(Courtesy of Senan Molony)

JOSEPH Cannon was a newly-qualified, newlywed wireless operator who found himself flung into the maelstrom of an extraordinary night at sea on his own maiden voyage in 1912.

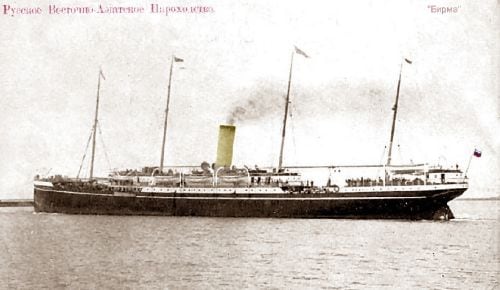

Cannon, a 24-year-old Londoner, had married his sweetheart, Isabel, just before taking up his first posting. He was going aboard ship for the first time, not as a Marconi man, but as a key-tapper for a rival firm, The United Wireless Company of America. And his first ship was to be the Birma, of 4,859 gross tons register.

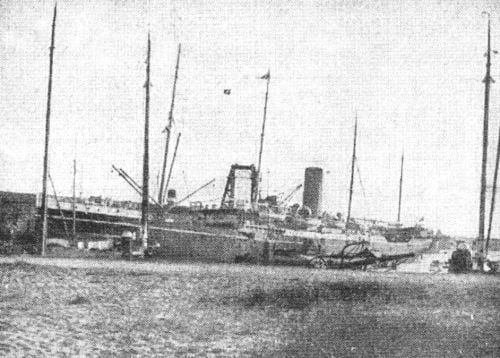

Aboard this Russian East Asiatic Company vessel, formerly the Arundel Castle, they used the De Forest wireless system, owned by United Wireless. The company was a bitter rival to Marconi, whose operators were expected to ignore De Forest transmissions and to offer no assistance to any ships so equipped.

Joining the Birma, Joseph Cannon thus entered both a cockpit of international competition and, by contrast, a world of multi-cultural cooperation within his own vessel, which served as a veritable melting pot of identities and tongues.

(© Daily Sketch, courtesy of Senan Molony)

By way of illustration, the fresh-faced Londoner was regarded by his new captain, Ludwig Stulping, not as a “Sparks,” but a “Funker” – from the German verb funken, to transmit. And it was Cannon’s job to transmit and receive in a couple of languages.

This is not as difficult as it may first appear. Messages would have been written in block capitals and easy to send out – since Morse code only translates the letters into dots and dashes. Any communications intended for the Birma would have been prefaced by her call sign of SBA, and similarly easy to recognise and note down.

Despite the white, red and blue ensign that flew at her stern, however, one language Cannon did not have to worry about was Russian, its Cyrillic script not catered for by classic Morse, which dealt only with the Western alphabet.

Aboard ship, Cannon joined the existing operator, an experienced hand named Thomas G. Ward. He was a fellow Britisher, from Southampton.

Cannon’s first leg of his maiden voyage was westbound to New York. The weather was atrocious, with huge grey swells and ripping whitecaps. The Birma shipped a lot of the unwanted Atlantic, scuppers spilling sweeps of seawater across the groaning decks. The young operator, hearing the banshee wails outside his shack, might have been forgiven for wondering what he had let himself in for.

Landfall in magical New York almost certainly helped him forget his nausea and any lingering nautical unpleasantness. A crick in the neck from craning upwards at the stretching skyscrapers is likely to have proved his only physical discomfort. He presumably managed to shop for a few pleasing trinkets for his sailor bride at home.

Captain Ludwig Stulping, born Liudvikas Stulpinas in Lithuania, is buried in Klaipeda (formerly Memel) on the Baltic coast of that country.

Courtesy © of Senan Molony

And then it was time for the return journey. Birma would be bound east for Rotterdam and thence to Libau, a Baltic seaport in modern-day Latvia, but in 1912 a vital entry point to Imperial Mother Russia.

It was, naturally, also an exit point – used by some 40,000 emigrants a year who hoped to find a better life in the United States of America.

The Birma stowed a general cargo, recoaled and embarked a relatively small number of paying passengers. The 390-ft four-master finally made motion away from the bright lights of the city and was soon thereafter sliding into the dropping dusk of the narrows. It was the afternoon of Thursday, April 11, 1912.

This was a departure almost simultaneous to that of the Titanic, by then leaving behind the last low smudges of Ireland on the other side of a great ocean. Both vessels, unbeknownst to each other, were embarking on a date with destiny.

It was a humdrum beginning. The Birma steamed a course due east. Cannon took the odd service message to First Officer Alfred Nielsen on the bridge, but there was little else for him to do. He would later write to his parents –

Dear Ma and Dad,

Just a line or two as I know you would be expecting to hear from me. We are at present in mid-Atlantic. Lovely sunny day, and fairly smooth. Indeed very diferent to our going out. I never saw such high seas. I thought you were joking when you told me about them. But this return journey is just the reverse, with the wind all behind us…

The wind would have firmly fleshed out the canvas of a sailing ship, but it had little effect on the Birma as she steamed along at her top service speed of thirteen knots. Thursday crept into Friday, the superstitious day for mariners – but all was well. Friday the 12th might have been considered a narrow calendrical shave, but then the 13th arrived, safely attached to Saturday.

All this time the Titanic had been doing most of the work to close the 3,000-mile gap between the pair. The ships were due to pass in the early hours of Monday, the White Star vessel on the more northerly track to New York, the Birma safely to the south, eastbound to Europe.

On Sunday evening, the Birma was approaching the significant mark of being 1,000 miles from New York. The calculations in the bridge, had they been taken then, would have shown 989 nautical miles elapsed by 11:45 p.m.

(Courtesy of www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/museum)

At that moment, ship’s time, Joseph Cannon was in the wireless shack, taking snippets of news from Cape Race for Monday’s on-board newspaper. He was about to be jolted by one of the greatest headlines in the history of mass communication.

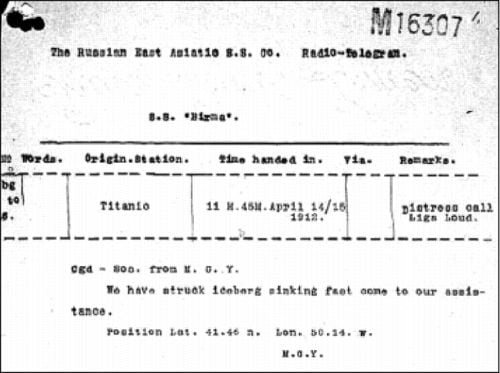

Identified by her code letters, MGY, a strange liner came crashing into Cannon’s headset. Using both old and new distress call letters of CQD and SOS, the communication ran: “CQD – SOS from M.G.Y.: We have struck iceberg sinking fast come to our assistance, Position Lat. 41° 46' N., Long. 50° 14' W. – MGY.”

Stunned, Cannon jotted down the position. In his letter to his parents he would later recall the latitude as 41° 44’ (not 41° 46’), but an official report from Captain Stulping to his owners made clear the Birma first heard the Titanic’s corrected SOS position of 41° 46’ N, 50° 14’ W. This was a location that would be shown to be hopelessly inaccurate 73 years later.

Cannon immediately woke his colleague. The more experienced Ward was likely the source of Birma’s reply to the stranger – “MGY, what is the matter with you? – SBA.” The ether buzzed back: “OK – We have struck iceberg and sinking, please tell Captain to come – MGY.”

The two telegraphists now rushed with these messages to the bridge, whereupon Captain Stulping took charge. He calculated Birma’s position as being between 106 and 107 nautical miles south-southwest of the vessel in distress, whose name he did not know. Cannon had flipped through the identification book, but Titanic was so new her call sign was not listed in the Birma’s pages.

Stulping and his officers calculated their course and swiftly turned their vessel on a heading of east-northeast, or 56.5 degrees by compass. The Master ordered an extra shift of fifteen stokers turned out, and all possible speed put on.

The Birma, identified by her own call-sign of SBA, was soon answering the stranger with the words: “We are 100 miles from you, steaming 14 knots, be with you by 6.30. Our position Lat 40° 48’ N, Long 52° 13’ W – SBA.”

“OK OM [old man] – MGY,” reported the Titanic’s chief wireless operator, Jack Phillips, having taken over the key from his junior colleague, Harold Bride. The laconic Phillips must have known that a 6:30 a.m. arrival constituted a useless offering.

(Cannon family, courtesy © of Senan Molony)

Copy wireless slips sent to the British Inquiry by the Russian East Asiatic Company and detailed in file M16307 in the British National Archives at Kew, show glimpses of how the disaster unfolded. One message declares: “SOS SOS CQD CQD – MGY. We are sinking fast. Passengers being put into boats. MGY.”

Hearing other vessels responding to the plaintive appeals, Birma suddenly thought to ask the Frankfurt who this mysterious MGY actually was. The North German Lloyd vessel replied: “MGY is the new White Star liner Titanic – Titanic – OM; DFT."

Time wore on, and with it, Titanic desperation: "SOS SOS CQD CQD - MGY. Sinking head down. 41° 46' N, 50° 14 W. Come soon as possible. MGY."

The hour-glass fatally emptied, and the last Titanic call noted by the Birma was a CQ to all stations - "Women and children in boats. Cannot last much longer - MGY.”

And she didn’t. Here also ends the sheaf of messages in file M16307 – yet the same enclosure also contains a useful two-page Official Report by Captain Stulping. He wrote that at 4 a.m. he called his entire crew out, “and we began to prepare everything necessary for the reception of the shipwrecked people.”

Stulping continued, “At 7.30 a.m. we arrived on the scene of the wreck [the empty SOS position]. There we saw some immense icebergs to the east, beginning from NE to S, and as far as the eye could reach there lay pack ice with icebergs, so that it was out of the question to proceed through the ice, and it was quite clear that the Titanic could not have been at that spot.”

The Birma knew the SOS location was in error, just as both Captain Moore of the Mount Temple and Captain Stanley Lord of the Californian would later convey the same to a stone-deaf British Inquiry, which chose instead to trust the Titanic’s distress position, even though the White Star liner could demonstrably not have reached that far west.

At about 1:40 a.m., Joseph Cannon, aboard the Birma, received this desperate message from Titanic.

(Courtesy of www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/museum)

Joseph Cannon continued his shipboard letter to his parents:

Of course you have heard of the loss of the Titanic? We went to her aid and was [sic] only 100 miles when I heard her distress call. She gave us her position at Lat 41° 44’ N, Long 50° 14’W. This was slightly wrong, and other ships also went to the same position as our boat. When I heard the distress call I was taking press news for the next day’s paper, and I gave the alarm and turned every man jack out.

The SOS position being “slightly wrong” was something of a kindness – it was actually thirteen nautical miles out in comparison to where the wreck lies today.

The Birma had to steam south around the icefield, then north to where she could eventually see vessels in the recovery vicinity. “We had to get around the icefield by devious courses,” Stulping wrote. “About 12.15 pm we met the ss Carpathia going at full speed to the west, and we exchanged flag signals with her.”

The near five-hour delay in encountering the Carpathia shows how difficult the situation was, and how inaccurate the distress position transmitted.

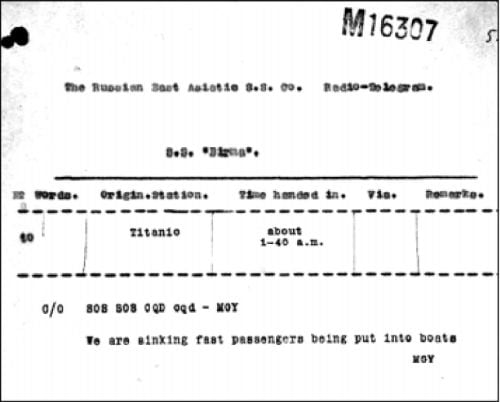

“I ordered the telegraphist to ask the Carpathia whether everybody was saved and whether we could assist in any way. The latter answered ‘stand by.’

“We were slow, and seeing that the Carpathia was continuing on her way to the west, I again ordered the enquiry to be made ‘Is there any use in our remaining to search further?’We received the reply ‘Shut up,’ as our wireless installation was of a different system from Marconi.

“Afterwards we received no news except that the Carpathia had picked up 20 boats with 675 passengers. Seeing that we could be of no assistance whatever, and being apprehensive of fog, which at this time of the year is very usual in this locality in the midst of ice, and judging it to be very risky to expose our own ship and passengers to danger, we went full speed and lay on our course to Rotterdam.”

But the Birma, rankling at her treatment, did not go straight to Rotterdam, instead making an unscheduled stop at Dover. Here she made her complaints to the press – a journalist aboard (Charles Edward Walters) having made special arrangement with the Daily Telegraph.

That the stop was planned is indicated by Joseph Cannon’s letter to his parents, which asked them specially to buy the Telegraph to watch out for mention of his ship. A full-page article duly appeared on April 25, 1912 (p. 16), with American writer Walters insisting that the Titanic’s position had been wrongly given in distress signals.

Amid such headlines as “Russians to the Rescue” and “Wrong Position Given,” Walters reported that the Birma found the SOS position on the western side of a great icefield, which he later said extended “between three and 12 miles wide, and 69 miles from north to south.” He would add, with deep significance, “but wreckage and lifeboats were several miles south-east on the far side of the icefield.”

The Daily Sketch followed up on the story the next day, putting an iceberg photograph by First Officer Nielsen on its front page. In a caption it added: “The Birma reached the position given them by the Titanic… it was then learned that the scene of the wreck was north [sic] of the floe, and the Birma steamed round to find the Carpathia taking on survivors.” Inside the newspaper repeated: “When, after daylight, they reached the position given them over the wireless, they found it was wrong.”

(Courtesy of Senan Molony)

The Sketch reported that the Birma officers and her two wireless operators had put their signatures to “a startling statement” that, when they had made offers to the Carpathia, including stores and provisions, the answer was “Shut up.”

It refers to receiving Titanic’s distress call, details the first position given, and says it was “slightly wrong. ” Other ships, he said, went to the same position. In fact, the Titanic wreck was found some 13 nautical miles to the east, and slightly south, of the ‘corrected ’ position given by Titanic in SOS transmissions.

(Courtesy of Senan Molony; now in private collection)

“The same signal came to us many times in the subsequent attempts to gain or give information. It is a known fact that the Marconi company will give no information to any ship not Marconi-manned, nor answer its calls, unless the ship is in distress. This may be a commercially fair system, but at the same time, while our ship was not in distress, we were trying to help.

“When it was found that our help was not needed, there came no word of thanks, no reply to our question as to whether more boats might be adrift, but only a salute from the flag at the stern of the Carpathia as she steamed on her way to the west.

“All day, and days following, we were refused any information. Every ship we spoke to replied. ‘Are you a Marconi ship? If not we have orders to give you no information.’ This after the energy of our officers and crew and the 30 hours’ vigil day and night to help!”

These complaints were studiously ignored by the British Inquiry, and only briefly examined at the U.S. Senate subcommittee hearings, when Chairman Senator William Alden Smith told John Bottomley, vice president and general manager of the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Co. of America that “a passenger on the Russian ship Birma, fitted with another wireless system, reported, on reaching London, that the ship’s offers to help care for the survivors on board the Carpathia were met by repeated signals to ‘Shut up.’ Were those answers in consonance with the general orders of the Marconi company?”

“Most certainly not,” Bottomley replied. “The absolute order is that everything must be communicated with, ships or anywhere, in any time of danger or distress. That is one of the first provisions of our general orders.”

The Birma’s revelation of relations between De Forest and Marconi operators may have obscured the point of her disclosure that the Titanic SOS position was wrong – a claim bolstered by a rude chart of the would-be rescuer’s course and the location of the icefield. This chart, prepared by Captain Stulping himself, was used as an illustration in both newspapers.

Its importance was ignored. Meanwhile, the British Inquiry was satisfying itself that the SOS position and the Californian’s claimed stop position that night could not both be correct, because rockets were seen by the Californian in the “wrong” direction.

Instead of correctly discarding the SOS position, as evidenced by the Birma map, the British Inquiry resolved the matter by concluding, in the teeth of the adduced evidence, that the Californian position was “not accurate.”

The discovery of the wreck in 1985 – with its obvious implications – led to pressure for a reappraisal of the evidence relating to the Californian. This was granted in 1990, and the publicity at the time drew forth the ghost of one Joseph Cannon!

The Daily Telegraph was also once more to the fore. On Monday, July 16, 1990, it reported that Joseph Cannon’s previously-unknown wireless log had come to light. Because it was a De Forest system, there was no trace of the Birma’s Procès-Verbal (PV) in the Marconi archives, unlike those of other ships that night.

The newspaper reported: “Mr. Cannon, a Londoner from Bowes Park, left his log to his son Louis, who died in 1978. It is now in the possession of his son’s widow, Mrs Molly Cannon..." [since deceased.]

This startling news received little attention at the time. It was however clipped by Rob Kamps of the Netherlands, who came across the article again in his records recently. It has since been verified on microfilm.

The Daily Telegraph reported that the log “includes three messages from the liner Californian, whose failure to go to the aid of the Titanic on April 14, 1912, is to be the subject of [a] re-examination ordered by Mr. [Cecil] Parkinson, Transport Secretary.”

It then recounted some of the messages already cited, but added Cannon’s personal notation: “Calling MGY at intervals. No reply after 2am... No further signals from MGY.”

The powerful evidence was yet to come, however. The Telegraph declared:

“One message supports the claim by the Californian’s Master, Captain Stanley Lord, that his ship, stopped in ice, was 19 miles from the Titanic when the liner hit an iceberg on her maiden voyage. The claim was rejected by the 1912 inquiry into the disaster.”

Journalist R. Barry O’Brien, modern-day inheritor of the tradition of Charles Edward Walters, then cited the crucial extract –

(© Daily Telegraph, 1990, courtesy of Senan Molony)

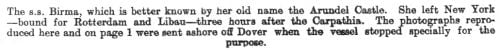

“The log records: 6.00. MWL [call-sign for the Californian] , proceeding for Boston, informs she is only 15 miles away from the position given by Titanic. Birma 22 miles.”

O’Brien immediately seized the importance of the entry: “The message supports Lord’s claim that his position when he stopped in ice at 10:20 p.m. on April 14 was 19 miles north by east from the position given by the Titanic in distress calls.

“With his engines stopped, he drifted some four miles closer during the night in a southward moving current.”

Irrespective of time differences between ships, the Birma’s logging of a 6 a.m. message from the Californian is absolutely vital to a debate about the latter’s distance from the Titanic that night.

The evidence from the White Star liner, including all her experienced surviving officers, had all been to the presence of another vessel within five miles of the sinking maiden voyager. Boxhall and Lightoller were convinced that the ship was “approaching” and “coming to our rescue.” The mystery ship later moved off, for she was not seen after daybreak at 4 a.m.

Captain Lord had always maintained that his ship was never underway, but stopped and drifting imperceptibly since 10:20 p.m. the previous evening. She did not approach anyone – and could not have been within five miles of the Titanic or the latter’s lookouts would have seen her.

Now Joseph Cannon’s mention of Californian being 15 miles away from the SOS position at 6 a.m. corroborates a separate report by the Virginian that the Californian reported herself 17 miles away as soon as she came on air and learned of the SOS.

Captain G. T. Gambell of the Allan liner Virginian told the British press on landfall in Liverpool that he, too, had been forced to steam from the west side of the icefield around to the east.

(Cannon family, courtesy © of Senan Molony)

He declared: “At 3:45 a.m. I was in touch by wireless with the Russian steamer Birma, and gave her the Titanic ’s position. She was then 55 miles from the Titanic and going to her assistance.

“At 5.45 a.m. I was in communication with the Californian, the Leyland liner. He was 17 miles north of the Titanic and had not heard anything of the disaster.”

The similarities of the Virginian disclosure to the Birma log kept by Cannon are profound in their importance. Together they show that the Californian wirelessed that she was a massive distance away – with at least two ships hearing and logging the assertion next morning.

[Birma's 14-knot speed and distance away cross-check with Virginian's two-hour timeframe. Virginian's report is in turn consistent with Birma's own.]

How did Cannon or Gambell know how far Californian was from the SOS position if they had not been told?

In a handwritten letter to the Board of Trade on August 10, 1912, Captain Lord had emphatically declared: “April 15th, about 5.30am, I gave my position to the Virginian before I heard where the Titanic sunk; that gave me 17 miles away. I understand the original Marconigrams were in court.”

(National Archives documents MT9/920E, M23448, Kew)

78 years after Titanic’s sinking, the Daily Telegraph ran this headline of July 16, 1990, with an accompanying article referring to its report of April 25, 1912 and going further to reveal the discovery of Birma’s hugely important wireless notes.

(© Daily Telegraph, courtesy of Senan Molony)

It now appears those messages were deliberately not opened by the Inquiry or scrutinized in their proper context. And nobody from the Birma or the Virginian was ever called to give evidence!

It is no good to suggest that 15 or 17 miles from the SOS position in the morning is irrelevant, since the SOS position itself was wrong. This is because the Titanic wreck indicates that the collision point, although much further to the east, was practically equidistant from the Californian’s claimed stopping place.

Obviously, the vast majority of that 15 or 17 miles distance must be to the north in any case, proving by nexus of the Birma and Virginian records that the Californian could not have been the mystery ship...

Fundamentally, it is established that the Californian didn’t move after encountering ice the previous night. Therefore, there is no logical way that those who narrowly describe themselves as "Anti-Lordites” can adapt the 15 or 17 miles.

Hitherto, without any corroboration, it has been easy to ignore the Virginian report. Cannon’s rediscovered log from his personal vigil aboard the Birma changes all of that.

Since huge distance was broadcast and verifiably heard, the best the critic will be able to manage is to suggest that Californian was lying at 5:45 or 6 a.m., which is very early for her to be lying. Yet her course thereafter is consistent with what she claimed.

Elsewhere, Joseph Cannon’s personal account relates:

“At 6 am came the first call from the Californian, followed by a CQ [all stations] call at 6.30 inquiring for news of the Titanic.”

Birma replied tersely: “No news.”

Pathetically, the Cannon log also contains a 7.45am entry: “Sight icebergs. Warn ships aft of us. Titanic believed to be in sight (prove to [be] icebergs instead).”

Too late for the Titanic in 1912, the Birma and Joseph Cannon now appear belatedly riding to the rescue of at least Captain Lord’s posthumous reputation.

(Cannon family courtesy © of Senan Molony)

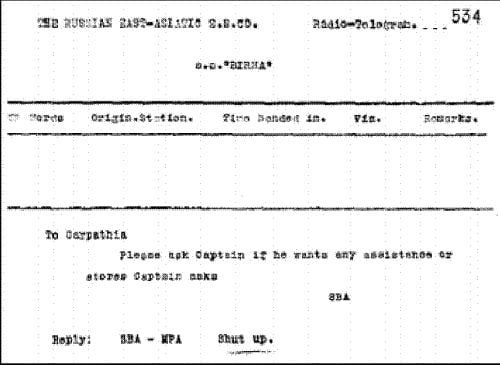

Cannon left the sea in the late 1920’s and later became one of the first cameramen for the BBC, based at Alexandra Palace. He continued his interest in radio and operated a short-wave transmitter at home. For long years into retirement, he remained a “ham,” keeping in touch with the many friends overseas who were similar radio enthusiasts – but who little dreamt of Joseph Cannon’s footnote role in the most famous maritime disaster of all time. He died in 1966.

The young operator’s letter to his parents sold at auction for a hammer price of £2,100 in September 2004 – and his personal log and other nautical papers, since passed to his granddaughter, now reside in a London bank vault. They include his version of events typed and signed on company notepaper as well as the original typed drafts of the report written by Charles Edward Walters for the Daily Telegraph.

The owner, a Mrs. S. W., who desires anonymity, confirms that the log is exactly as reported by the same newspaper in the extracts it quoted in 1990.

She also disclosed her plans in the future to send the cache to auction. This crucial material will then – however briefly – see the light of publicity once more.

See also : Daily Telegraph (22 April 1912) Russians to the Rescue - Icefield Described.

Senan Molony is author of Titanic and the Mystery Ship, published by Tempus Publishing Ltd. in 2006. Now in its third printing.

Comment and discuss