Those of you who have been members of The Encylopedia Titanica for any length of time or who have been frequent guests in the past will know that I have a bee in my bonnet about the popular interpretation of the actions taken by Titanic's First Officer William Murdoch in his desperate attempt to avoid that fateful ice berg.

You will all be familiar with the idea developed from the evidence of the stand-by Quarter Master Fred Olliver who, on day 7 of the US Inquiry told Senator Theodore Burton......

''I was stand-by to run messages, but what I knew about the helm is, hard aport. ''

In 1912 terms that meant that the rudder was turned hard over to the right.

However, QM Olliver never heard the very first helm order which was Hard-a starboard … hard left rudder. That was the one given by First Officer William Murdoch to Quarter Master Bob Hichens who was the helmsman at the time. It was an emergency action and meant to turn Titanic's bow away to the left from the iceberg right ahead. So what was that Hard-a-port second order all about? Who gave it? Why was it given?

The most popular interpretation is that Murdoch knew that when hard left rudder was applied, Titanic's bow would swing to the left, and her stern would swing in the opposite direction … to the right … toward the ice berg. This is absolutely true.

It is also absolutely true that Murdoch knew that if he immediately caused the opposite hard right rudder helm to be applied, Titanic's bow would stop turning left and start turning right and at that moment her stern would swing in the opposite direction, away from the iceberg. That too is absolutely true. However, there is only one thing wrong with this zig-zag -like manoeuvre and Murdoch was totally aware of it. He knew as did all senior Bridge Officers that for such a manoeuvre to be effective, it must be carried our with Titanic's engines running at Full Ahead on both main engines. That did not happen. According to the evidence, Murdoch rang down Stop and then Astern on both engines. Whether the Astern movement was full or half is academic as you will learn herein.

There are but two factors which totally negate any idea that Titanic performed the zig-zag-like turn so dear to so many hearts.

Reason Number One:

The engines and the ship were rapidly slowing down in the first 2 minutes. This from the British Merchant Seaman's Bible, Nicholls's Seamanship and Nautical Knowledge p.293:

''Extract from the Report to The British Committee (see White's Naval Architecture):

'It is found an invariable rule that during the interval in which a ship is stopping herself by the reversal of her screw,the rudder produces none of its usual effects to turn the ship......

It also appears from the trials that, owing to the feeble influence of the rudder over the ship during the interval in which she is stopping, she is at the mercy of any other influences that may act upon her.'

Reason Number Two:

From the evidence of Trimmer Tom Dillon who was in the main engine room during the entire sequence of engine movements we learn:

'' 3720. Was anything done to the engines? Did they stop or did they go on? A: - They stopped.

3721. Was that immediately after you felt the shock or some little time after? A: - About a minute and a half.

3722. Did they continue stopped or did they go on again after that? A: - They went slow astern.''

3723. How long were they stopped for before they began to go slow astern? A. - About half a minute.

The most important information from the above exchange is Dillon's last answer ''About half a minute''.

The reason for this is that at that moment, when the wing propellers started turning astern, they grabbed water from astern of the ship and threw it against the rear side of the rudder plate. How was the rudder turned at that very moment.. was it hard left or hard right?

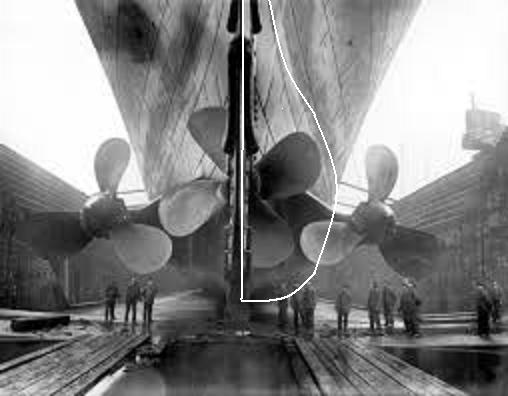

First let's go back to the very beginning; at the moment the last of the three warning bells from the lookout in the crow's nest is heard by William Murdoch on Titanic's bridge. I'll use my dreadful computer skills and a picture of Titanic's stern in drydock. Just pretend the wee men are not there. You'll have to use your imagination with the following pictures. I'll help where I can.

You are under water; Titanic is making 22.5 knots; the sea is rushing toward you out of the picture. You observe it travelling down the ships sides and being channeled into where the propellers are. When it reaches them, they grab it into their whirling blades, pulling the ship forward as they do. Then they discard it toward you in three great spirals. All this time, the rudder is end-on to you and more or less in the mid-ship position. You can't see its broad blade. The sea above you is smooth, there's no wind or current so the rudder's hardly needed to keep the ship going straight. Then all hell breaks loose!

Picture the scene on the bridge. First Officer Murdoch raises his night glasses at the sound of the last warning bell. He sees the iceberg ahead and orders hard-left rudder (hard-a-starboard in 1912 speak). You, from your vantage point see the great rudder swing to your left. (The white outline in the next picture represent this.) Now you are able to get a rear view of the rudder blade.

Immediately after he gives that first helm order, Murdoch, rings down STOP on the engine telegraph. Now you see the big propeller in the center come to a halt but both left and right propellers keep turning . Almost immediately after that, the side props begin to slow down quickly. Meanwhile, on the bridge, Murdoch's settling stomach rolls over once more. Hardly has 6th Officer Moody confirmed that the helm is hard-a-starboard when Titanic's starboard side contacts the ice. Murdoch knows that the possibility of the ship being wounded is very real so he immediately rings down ASTERN. He must stop her forward travel until a damage assessment can be carried out.

At this point let's pause and consider what you (if indeed you were in such an unenviable position) would have observed concerning the flow pattern of water round the rudder and propellers.

First, as the rudder blade is turned to the left hand side, it increasingly disrupts the flow and in doing so, is subjected to great, ever increasing pressure on its forward-facing surface. This has the effect of pushing Titanic's stern to the right and causes her bow to start turning left at an ever-increasing speed. Exactly as Murdoch intended.

Then the centre propeller comes to an abrupt halt. Suddenly, there is a very large obstruction to the smooth flow of water passing down Titanic on each side. This acts like a brake and immediately starts to slow the ship down. As she does so, the interrupted flow in the vicinity of the centre propeller is spilled left and right. The part of flow diverted left, interrupts the pressure on the rudder plate and reduces its turning efficiency. Titanic continues moving ahead but at an ever decreasing speed. Then the side propellers finally halt. Now there are three dragging propellers, acting much like brakes to the ship's forward progress and she slows down even more. By this time, the rudder is almost useless since what little remaining pressure on it's forward facing blade is being continuously disrupted by the distorted flow round the three stationary propellers

Thirty seconds after this, the side propellers begin turning in the opposite direction … slowly at first but at an ever increasing rate. The situation around the rudder and propeller now changes dramatically.

You're still underwater but now, the centre propeller is stopped and the wing propellers are turning in the opposite direction. They are dragging the water from behind you and throwing it forward. The left hand propeller is the most important one because the water it is pulling toward itself is being disrupted by the side of the rudder facing you.. the back of it. This means that there is now a pressure pushing the ship's stern to the left and her bow to the right. On the surface, it is causing the stern to swing away from danger to the right hand, starboard side. This effect will increase with the speed of the turning propeller. It will become very much more pronounced when the ship herself starts to move astern. The rudder has now lost all its ability to steer the ship in a forward direction.

William Murdoch was a very experienced Deck Officer. As such. he was well acquainted with the a ship's rudder action during twin screw operations. To my shame, I must admit to forgetting this fact when in the past, I have attempted to explain to others why he would never have dreamed of giving that second hard-a-port helm order so soon after the first, given the circumstances he found himself in. Like my nose, the answer was in front of me. But also like my nose, I just didn't see it.

The sticking point was explaining how it was that witnesses saw the ice berg astern and on the starboard quarter shortly after it passed Titanic's stern. How could such a situation arise without Murdoch performing a hard left then hard right zig-zag manoeuver?

Then it hit me. I went back to first principals; cast my mind back to the days when I had a twin screw vessel and was steering her in reverse. The answer was that Murdoch simply had to keep his helm hard over to the left and the pressure of the reversing port propeller on the rear face of the rudder would push the stern clear of the ice.

In this next picture, we consider what would have happened had Murdoch actually put the helm hard over to the right. You have to go back under water for this.

Now, the right hand wing propeller is the important one.

As it turns in reverse, it drags water forward against the rear of the rudder. This time, the pressure pushes the ship's stern to the right, toward any danger on that side (Such as an iceberg). At the same time, it causes the ship's bow to swing to the left, to the southward, not to the northward.

Would you or more to the point, would William Murdoch with his vast experience have even contemplated such a situation?

The foregoing exercise clearly illustrates that rather than attempt the popular idea of going hard left then hard right to avoid the ice berg, William Murdoch being the astute, skilled seaman that he was, knew perfectly well that there was absolutely not time for such a luxury. He there fore simply attempted to go to port round the iceberg and would have happily done so without touching his engines or varying his initial helm order. Unfortunately Titanic was too close to the danger and she contacted the berg. Murdoch thought she would not do so right up until the moment of impact. However he did know that the ice was too close for comfort so he rang down STOP to limit damage,if any, to his starboard propeller. He had to stop both engines because if he had stopped only the starboard one, the thrust of the port one would have seriously hampered the rudder effort to turn Titanic away to the left.

The second Titanic hit the ice, Murdoch knew he would have to stop her as quickly as possible. He also knew he had to shut all the water tight doors on the tank top deck. He would then have rung his engines astern. However he would also know that if he put the rudder hard right (hard-a-port) while the engines were running astern, he would cause the stern to swing back toward the ice-berg. He could not know how soon this would happen so he would not touch his rudder.

So when and why was the hard right ruder order given? The transcript of QM Olliver's statement says ''When it was way down stern''. ''Way down stern'' is not a seaman-like expression. Perhaps a typo here? Or a misunderstood expression. Whatever! He surely meant ''When it was way down astern''?

In the foregoing pages I have attempted to show why I do not believe that William Murdoch ordered that second helm order as part of the attempt to avoid the ice berg. However, if such an order was given, and there's no sensible reason to think otherwise, then it was given for specific purpose. It could not have been given after the engines started turning astern because that would have been counter-productive. It was not given before the engines were started astern for the same reason. Moreover it could not have been given in isolation when Titanic was stopped because a rudder does not work when a ship is stopped in such circumstances. It follows that it must have been given in conjunction with an engine order. But why would it have been given at all?

My best assessment is that it was given about 7 or 8 minutes after impact, when 2nd Officer Boxhall had returned from his first inspection visit and when QM Olliver had returned to the bridge after delivering an order from the Captain to the ship's Carpenter to sound the tanks. At that time, Boxhall had reported that he had not found sign of any damage. That would be the last calm moment in what remained of Captain Smith's life. At that moment , could indulge in annoyance at the fact that this thus far maiden voyage of Titanic had been marred by this bit of irritation. Consequently, he would be thinking about making up lost time. There wasn't much he could do about that except get ready to resume the voyage the moment he knew his ship was still safe and seaworthy. There was, however, one thing he could do. If at that moment, Titanic was not pointing toward New York then in anticipation of ringing down Full Away On Passage once more, he would make her ready. He would bring her head round and back onto her original course. As I have already pointed out, to use the rudder to turn the ship, he would have to start the engines on AHEAD. There would be but one caveat … he did not have the complete picture therefore he would not want to move from where he was until he did. This being so, any use of the engines would needs be short .. just enough to make use of the ruder then all head or stern-way would be stopped. I there fore think that Captain Smith asked the helmsman, QM Hichens how the ship was heading by compass. The QM's answer told Smith that he had to bring the ships bow round to the right. He would therefore go to the engine room telegraph and ring down STAND BY. At the same time he would turn to William Murdoch and quietly order: ''Helm hard a port Mr. Murdoch.‘

Murdoch would acknowledge and shout '' Hard-a-port''.

6th Officer Moody in the enclosed wheelhouse standing beside QM Hichens would repeat the order ''Hard-a-port''. Hichnes would spin the steering wheel to the right. When it was hard-over he would yell ''Helm's hard-a-port sir''. The order would be repeated loudly by Moody. Then and then only, would Smith ring down an AHEAD movement. The engineer on the control platform would acknowledge and feed steam to the main engines. At this moment, Murdoch would be at the door of the enclosed wheel house. Smith would tell him ''Let me know the minute her head starts moving Mr. Murdoch''. Moody would hear this and be looking over the shoulder of Hichens and watching for the very first sign of the steering compass starting to swing. When it did, he would advise Murdoch who in turn would tell Smith.

As soon as he got confirmation that the ship's bow had started to swing, Smith would ring down STOP. He would Tell Murdoch ''Steady her on 265 True Mr. Murdoch. Let me know when she's right-on''. Then he would go out onto the the bridge wing and look down to see if his ship had gained any headway. Obviously it did because he rang down SLOW ASTERN to stop her moving forward. As soon as he did so, he would look aft and watch the propeller wash round the stern. When he saw it creeping forward, he would order down STOP for the final time.

We can only guess at what happened next but it can be an educated guess.

Once Captain Smith was satisfied that his ship was completely stopped or almost so, he would turn toward the wheelhouse. He would be met by William Murdoch or Moody who would tell him that the silent shadowy figure standing nearby was the ship's Carpenter with a sounding report. Within seconds, Smith's stomach would, like his ship, start to sink.

Conclusion

From day one, I have never believed that Titanic performed a zig-zag avoiding manoeuvre. I believe that the foregoing explanation proves that it would have been a physical impossibility for her to have done so.

Conflicting Evidence.

I have had my say regarding this, but it is only fair that we should consider the evidence submitted by others as proof that William Murdoch did indeed attempt a zig-zag avoidance and that the hard-a-port helm order was give as part of it. Further more; that the consequence of this second order was that Titanic finally ended-up pointing North West when she stopped.

The principal witness used is Quarter Master George Rowe. I quote the transcript of his sworn testimony

QM Rowe: This from Day 15 of the British Wreck Commissioner's Inquiry

Quote:

17667. When you saw this light did you notice whether the head of the "Titanic" was altering either to port or starboard? A: - Yes.

17668. You did notice? A - - Yes.

17669. Was your vessel's head swinging at the time you saw this light of this other vessel? A: - I put it down that her stern was swinging.

17670. Which way was her stern swinging? A; - Practically dead south, I believe, then.

17671. Do you mean her head was facing south? A - No, her head was facing north. She was coming round to starboard.

End quote.

If we carefully analyse Rowe's evidence we immediately discover that he bases his opinion on the relative positions of Titanic's bow and the light. He is asked if Titanic's head was altering and he immediately replies ''YES''.

Every bridge Officer worth his or her salt and every first year Apprentice knows perfectly well that other than an electronic aid or without reference to a steering compass or a fixed mark, it is impossible to accurately to determine whether or not their ships heading is changing. The witness clearly indicates that he did not use any aid other than the relative bearing between Titanic's head and the changing position of the white light on the port bow. Proof of this comes in his answer to Q.17669... ''I put it down that her stern was swinging.''

Rowe was a Quarter Master; a man who used the compass every day in his work. He did not refer to a compass but simply 'put it down to', guesswork. Rowe was seeing a change in relative bearing. His simply assumed that the other vessel was stopped and Titanic's bow was swinging right relative to a stopped vessel.

However, according to the evidence of 4th Officer Boxhall, the vessel in question was moving. It approached Titanic then turned and sailed away. This last action is borne-out by very many witnesses who saw its white light disappear when they were in lifeboats and before Titanic finally sank.

Futhermore, had the vessel showing the white light been stationary as was the case with Californian, then she would still have been visible to those in lifeboats. She would still have been visible when Carpathia's lights were first seen but she vanished. Here's what Rowe had to say about the fate of the ship carrying that white light light: ''Toward daylight the wind sprung up and she sort of hauled off from us.''

If he and others had been seeing a light on a stationary vessel then that vessel would still have been there at daylight. No other vessel other than Carpathia was seen when daylight came. It could not have been, as has been proposed, Californian at a greater distance but appearing to be closer due to unusual atmospheric conditions. Simply because the conditions which would create such an illusion would still be present and the stationary Californian's superstructure would have been in plain sight.

The Labrador Current

There is another issue which requires airing here too.

Many of those who firmly believe that Chief Officer William Murdoch attempted a zig-zag manoeuvre and that Titanic finally ended-up heading North, also hold the very firm belief that the Labrador Current or such-like current was flowing southward at a rate of 1+ knots through the area at the time. Not one of them has been able to explain how an ever-slowing Titanic with an ineffective, almost useless rudder and stopped or stopping engines was able to overcome this strong surface current acting on her starboard bow and thus allow it to swing round to a North West heading. They are unable to do so because they have to chose between no Labrador Current or no zig zag manoeuvre. They cannot have both. As I have shown that can't have either and this raises another dilemma.

If Titanic was unable to turn through West and end-up heading North, the vessel seen on her port bow must have been to the westward of her and therefore could not have been the unfortunate Californian.

I'll now batten-down all hatches and wait for the inevitable storm of protest.

Captain Jim Currie.

January 21, 2015

Comment and discuss