continue their journeys beyond Southampton, nor any of the crew who continued with the ship and survived the sinking, are ever known to have mentioned a fare-paying passenger being among them for the delivery trip. The answers Wilding gave to hundreds of questions at the British and limitation of liability hearings revealed him to be a keen observer of details. How would a passenger, virtually unheard-of on a trial trip, escape his notice or his mentioning?

Second Officer Charles Lightoller, Third Officer Herbert Pitman, Fourth Officer Joseph Boxhall and Fifth Officer Harold Lowe, all aboard during the delivery trip, later testified at the American and British inquiries. None mentioned a passenger then being aboard, nor did Marconi operator Harold Bride. But, to be fair, none were asked that specific question.

Another reasonable question is would there have been a steward aboard to serve a first-class passenger and service his cabin? Three first-class stewards are known to have signed on in Belfast. Two of them, George Bailey and Charles Back, signed on again on April 4, so it’s possible they might have remained onboard while Titanic was in Southampton. Unfortunately, none of the three stewards survived the disaster to recount their activities.

Another point to consider: If Wyckoff were truly Titanic’s first paying passenger, wouldn’t the press have sought his thoughts on the new ship? Although prior to the disaster, Titanic did not command the same press attention that the Olympic had the previous year, it is hard to imagine that reporters wouldn’t have tried to get a description of the new leviathan, especially since the public was barred from inspecting her.

There is no known White Star Line documentation indicating a passenger boarded at Belfast.

(National Archives of the United Kingdom, Kew)

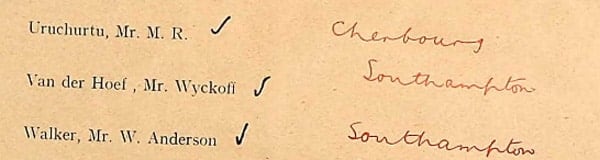

To date, no documentation from the White Star Line has been found to indicate that an ordinary paying passenger was aboard Titanic when she departed Belfast. Last year, this author came across a document headed “Lists C & D, Passengers Drowned” held at the United Kingdom’s National Archives in Kew. The document consists of an incomplete Titanic passenger list comprising all three classes and likely was used by White Star or the Board of Trade in the tragedy’s immediate aftermath to denote which passengers had been confirmed as lost or saved. There are numerous handwritten notations by persons unknown, presumably, White Star or Board of Trade officials. Names of surviving passengers are marked-through, while many victims have small checkmarks beside their names. In several cases, a victim’s port of embarkation, as determined by the Board of Trade, is written in black ink beside the individual’s name. Beside Wyckoff van der Hoef is written “Southampton.”

While at first, this document seemed to offer absolute proof that Wyckoff had boarded Titanic in Southampton, it later became clear that the point-of-embarkation noted in ink was merely the embarkation point officially recognized by the Board of Trade. For example, Thomas Andrews, known to have originally boarded the ship in Belfast, is noted as having embarked at Southampton. Two separate voyages were involved: An “inland voyage” within the U.K. (Belfast-Southampton) and the transatlantic trip. This document regrettably pertains only to the latter.

Historian Daniel Klistorner notes that van der Hoef appears on the second and third proof copies of Titanic’s first-class passenger list. This indicates he booked his passage from Whiting & Tedford no later than Thursday, April 4, because on the next day, Good Friday, the agency’s office would be closed.

Allowing a passenger to board at Belfast would have shown extraordinary favoritism.

Since no passenger had been known to board a White Star steamship in Belfast, let alone during sea trials, and the new ship was not open to public inspection, the Line would have been showing van der Hoef extraordinary deference and favoritism, implying some direct connection between him and a high-ranking White Star or Harland & Wolff official.

So far as can be determined, no such connection existed. Williamsburg City Fire Insurance Company did not insure marine vessels, nor could I locate any evidence that it provided insurance coverage for White Star’s New York offices. If it did so, it would be an inordinate display of favoritism for such a tangential link to the company.

Wyckoff had travelled on several White Star vessels in the past, sailing on Germanic in July 1899, Celtic in August 1902, Majestic in April 1904 and Republic in January 1906. And of course, he traveled aboard Olympic in March 1912. However, many people were frequent, repeat White Star passengers. Even that level of patronage would not account for such special treatment.

Alliance Assurance, the company with which Wyckoff was to meet, did have £7,000 insured in Titanic: £5,000 on the hull and £2,000 in “merchandise.” However, it would have been a most extraordinary request for Alliance to have arranged the passage of an unconnected individual to come to London via Titanic’s delivery trip, simply to attend a meeting with them.

A passenger embarking at Belfast would have had to endure a myriad of difficulties.

As earlier noted, if van der Hoef did board in Belfast, he would have most likely done so before the sea trials commenced. Embarking Titanic at Harland & Wolff would have been difficult and dangerous. Once inside the tightly guarded gate, he would have had to dodge multiple tripping hazards from cables, plates and other ground obstructions, dropped or falling rivets, deafening sounds from riveting, etc. He then would have had to use the workers’ gangway to board Titanic. Harland & Wolff had liability while a visitor was in the yard, and while crossing over to the ship. Would they have been willing to risk their liability on an ordinary fare-paying passenger? And would a first-class passenger be willing to board among the shipyard workers?

If he was present on the trials, van der Hoef would have had to endure abrupt, hard turns, and crash-stops from full speed. While the other “civilians” on board likely were used to experiencing these, van der Hoef was not. Harland & Wolff was responsible for any potential injuries until the ship was handed over to the White Star Line, and all on board except the lone passenger presumably would be covered by workman’s compensation insurance (or the 1912 equivalent in the U.K.)

(Author’s collection)

Additional questions raise further doubts: How did van der Hoef learn of the postponement of the trials? Did he leave his family on the morning of April 1, only to return after going to the shipyard? Did he cart his luggage there and back? How would he learn the length of postponement? If he was a careful, methodical person, would he have chosen an uncertain path subject to the unpredictability of weather, risking a timely arrival for his London meeting?

The journey from Belfast to Southampton would not have been free.

If Wyckoff did travel aboard Titanic from Belfast to Southampton, he certainly wouldn’t have done so for free. So, there should be some indication of additional charges reflected in the total cost of his passage. For example, an overnight trip from Southampton to Queenstown cost £4. The Belfast-Southampton journey spanned two nights. With the valuable assistance of historian Daniel Klistorner, who specializes in Titanic’s passenger accommodations and their booking process, he and I made a comparison of the price Wyckoff paid with that paid by passengers known to be in cabins near his.

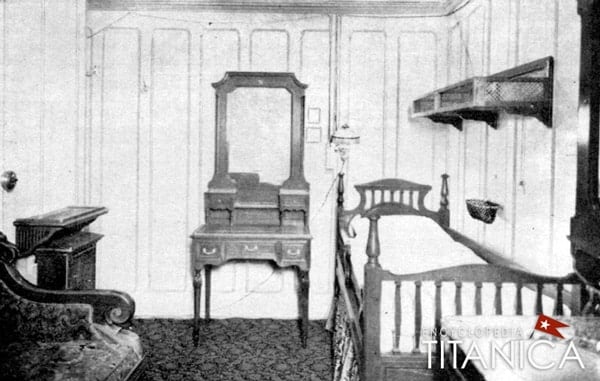

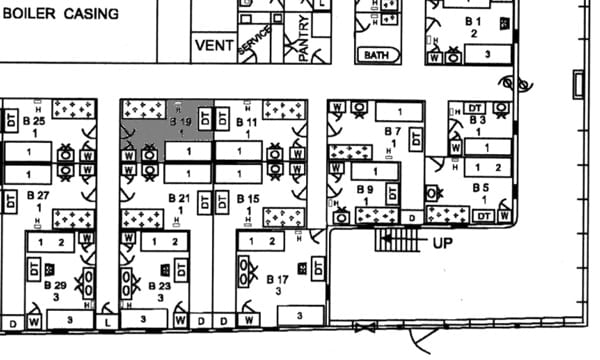

One would expect that Wyckoff paid more than his neighbors; yet, that does not appear to be true. He paid £33 10s (equivalent to about $5,400 in today’s U.S. currency) for ticket 111240. His cabin was B-19, a small inside room with no window. (This description of B-19 further weakens notions of any favoritism being shown.)

According to Klistorner, this cabin should have cost £30 at low-season fares or £42 during the intermediate season, which the April maiden voyage technically fell under.

Klistorner stated that the 10s in his fare most likely indicates he paid for train fare from London to Southampton. The train fare normally cost 11s, but when a first-class passenger paid above the minimum fare of £26, a discount of 1s was deducted from their train fare.

However, it seems that while some travel agencies charged minimum fares for tickets, others charged an intermediate-season fare, with the logic behind this not yet discernible. With the low-season price of £30 in mind, perhaps the remaining £3 Wyckoff paid was the fare for the Belfast-Southampton journey. However, this would have been an extremely low fare for a two-night journey, recalling the £4 cost for a single night to Queenstown from Southampton.

(Bruce Beveridge et al, Titanic: The Ship Magnificent, Vol. 2)

A comparison of the prices paid by Wyckoff’s neighboring passengers shows some surprising results. Harriette Crosby boarded at Southampton and occupied cabin B-26. Her fare cost £26 11s. Edward Austin Kent boarded at Cherbourg and occupied cabin B-37. His ticket cost £29 14s. Christopher Head, who boarded at Southampton and occupied cabin B-11, paid the intermediate-season price: £42 10s.

Thus, there was no vast difference between what van der Hoef and his onboard neighbors paid for their passages. It could be argued, however, that the Belfast-Southampton journey was billed separately from the Southampton-New York passage. If so, no evidence of such has come to light.

Neither his family nor friends were known to have mentioned Wyckoff boarding Titanic at Belfast.

His boarding at Belfast would have been an unusual detail that, it could be assumed, Wyckoff would have relayed at least to his wife, who, judging from her post-disaster comments to reporters, seems to have received some correspondence from him while he was away. And yet, neither she nor his friends ever mention such. In several instances, however, they do specifically mention Southampton as his embarkation point.

Oscar A. Baker, a prominent insurance and real estate man from Huntington, Indiana, was reportedly a friend of Wyckoff. Upon receiving word of his death in the disaster, Baker told the local press that Wyckoff “sailed from Southampton on the Titanic, first class…”

The claim filed at the limitation of liability hearings in New York by the Long Island Loan & Trust Company, executor under van der Hoef’s last will and testament, includes the following sworn statement:

“That on or about April 10th, 1912, the claimant’s testator [van der Hoef] took passage at Southampton, England, on the said steamship ‘TITANIC’ under a contract previously made between this claimant’s testator and the petitioner herein [the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company], for a valuable consideration paid to petitioner, by the terms of which contract petitioner agreed safely to transport this claimant’s testator as a passenger, together with his luggage and personal effects from Southampton to New York.”

Taking Titanic from Belfast to Southampton would have been counterproductive to van der Hoef’s mission.

Again, the primary purpose why van der Hoef was sent to Europe was to seek the Alliance Assurance Company’s aid for his own insurance company. Understandably, this meeting and its potential outcome were of the utmost importance. Would a trusted secretary who stood to gain or lose much depending on Alliance’s decision, choose an untried ship – assuming she would pass her trials – to get him to Southampton, whence he would proceed to London? What if the vessel had failed her sea trials? What if there had been another delay or a vital piece of machinery proved substandard or malfunctioned?

The meeting’s outcome was successful, as Wyckoff was “rushing” home with Alliance Assurance’s proposal. It was later reported that he sailed on Titanic “merely in order to get home at the earliest possible moment.” To my mind, this apparent urgency places the date of the meeting with Alliance much closer to April 10, rather than the first week of April.

Returning to a docked ship for several days after the meeting would not be consistent with someone rushing home with a very important business proposal. Likewise, if the meeting were nearer to April 10, why would he have taken the very unusual step of sailing on Titanic’s delivery trip on April 2, especially since regular, reliable ferry service was available?

Alliance’s proposal was to be delivered to Williamsburg Fire’s board at a meeting scheduled for Thursday, April 18. Around the time board members had learned he had perished at sea, they received reminders of the meeting, signed by their late secretary. Clearly, Wyckoff fully intended to be present for the meeting. Titanic’s expected maiden voyage arrival at New York, late on April 16 or on April 17, would have provided the perfect timing for him to attend it.

Following Mackay-Bennett’s recovery of van der Hoef’s body from the sea, a well-attended funeral was held at his home at 109 Joralemon Street in Brooklyn. The newspaper report of the solemn event again noted he was “hurrying across the ocean” when his life was taken.

(Michael A. Findlay)

Conclusion

The reader must judge whether the story of Titanic’s alleged Belfast passenger should be consigned to the ever-growing list of disproven legends. When the miniscule evidence in favor of a Belfast departure is weighed objectively against the mountain of evidence (though often circumstantial) against it, one should at least view the story with a very hearty skepticism. While a definitive conclusion is likely impossible this far removed from April 1912, the author hopes this article will serve as a reference point for future incredulity.

Acknowledgements

Charles Haas is owed an exceptionally large portion of my gratitude. From the beginning, he thoroughly discussed with me the various minutiae of my theory, searched diligently for any pieces of new information, and kindly shared the files he and the late Jack Eaton had accumulated regarding van der Hoef. Thank you ever so much, my friend. Daniel Klistorner took the time to discuss van der Hoef’s booking and helped make comparisons of ticket prices of travelers in nearby cabins. His suggestions and input were invaluable. Mark Chirnside provided his objective thoughts on the likelihood of an ordinary passenger boarding Titanic at Belfast, for which I am grateful. George Behe combed his extensive files for any mention of this mysterious passenger. Michael Poirier was very encouraging throughout this entire endeavor, and he, Tad Fitch, and Bill Wormstedt were valuable beta readers.

Sources

Brooklyn Life, July 22, 1899, August 2, 1902, April 23, 1904, January 27, 1906, May 4, 1912

Belfast News-Letter, September 28, 1904, April 2, 1912, April 15, 1912, April 17, 1912

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 4, 1912, April 16, 1912, June 10, 1912

The New York Times, March 30, 1912.

The Sun, March 31, 1912.

Northern Whig, April 2, 1912.

Hampshire Independent, April 6, 1912.

The Standard Union, April 16, 1912.

Times Union, April 16, 1912, May 4, 1912

The Times, April 18, 1912.

The Huntington Press, May 7, 1912.

The Western Times, July 16, 1912.

Limitation of Liability Hearings Claim, Claim of Long Island Loan & Trust Company (Wyckoff Van Derhoef), December 6, 1912.

Registry of Shipping and Seamen: Agreements and Crew Lists, Series III: Titanic, BT 100/259 and 100/260, The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, England.

Eaton, John P., and Charles A. Haas. Titanic: Triumph and Tragedy. W.W. Norton & Company, 1995.

Eaton, John P., and Charles A. Haas. Titanic: A Journey through Time. W.W. Norton & Company, 1999.

This article was first published in Voyage 127, Official Journal of the Titanic International Society, Inc., Spring 2024.

Comment and discuss