Fortunino Matania (1881-1963) was, without doubt, the greatest of the Edwardian illustrators, in the long shadow of whom the likes of Arthur Rackham, George Armour, G. H. Davis, Cyrus Cuneo and H. M. Brock could only stand back in jaundiced awe and occasionally spiteful envy. Nobody could extol the virtues of the precise command of line, form and subject like Matania, who, by the time the Titanic sank on 15 April, 1912, had already been lauded for his treatments of such monumental contemporary subjects as the kopje of the Boer War. A favourite of King George V, Matania was the only artist given permission to document the King’s progress through India in 1911, and yet, for all his achievements up until the sinking, it would be his vivid renderings of the final hours of the Titanic that would forever seal his fame.

Fortunino Matania, The Sphere, 27 April, 1912

(Gouache on Board/Lithograph)

The two instantly recognizable paintings in question, entitled Women And Children First (appearing in the 4 May, 1912 edition of The Sphere) and the earlier Titanic Sinking (27 April) have long been familiar to Titanic scholars, enthusiasts and schoolchildren alike, indeed ever since Walter Lord’s illustrated edition of his bestseller A Night To Remember in 1976, Matania’s images have been perhaps most commonly reproduced in English books and articles describing the tragedy. However for their contemporary audience, these paintings were much more than merely descriptive impressions of the terrible event. Within a very short span of time they came to represent the embodiment of the sublime, a sentiment which, as Francis Spufford has demonstrated, was a sentiment peculiarly attuned to late Edwardian sensibilities,(1) and engendered a miniature cultural shockwave. No other artist came close to putting the contemporary Edwardian on the decks of the Titanic in quite the same way, and no other artist provided a commentary on the disaster so informed and level headed.

This essay investigates a duet of much less well known Matania ‘Titanic’ works, focusing on the brouhaha of the British Board of Trade Inquiry into the disaster, which convened for the first time at the Scottish Drill Hall, Buckingham Gate on Thursday, 2 May, 1912. As one might have expected for such a high profile occasion, a profusion of press photographers were present throughout the Inquiry to document the proceedings. Their photographs of the events inside and outside the drill hall, appearing daily in the National papers as the Inquiry got underway should perhaps have rendered the services of an artist like Matania null and void. Nevertheless, as chief illustrator for Britain’s leading picture weekly The Sphere, Matania was, as a matter of course, afforded easy access to the chambers where, beginning that same week, he began making preparatory sketches and selecting the appropriate vantage points for a series of illustrations that he intended should detail the key witnesses to appear before the Inquiry. There was great drama in the offing, as he well knew.

Though the British Board of Trade Inquiry was widely expected to be a more circumspect response to the disaster than the brash American Senatorial investigation then also sitting across the Atlantic, there could be no doubt that the British public were expecting fireworks. As the list of witnesses to be called was prepared prior to the opening of the Inquiry, Fortunino Matania was already making a bee-line around the figures he wanted to represent.

*

Robert Hichens, the surly young quartermaster who had been at the wheel of the great ship when she had struck the iceberg, was set to make an early appearance before the Board, fresh from his unexpected grilling before the U.S. Senate and would be a natural candidate for portraiture. There were plans too, to render the sensational appearance of Sir Cosmo Duff-Gordon (alongside his wife, Lucy, the only civilians called before the Board), who’s apparent ‘tipping’ of the men in Emergency Cutter No. 1, one of the first boats to be launched from the Titanic had been a mercenary incentive to persuade them not to row back for survivors. Finally, there was the chairman of the White Star Line himself, Joseph Bruce Ismay, whom Matania had met socially back in 1904; and whose name was now mud (or worse) in America, and in imminent danger of becoming so back home. Ismay’s appearance before the British Board of Trade would prove to be his last chance of redeeming himself amidst accusations of blackest treachery and yellow cowardice before the English gaze. All eyes would be on him…

Quartermaster Hichens took the stand at a little after 10:30 a.m. on day 3 of the Inquiry (Tuesday, 7 May, 1912) and was questioned initially by the Attorney General Sir Rufus Isaacs KC, followed, more hotly, by the Commissioner himself, Lord Mersey. On the face of it, he was a minor player in the story of the disaster; but several ugly traits of character revealed in America, had served to elevate him to dastardly importance as the British Inquiry began. Hichens of course, was the man savaged by a number of passengers from lifeboat No. 6, as a ruffian, heartless, and cowardly bully. Major A. G. Peuchen’s testimony regarding him before the U.S. Senate had started the ball rolling officially, with the Major claiming that the Titanic quartermaster had flatly refused to go back to pick up survivors struggling in the water, despite repeated calls to do so by the women in the boat, and an officers’ whistle beckoning him to do so from the decks of the sinking vessel. Speaking before the Senate Committee on Tuesday, 23 April, Peuchen made no effort to hide his contempt for the Englishman:

“No we are not going back to the boat.” He said, “It’s our lives now, not theirs” and he insisted upon us rowing further away… He was a very talkative man. He had been swearing a good deal, and was very disagreeable. I had had one row with him. I asked him to come and row, to assist us in rowing, and let some woman steer the boat, as it was a perfectly calm night… He refused to do it…(2)

Boat No. 6 was that in which Mrs. Margaret ‘Molly’ Brown had fashioned her own stalwart reputation. She claimed, with Hichens at the helm the women in the boat had had no choice but to row for themselves, the belligerent crewman offering no help at all, save to sit back, bewail and drink whiskey:

The man in the back of the boat, a quartermaster they said he was, told us to row away from the big steamer… began to complain we had no chance. There were only three men in the boat. We stood him patiently, and then after he had told us that we had no chance, told us many times, and after he had explained that we had no food, no water, and no compass I told him to be still or he would go overboard. Then he was quiet. I rowed because I would have frozen to death. I made them all row. It saved their lives.(3)

Naturally, Hichens had denied everything before the Senate, all but calling Major Peuchen a liar, and the rest of the women in ‘his’ lifeboat deranged. Questioned as to whether or not at one point, as had been suggested by a number of witnesses he had referred to the people plashing behind in the water as “stiffs” he refuted the claim; but hardly encouraged belief in his veracity by stating that he used “other words in preference to that”. This chip on shoulder attitude did not set him in good stead with Senator Smith, nor would it do so with Lord Mersey.

The questioning at the British Inquiry started off amicably enough. At the beginning Hichens was simply asked to tell the Board, in his own words, the sequence of events inside the wheelhouse on the night the Titanic struck the berg. Moving on to the evacuation in the lifeboats, Lord Mersey began to question Hichens much more closely. Certain statements the quartermaster began to make about the distances between his boat (No. 6) and the sinking Titanic did not square with testimony provided by other witnesses (including himself) before the Senate. Hichens continued to contradict himself and had begun to appear ever more shifty when the serious bombshells began to fall.

Question 1343, put by the Attorney General began:

Were you at the tiller through the night?

I was, all the night.

It was very cold?

Bitter cold.

Did you hear cries of distress?

Faintly; yes, Sir.For several minutes?

I could not say several minutes, for a minute or two.Did you answer to the question: "Did you hear cries of distress"? Answer, "Yes, for several minutes"?

I think I said for two or three minutes. I do not think I said for several minutes."Some men in the boat said they were the cries of people in the other boats signalling. I suppose they said that so as not to alarm the women." You said that?

Yes.Did you go in the direction of these cries of distress?

We had no compass in the boat and I did not know what direction to take. If I had a compass to know what course I could take from the ship, I should know what course to take, but I did not know what course to go upon.[The Commissioner] I do not understand you.

"I did not know where these cries came from."[The Attorney-General.] You heard cries of distress, you have told us?

Yes.Where did they come from?

I suppose from the "Titanic" when the "Titanic" had sunk.Could not you tell in what direction they were coming?

No, not hardly, Sir.Not hardly?

No, I could not tell what direction they were coming.[The Commissioner] Was this after the "Titanic" had gone down?

After the lights had gone. I did not know whether the "Titanic" was gone down, but the lights had gone away from the ship.[The Attorney-General] As I understand, what you told us before was that you saw the "Titanic," that she had her lights burning, you stopped about a mile’s distance, and when you got to about a mile’s distance you did not see the lights any more?

That is right, Sir.

That is what you tell us?

Yes.

What I want you to tell us is this: how long after that was it, or when was it, that you heard the cries of distress?

I had no time in the boat. I could not tell you hardly what time.Had you stopped before you heard the cries of distress?

Yes. We were made fast then to the other boat. Me and Bailey was made fast together.Mr. Bailey's boat?

Yes.

If I understand you correctly, you did not make any attempt to reach the cries of distress, did you?

It was a matter of impossibility; I could not do it.I want to understand why it was a matter of impossibility?

I only had one sailor in the boat, and I did not know where we were. I had no compass. I judge I was about a mile away the last time I saw the lights.[The Commissioner] You had your ears. Could not you hear where these cries came from?

Your Lordship, in the meantime, the boats were yelling one to another as well as showing their lights to try and let each other know whereabouts they were.I do not understand how a compass would help you to get to the cries?

That is the only thing that would help me, your Lordship.[The Commissioner] I should have thought your ears would help you better?

That final, barbed retort by Lord Mersey (unanswered by Hichens) made perfectly clear the Wreck Commissioner’s view of the quartermaster’s conduct on the night of the sinking. Not only was his seamanship seriously in question, but his truthfulness and duty to his fellow man were also under serious doubt.

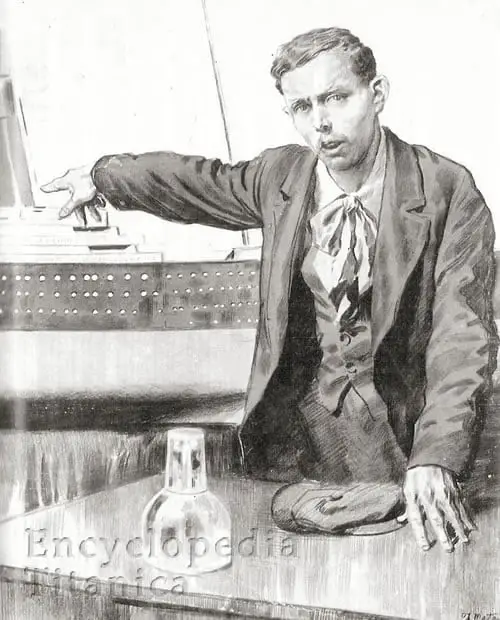

Fortunino Matania, The Sphere, 10 May, 1912

(Pen & Ink/Lithograph)

Of course, this was gold dust for an illustrator. Matania, present throughout the questioning, chose to show Hichens in demonstrative mood, staring almost angrily out at the viewer, as though challenging us to argue with his point of view, and gesticulating forcefully towards the shipmakers’ model of the Titanic in the background. He points over in the direction of the wheelhouse where he had been stationed on the night the ship sank, but though the question being put to him probably comes from the earlier part of the session, there is a clear sense of discomfort in his stature.

Under Matania’s scrutiny Hichens appears desperately unruly, his brows knit, jaw cocked, clothing unkempt (as one would expect) and in a model of pent up aggression, his cloth cap remains scrunched up tightly on the dais before him. There is palpable animosity in his gaze, highlighted by the artist’s glaringly sparse brushwork about the face, and in particular the deep chiaroscuro between forehead and cheekbone. The fingers of the witness’s left hand press firmly down on the dais, as though reaching out for the comfort of solidity, or holding back from involuntary clenching. One could almost call such a representation animalistic, as though the Titanic quartermaster were holed up in a cage, a specimen to be looked at, but not sympathized with.

*

It could be argued, as his monographer Percy Venner Bradshaw pointed out in 1918 (4) , that Matania’s unequalled reputation had already been assured before he tackled the fallout from what would become the most famous maritime disaster in history; but public (5) and professional reaction to his Titanic work was, nevertheless, unprecedented. After the sinking Matania’s studio apartment in London became the frequent haunt of painters such as John Singer Sargent and writers such as John Galsworthy and Ford Maddox Ford. His output, for many years, had been nothing short of staggering, completing an average of 800-1000 individual pieces a year, and in a bewildering variety of styles and media, sketches, drawings, watercolours, etchings, and paintings in tempera, oils, and gouache with the bare minimum of deadline time, a fact which made his reputation carry all before him; and yet even so prolific a painter as Matania had to pass on the baton sometimes.

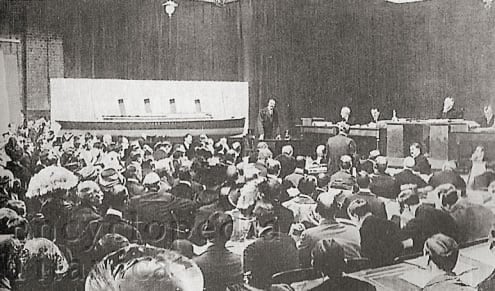

The artist had intended to detail Sir Cosmo Duff-Gordon’s much vaunted appearance before the Wreck Commissioner on 17-18 May himself, however, too busy with other matters to take part in the proceedings on those dates, this task was vouchsafed to a respected professional friend Balliol Salmon (1868-1953). Sir Cosmo Duff-Gordon At The British Wreck Commissioner’s Inquiry Into The Titanic Disaster eventually appeared on the front page of the May 25, 1912 edition of The Illustrated London News and was a model display of Salmon’s near photographic pictorial representation. But this was of course, not quite what Matania had had in mind. Any press photographer could have supplied much the same account of Sir Cosmo’s questioning as Salmon did. The whole point of singling out Sir Cosmo for special attention at the Inquiry was to draw attention to the scandal surrounding the former Olympic medallist’s seedy dealings in lifeboat No. 1. A close up portrayal of the effete knight of the realm, perhaps being directly challenged as to his conduct by Sir Rufus Issaacs, or indeed Lord Mersey himself, was just what was required to bring the story tantalisingly alive; but though he presented the figure of Sir Cosmo in much the same defiant pose (hands placed squarely on the dais in front of him), as Matania had presented Hichens, Salmon really paid scant attention to the finer details of the drama unfolded. Ultimately, the painting was far too static.

Balliol Salmon, Illustrated London News, 25 May, 1912

(Gouache)

And yet, the materials for something much more substantial had certainly been there, throughout Sir Cosmo’s evidence. It has often been claimed that Duff-Gordon was treated with kid gloves by the Inquiry, but closer readings of the transcripts, on the contrary, demonstrate a fierce determination on the part of the Attorney General to bring the celebrity husband to account. The 17th May proved to be Sir Cosmo’s baptism of fire. Sir Rufus, having gone through the preliminaries of the events onboard the Titanic on the evening of the disaster, got right down to issue of the unfilled lifeboats. Question 12533 began:

Did it occur to you that with the room in your boat, if you could get to these people you could save some?

It is difficult to say what occurred to me. Again, I was minding my wife, and we were rather in an abnormal condition, you know. There were many things to think about, but of course it quite well occurred to one that people in the water could be saved by a boat, yes.

And that there was room in your boat; that they could have got into your boat and been saved?

Yes, it is possible.And did you hear a suggestion made that you should go back, that your boat should go back to the place whence the cries came?

No, I did not.Do you mean that you never heard that at all?

I heard no suggestion of going back.Was any notice taken of those cries in your boat?

I think the men began to row away again immediately.Did they get any orders to do that?

That I could not say.That would seem rather strange, would it not?

No.[The Commissioner] To row away from the cries?

To row-I do not know which way they were rowing, but I think they began to row; in my opinion it was to stop the sound.[The Attorney-General] I think you said - correct it if you did not mean it - they were rowing away from the "Titanic" and then they rested, and then they rowed away some further distance?

They went on rowing, yes.And then I understand the "Titanic" went down, and I understand you to say they continued to row away. Do you mean by that they merely went on pulling?

They went on rowing.You do not know where?

I had been watching the "Titanic," of course, to the last moment, and after that, of course, one did not know where it had been.You do not mean to suggest they rowed back to the cries?

Oh no, I do not suggest that for a moment.

Sir Cosmo’s tacit avowal early on, that it would have been possible for lifeboat No. 1 to have gone back to pick up survivors was, unfortunately for him, rather glib; and his express inability to say for certain why in his opinion (cowardice? fear?) the crewmen did not at least attempt to go back, most surprising of all in a man with a clear conscience. Surely now the suggestion that he really had paid off the men was pushed a step closer toward truth. Always mindful of the fact that neither of the official inquiries were invoked with criminal proceedings in view of prosecution, and given the rigid Edwardian decorum of propriety, it was astonishing to find a man of Sir Cosmo’s standing facing such a charge, and in such a way. Edwardian notions of chivalry, and courage, were appalled; and it was for this very reason that Sir Rufus continued the attack. Significantly, it was not the crewmen in lifeboat No. 1 who were deemed culpable for not going back to pick up survivors; but Sir Cosmo, both as their social and (implied) moral superior. At the very least, the suggestion to go back, even if it had been refused, should have come from him:

We have heard from two Witnesses that a suggestion was made that your boat should go back to try to save some of the people?

Yes.You have been in Court when at least one of them said it. I am not sure whether you heard Hendrickson?

Yes.What do you say about that?

I can only say I did not hear any suggestion, that is all I can say.And you know it has been further said that one of the ladies, identified by the last Witness as your wife, was afraid to go back because she thought you would be swamped?

I heard that.And that, you see, was heard by a Witness who was sitting on the same thwart as you were?

Yes.Did you hear your wife say that?

No.Or any lady?

No.Or any person?

No.Do you mean that it might have happened but that you do not remember anything about it, or do you mean that it did not take place?

In my opinion it did not take place.Do you mean it is not true what the men are saying?

It comes to that, of course.

So, the crewmen were lying, for what reasons they knew best, and Sir Cosmo was innocent of any imputation. Sir Rufus, scenting blood, moved in for the kill:

You know that your boat would have carried a good many more?

Yes, I know that is so, but it is not a lifeboat, you must remember; there are no air-tanks.I must ask you about the money. Had you made any promise of a present to the men in the boat?

Yes, I did.Will you tell us about that?

I will. If I may, I will tell you what happened.Yes?

There was a man sitting next to me, and of course in the dark I could see nothing of him. I never did see him, and I do not know yet who he is. I suppose it would be some time when they rested on their oars, 20 minutes or half-an-hour after the "Titanic" had sunk, a man said to me, "I suppose you have lost everything" and I said "Of course." He says "But you can get some more," and I said "Yes." "Well," he said, "we have lost all our kit and the company won't give us any more, and what is more our pay stops from tonight. All they will do is to send us back to London." So I said to them: "You fellows need not worry about that; I will give you a fiver each to start a new kit." That is the whole of that £5 note story.That was in the boat?

In the boat. I said it to one of them and I do not know yet which.And when you got on the "Carpathia"?

When I got on the "Carpathia" there was a little hitch in getting one of the men up the ladder, and I saw Hendrickson. It was Hendrickson that I saw distinctly, when he brought my coat, which I had thrown in the bottom of the boat. He brought it up after me, and I asked him to get the men's names, and that list, in my belief, is his writing. It is merely a list of the names, and I think it is in Hendrickson's writing.Did you know either of the other two male passengers?

No, I did not know them, not till the next day.They were Americans?

Yes.Did you say anything to the Captain of the "Carpathia" of your intention to give that money to the men?

Yes; I went to see him one afternoon and told him I had promised the crew of my boat a £5 note each, and he said, "It is quite unnecessary." I laughed and said, "I promised it; so I have got to give it them."

But had he really to give it them? Searching questions would always remain attached to Sir Cosmo’s closing remarks on 17 May. For instance, why did he not, at any time, suggest going back himself? Why did he take it upon his shoulders to offer money to the men in his lifeboat out of bald compassion when he clearly did not feel the slightest ounce of that sentiment toward those other men, women and children struggling for survival? How was it possible for him not to know the name of the person he allegedly spoke to in the boat, when he remembered Hendrickson’s name so well afterwards? Such questions would never be properly answered. But in the end, Sir Rufus Isaaccs’ questioning could not have done more to guarantee Sir Duff-Gordon the carriage of an insidious stigma for the rest of his life if he had accused the man of being a cad to his face.

As already indicated, the Inquiry was not a criminal proceeding, therefore no charges of criminal behaviour were ever envisaged; and yet, through the sheer ambiguity of his own testimony Sir Cosmo’s moral conduct onboard lifeboat No.1, (and for that matter, his wife’s) were laid open for public, as well as private, censure. No-one, aside from the people onboard lifeboat No. 1 that night of course, could ever have known what really went on after its launch, but the dramatic withdrawal of the Duff-Gordon’s from polite social circles soon after the Inquiry’s end, or at least, polite society’s withdrawal from them, could not have been without the influence of Sir Rufus’ pointed badgering.

The appearance of the Duff-Gordon’s at the Wreck Commissioner’s Inquiry was almost a gala event attended by a number of ladies of fashion, Margot Asquith, the wife of the Prime Minister, and Miss Ismay, (J. Bruce Ismay’s sister), among them. From the vantage point chosen, Salmon’s painting was much more concerned with recording this element of the ‘money boat’ saga than anything else; one need only glance over the fine detailing of the many plumed and feathered formal hats present to understand the main, and instant appeal of the composition. From so far back, Salmon was assured of garnering the interest of the spectators themselves when the painting appeared in the press, many of whom (ladies presumably) would have readily been able to identify themselves and show all their widespread friends and acquaintances, when it was published. The grand sweep from left to right, of heads, all directed toward the diminutive figure of Sir Cosmo, moreover, at least gave a symbolic hint of the ‘court of opposition’ ranged against him, that Matania would have tackled head on.

*

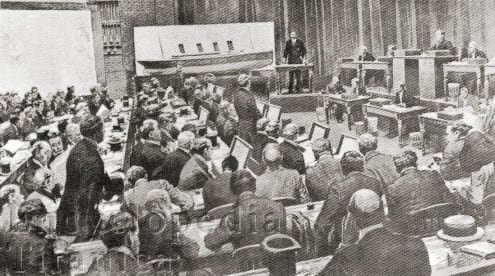

Though he may well have been privately disappointed at the finished result of Balliol Salmon’s approach to Sir Cosmo Duff-Gordon’s inquisition, Matania was intrigued enough by the painter’s compositional idea as a showpiece to develop it further, cheekily including a pen portrait of his artist friend (bottom left, ink brush in hand), sitting in much the same spot that he had been positioned during Sir Cosmo’s appearances. But despite the debt owed J. Bruce Ismay Before The British Titanic Inquiry must rank amongst Matania’s highest achievements, not just in terms of documentary prowess, but also in terms of optical verve and dynamism.

Fortunino Matania, The Sphere, 7 June, 1912

(Gouache on Board/Lithograph)

The contrast between his ‘courtroom’ and Salmon’s could not be any greater. Though both paintings take place in the same location, Matania’s appears far more electric in terms of figural movement and spatial interaction. In Matania’s work there is none of Salmon’s self-imposed regimen, here the figures are fully allowed to move, to lean, and to demonstrate.

An early criticism of the proceedings inside the Scottish Drill Hall was that the acoustics were all wrong for such an important Inquiry. Voices did not carry especially well, a point alluded to by Matania in the row of gentlemen journalists sitting (and standing) hands cupped to their ears in the foreground. They strain to hear the first question (18224), as the chairman of the White Star Line, perhaps the Inquiry’s most important witness, is addressed for the first time by the Attorney General (standing in the centre of the composition). One can almost feel the sense of hushed anticipation as the room falls silent and Sir Rufus Isaaccs begins, and, such was Matania’s pictorial skill, the audience can feel just as involved in the testimony as if they were actually present.

By the time J. Bruce Ismay appeared before the board on the afternoon of 4 June, 1912, he was already a vilified man. Understandably aloof, and still demonstrating the bluff shyness in public that had been a part of his character since childhood; this was a man entirely unsafe in the knowledge that popular consensus across the Atlantic held that he should not have survived. Feelings of guilt, remorse, and of course, a complete lack of public confidence in himself, and his beloved company, were all taking their toll. It is precisely this psychological impasse that Matania succeeds in eeking out. Refusing to commenting on his culpability or guiltlessless, the artist shows the awful nature of Ismay’s predicament with subtle force, deftly managing to present the chairman’s moral, physical, and social isolation.

In fact Ismay is shown at an even further remove than Salmon afforded the figure of Sir Cosmo, neatly providing a contrast between his thin frame, and the gigantic shipbuilders’ model of the Titanic off to his right. In fact, Ismay is dwarfed by the interior of the Scottish drill hall, in a way that reveals him, for all the monstrous faults attributed, to be a lone man after all. But presenting him as it were, ‘full length’ the artist not only draws attention to his exposure, but also, through a careful balancing of perspective, to ‘arrange’ the desks and the other people in the room into a kind of vortex around him. This was much the same kind of pictorial effect Salmon had been striving for in his painting of Sir Cosmo; but there, the vantage point had worked entirely against him. No such error of judgement undermined Matania’s attempt.

The viewer can readily imagine Ismay standing upon the precipice, through the tunnel of desks, cleat boards and men ranged near and far. At times, he certainly made for an uncomfortable witness. He was for instance, at a complete loss to explain why he, as an ordinary ‘passenger’ onboard the Titanic for her maiden voyage, should have been handed an iceberg warning by Captain Smith on the Sunday afternoon before the disaster:

Now on this day, on the 14th, did you get information from the Captain of ice reports?

The Captain handed me a Marconi message which he had received from the "Baltic" on the Sunday.He handed you the actual message as it was delivered to him from the "Baltic"?

Yes.Do you remember at what time it was?

I think it was just before lunch.On the Sunday?

Yes, on the Sunday.

The following lengthy exchange, between Sir Rufus and Lord Mersey, then followed whilst Ismay stood completely ignored, before the entire hall. One can readily adapt Matania’s image of the isolated Ismay to the scene

The Attorney-General: Your Lordship remembers the message from the "Baltic." I am going to hand up to you a little later a document which gives the messages in their proper order of dates, but this is the one I am referring to now -I will read it. It is sent at 11.52 a.m. to Captain Smith, "Titanic": "Have had moderate, variable winds and clear, fine weather since leaving. Greek steamer 'Athenai' reports passing icebergs and large quantity of field ice today in latitude 41.51 N., longitude 49.52 W." If your Lordship will take this list you will see how convenient it is (Handing up a copy.) We will have some more printed to hand up to the Assessors.

The Commissioner: Yes, it would be very convenient for all my colleagues to have a copy of this before them.

The Attorney-General: Yes; we have got them printed. Strictly speaking, of course, we shall have to prove these, and they will be proved. If your Lordship will look at page 2, or, perhaps, it would be better if you will look at page 1 first to see how this is compiled. First of all, you have the copies of messages received by the "Titanic" between midnight of the 11th April, 1912, up to the 14th of April, 10.25 New York time, when her distress signals were first received. That is what I said we would have done before we adjourned. If your Lordship will look at page 2 you will see the message of the "Baltic" in the middle. It is referred to as the message book No. 77. You see it is to "Captain Smith, 'Titanic.'" You have it, no doubt.

The Commissioner: Yes.

The Attorney-General: That is the one which contains a further reference after the figure which I just gave you, "Greek steamer 'Athenai' reports passing icebergs and large quantity of field ice today in latitude 41.51 N., longitude 49.52 W. Last night we spoke German Oil Tank 'Deutschland,' Stettin to Philadelphia. Not under control. Short of coal, latitude 40.42 N., longitude 55.11." Now if your Lordship would like to complete this whilst you have got it before you, you will find, if you turn to the bottom of page 4 of the same document, the answer, "Time received 12.55 p.m. To Commander of 'Baltic.' Thanks for your message and good wishes. Had fine weather since leaving -Smith." Your Lordship will recollect that both these messages are said to be New York time. According to the description we have got here of the message sent and the message received, that is according to the evidence you have already got from the Marconi Company, New York time.

The Commissioner: I have got it marked in my own note that the message was sent out by the "Baltic" at 3.19.

The Attorney-General: I think that is too late. You say, sent out by the "Baltic."

The Commissioner: Yes.

The Attorney-General: That would be too late; it must be rather before two, anything from one to before two.

The Commissioner: Two o'clock. Your opening was not quite in accordance with what we know today.

The Attorney-General: The statement in the affidavit, I agree, is not quite the same as we have now got it.

The Commissioner: There is a substantial difference.

The Attorney-General: Yes, we know the facts now.

The Commissioner: I rather gathered from the Solicitor-General's examination that the difference was of no consequence, but it seems to me to make a substantial difference. There was only one message from the "Baltic."

The Attorney-General: That is all as far as we know, and we have been examining into it because of what was said originally by the Captain of the "Baltic" upon affidavit, upon which the statement was made if your Lordship remembers.

The Commissioner: However, this is the printed message in this document.

The Attorney-General: Yes, that is quite right. I rather think my learned friend did say something with regard to it. He agreed that it made a difference, of course, because it did not agree with the statement in the affidavit, and we mentioned that we would enquire into it, and we have got it now. Of course, there is the message, and, as you will appreciate, we attribute very great importance to that particular message; we think it is of very great importance.

Having somewhat circuitously set the scene, Sir Rufus turned back to the ordinary passenger with a stunning volte face.

[The Attorney General] Now what I want to understand from you is this -that message was handed to you by Captain Smith, you say?

Yes.Handed to you because you were the managing director of the company?

I do not know; it was a matter of information.Information which he would not give to everybody, but which he gave to you. There is not the least doubt about it, is there?

No, I do not think so.He handed it to you, and you read it, I suppose?

Yes.Did he say anything to you about it?

Not a word.He merely handed it to you, and you put it in your pocket after you had read it?

Yes, I glanced at it very casually. I was on deck at the time.Had he handed any message to you before this one?

No.So that this was the first message he had handed to you on this voyage?

Yes.And when he handed this message to you, when the Captain of the ship came to you, the managing director, and put into your hands the Marconigram, it was for you to read?

Yes, and I read it.Because it was likely to be of some importance, was it not?

I have crossed with Captain Smith before, and he has handed me messages which have been of no importance at all.

This was fudging it a little, and Ismay knew it. The facile attempt to deny that the ice message handed to him by Captain Smith was nothing out of the ordinary, especially when no other messages or Marconigrams had been handed over during the rest of the maiden voyage, simply made no apparent sense. Sir Rufus challenged him again on the point a little later on:

Did you understand from that telegram that the ice which was reported was in your track?

I did not.Did you attribute any importance at all to the ice report?

I did not; no special importance at all.Why did you think the Captain handed you the Marconigram?

As a matter of information, I take it.Information of what?

About the contents of the message.The ice report?

About the contents of the message. He gave me the report of the ice and this steamer being short of coal.It conveyed to you at any rate that you were approaching within the region of ice, did it not?

Yes, certainly.

Finally came the admission that Ismay had been aware of ice in the region, and by inference, that Captain Smith had brought the matter to his especial attention. Certainly this obtuse round of questioning put the chairman of the White Star Line in a hard position. The initial statement that he was an ordinary passenger had held very little weight with anybody, right from the start; the issue was even less certain given the Captain’s apparently deferential handing over of the Baltic’s Marconigram to him, on that Sunday afternoon. The importance of the message, as the Attorney General had already pointed out, was that it’s distribution changed the entire nature of the Ismay’s perceived (if not actual) role onboard, blurring the lines of authority, and raising a number of further, worrying doubts, such as was the Titanic making a speed run, and, if so, was that under company orders?

*

Throughout the course of the Inquiry, day by day, week by week, press photographers from all the main British dailies and quite a number of weeklies were present, often in pouring rain of an inclement May, outside the drill hall ready to photograph the succession of experts and witnesses. A very great quantity of similarly contrived photographs and monotypes of events inside the drill hall were also produced, leading inevitably back to the intriguing question of what purpose Matania saw in documenting the Inquiry through his art? For Matania was practically the only skilled painter of the day who was convinced that certain elements of the Inquiry would bear a much closer scrutiny in the graphic form.

Balliol Salmon’s image of Sir Cosmo Duff-Gordon was a failure because the artist found no way allow his intended audience to connect with his subject, it was a resolutely uninformed and plain, though professional piece of illustration; Matania’s Inquiry images on the other hand, were models of visual rhetoric. In Matania’s work, English justice (in the form of the setting of the Inquiry itself) was seen to be in full flight; and English honour, so traduced in the U.S. tabloids, was seen to be upheld.

Matania’s treatments of both Robert Hichens and J. Bruce Ismay were far from being uncritical, but still, under his watchful eye, the individual personalities of both men, supposedly reigned in before the staid Inquiry, shone through. Hichens, a moody and sullen man at the best of times, in Matania’s hand, at least shows a kind of fiery spirit, under duress, that was sorely lacking in lifeboat No. 6. Ismay by contrast, is shown as an elusive, and shy figure, neither condemned, nor exonerated, but certainly in the thick of it. Both character traits were considered curiously English, and it is here that we hit upon the subtext. Crucially, both of Matania’s Inquiry paintings anticipate any negative responses to the conclusions of the British Wreck Commissioner’s Inquiry by showing the processes of inquisition regularly at work; for after all, what could be more English than the notion of habeas corpus?

Notes

- See: Spufford, Francis, I May Be Gone Some Time -Ice And The English Imagination (London, Faber & Faber, 2003) pp. 7-14.

- Kuntz, Tom (ed) The Titanic Disaster Hearings: The Official Transcripts Of The 1912 Senate Investigation Day Four, Testimony Of Maj. A. G. Peuchen, Tuesday 23 April, 1912, p.199

- New York Times, Saturday 20 April, 1912

- Bradshaw, Percy V., The Art Of The Illustrator (London, Press Art School, 1918)

- For more on the public reaction to Matania’s Titanic imagery see the author's forthcoming PhD thesis Titanic: Art Into Myth - The Art History of an Unnatural Disaster 1868-1912 (Liverpool, John Moore’s University, 2006) Chapter 4.

Also Available: Anatomy of a Boat Deck Portrait by Senan Molony.

Comment and discuss