HERBERT Pitman appeared to lose confidence following the shattering experience through which he passed in April 1912.

HERBERT Pitman appeared to lose confidence following the shattering experience through which he passed in April 1912.

Anyone might.

The Titanic's Third Officer broke down while giving evidence in America at the point when he was asked about the piteous noises made by those drowning in the water.

"Crying, shouting, moaning," he vividly remembered. But his leadership position had shown him an obvious duty. He ordered his lifeboat back to the vicinity.

|

Senator Smith: You were in command. They ought to have obeyed your orders? Pitman: So they did. Smith: They did not, if you told them to pull toward the ship. Pitman: They commenced pulling toward the ship, and the passengers in my boat said it was a mad idea on my part to pull back to the ship, because if I did, we should be swamped..." |

Pitman, in command, with braid on his sleeve, allowed himself to be overruled by a group of complaining civilians.

He ordered his men to abandon the attempt. They pulled in the oars and lay quiet, listening for an hour to the myriads who were thrashing in their final throes or silently succumbing nearby.

In Pitman's case, the survivor guilt must therefore have been especially overpowering.

Whenever he recovered from the most immediate trauma to think about going back to sea, it seems that part of his self-adopted therapy was to aim to be the best officer he could in the years thereafter

But his own private iceberg lay in waiting, with the same invisibility.

It would destroy his deck career forever

Not just Pitman, but the Board of Trade had been encouraged to smarten up credentials in the wake of the Titanic disaster.

As it happened, a new report was just in from a committee which had been deliberating on a single aspect of marine safety. This time the Board of Trade would not hesitate about implementing its recommendations, as it had fatally deferred lifeboat recommendations in 1911. The Board now speedily adopted the toughest standards possible.

Herbert Pitman, preparing to subject himself to what would otherwise have been a routine re-examination in September 1912, was about to collide with personal and professional misfortune.

He would fall victim to a Titanic syndrome which, it might be argued, was all about giving the Board of Trade a double-bottom against future mishap.

On June 24, 1912, a report was issued by the committee appointed the previous year "to enquire what degree of colour blindness or defect of form vision in persons holding responsible positions at sea causes them to be incompetent to discharge their duties."

It had also been charged with advising whether any alterations were desirable in the BoT sight tests then in force for persons serving or intending to serve in the Merchant Service.

|

|

Captain Norman Craig, MP.

|

The committee found no evidence of casualties arising from defective vision, nor even a trustworthy estimate of the collisions and strandings caused by bad lookout. But it became seized with the evidence of two colour-blind gentlemen - one an unnamed Royal Navy officer, and the other the yachtsman Captain Norman Craig, MP. Craig had originally been booked on the Titanic but cancelled because of parliamentary business.

The product of examining these two gentlemen demonstrated "how great is the difficulty which colour blindness causes persons who have to draw inferences from the colours of lights at sea."

Experiments carried out by the committee at Shoeburyness, along the Maplin Sand, showed that such defective vision "may render a man incapable of distinguishing the colour of a ship’s lights, this effect being most marked at the greater distances, that is, 2,000 and 3,000 yards."

The two mariners "made 30pc mistakes in the lights shown to them at a distance of 2,000 yards."

Shocked at these findings, the Board of Trade committee recommended outright war on colour blindness.

And despite the fact that the committee recorded that it "cannot say definitely what degree of colour defect is compatible with the granting or retention of a certificate," it proposed a series of recommendations which "will make it much more difficult in future for a person with dangerous colour defect ever to pass the test."

The above paragraph shows the inherent weakness of adopting such a stringent rule - the committee had no idea what level of colour blindness was tolerable, yet it was determined to adopt an absolutist approach. It would probably have been surprised to discover that colour blindness, in varying degree, affects one man in twenty.

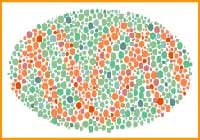

Are You Colour Blind?

If you cannot see a swirl of orange dots crossing this image you may have a form of colour blindness.

Link : Explanation and examples

Herbert Pitman was mildly colour-blind.

Pitman was aged only 34 in 1912, a young man who had been at sea precisely half his life.

He could not have operated as a deck officer if he was severely colour blind, since in its extremity the condition means being unable to tell red from green.

This is an obviously important matter, as a ship's port light is red, and her starboard light green.

An inability to distinguish between them could stand the observer vessel into grave danger of collision.

Ships are supposed to pass red-to-red (keeping to starboard) under the rules of the road.

Mistaking another ship's red light as a green one (on indeed vice versa) could mean a failure to discern a vessel as oncoming until it is too late.

Long experience compensates considerably for a certain decline in physical fitness due to age, but the Board of Trade promulgated in July 1912 that "no person who is liable to fail to detect the presence or to confuse the colours of average ships‘ sidelights at a distance of one mile is competent to discharge the duties of an Officer of the Watch."

It added in a Titanic-influenced note that it "would not be safe to depend on binoculars to compensate for defective sight."

Into this gathering nightmare walked Pitman, who had been four years as an apprentice with James Nourse Ltd., three years as an officer in the same employ; a year in the Blue Anchor Line running to Australia, six months in the Shire Line sailing to Japan, and five years with White Star.

Into this gathering nightmare walked Pitman, who had been four years as an apprentice with James Nourse Ltd., three years as an officer in the same employ; a year in the Blue Anchor Line running to Australia, six months in the Shire Line sailing to Japan, and five years with White Star.

Pitman, the soon-to-be-judged Incompetent.

Pitman who had passed the existing eyesight test seven times during his past career.

Ah, the old days. In the old days it was a matter of paying a fee of one shilling, to be examined by a superintendent who would promptly issue a certificate.

Masters and officers were encouraged by their shipping lines to periodically obtain the certs.

Yet in the anomalous days before the Titanic disaster, lookouts were not obliged by law to pass any eyesight tests at all.

For them it was purely voluntary. In the crow's nest of the Titanic, Fred Fleet had not been tested since 1907, and Reg Lee not since his army days in 1900.*

Alfred Young, Professional Member of the Board of Trade, explained to the British Inquiry why different standards could apply:

"The man on the look-out has to report a light, and the officer decides himself as to whether that is a red or green light. That is one of the reasons why a seaman need not be subjected to precisely the same test as an officer."

It is difficult not to see the above extract as anything other than class-ridden addle-headedness. As it stood, a lookout could not call out exactly what he saw - a red light, for example - but only a light. In the days before the Titanic sank, it could very well be that a colour-blind officer would decide on the fundamental matter of whether a light was red or green. The implications of what was cheerfully disclosed to Lord Mersey are staggering in retrospect.

It is also not difficult to see that the eyesight testing regime was itself utterly defective. Yet it also bordered on the laughable.

Before the 1912 committee report, officers had a colour test that could only weed out the most extreme forms of colour blindness. It was a literal form of woolly thinking, because it involved bits of wool... with candidates picking out from a bunch of ten different coloured wools the samples they thought best matched a test skein. Picking up wispy blobs in the brightness of a morning surgery obviously different greatly from appraising lights in the pitch black of the Atlantic.

Amazingly, the Board of Trade now kept the wool test (eventually scrapped in WW1) and supplemented this sheepishness with a lantern test - for use, not in daylight, but in simulated night conditions. That meant a darkened room.

The Board adopted the committee's design of a lantern with two apertures, showing light through twelve glasses - four reds, four greens, and four whites - which could be arranged in various combinations.

The new standard was "recommended" to the main shipping lines with advice that it would be enforced from January 1914. It also required "nearly normal visual acuteness" and a separate testing of each eye in relation to form vision. This meant the standard Snellen's board, being lines of diminishing-size letters familiar from stereotype.

Alarm quickly spread through shipping circles at these new requirements.

The Chamber of Shipping and the Liverpool Steamship Owners Association unanimously declared that the old standards had been high enough, and warned that the Board should not rush into tougher rules without adequate forethought.

The Board tartly responded that "in the case of the latter Association, out of a gross tonnage of nearly four millions controlled by members, one and a half million tons are owned by firms who prove by their actions that they do not regard the Board of Trade tests as wholly adequate to secure the efficiency of their own officers. These firms either enforce a higher standard than that hitherto enforced by the Board, or adopt the precaution of periodically examining the vision of their officers."

It added pointedly: "At an inquiry at a shipping casualty, witnesses as to lights and signals should always be tested for colour and form vision. Any officer should be held to be incompetent if his visual acuteness in the better eye has fallen to half-normal."

But the anger and controversy would not die, as the following attests:

SIGHT TESTS FOR SEAMEN

To the Editor of The Times

Sir -

One of the saddest instances of my career is when I have to give a verdict that one of our Mercantile Marne officers, who has been many years at sea, is colour blind.

He may have passed the Board of Trade test for colour vision many times, and then fails and is brought to me. I recently examined a man who had been rejected by the Board of Trade but who had previously passed the same test three times. As this was a test of congenital colour blindness, if he had been examined as to his ability to test coloured lights, he would have been detected in the first instance.

When I examined him with the new Board of Trade wool tests, in the presence of Mr A. W. Porter, he passed it with the greatest ease and accuracy. I would not have suspected that he was colour blind. When, however, he was examined with my lantern, he called green red and white green, and it is quite obvious that he would have been very dangerous in command of a vessel.

The Board of Trade tests also reject many normal sighted persons, and those with slight and unimportant defects of colour perception.

The Board of Trade form vision tests are also of the most primitive description. It should be noted that no medical man is employed as an examiner, and on appeal, a physicist examines the case. The Admiralty use the most efficient methods of testing their officers, and it seems extraordinary that the Board of Trade, at the chief centre of examination in the largest city in the world, should employ methods which would be rejected by a medical man in a small village.

A thorough inquiry into the methods of the Board of Trade is needed in the interests of the Mercantile Marine and of the nation.

Faithfully yours,

F. W. L. Edridge-Green

London, February 15th.

(The Times, Thursday March 6, 1913, p.18)

More and more spirited letters poured in, including this one:

SIGHT TESTS FOR THE MERCANTILE MARINE

To the Editor of The Times

Sir -

You have very kindly inserted several letters for me on the above subject. Will you kindly give your readers the benefit of the following case, which admirably illustrates our contention that incalculable harm is going to be quite unnecessarily inflicted in the direction of depleting the ranks of Mercantile Marine officers, unless the new Form Vision tests are repealed?

I repeat - what the late Sir Walter Howell himself admitted - that no single accident can be traced to faulty form vision on the part of an officer.

The case is as follows: - An officer in the Allan Line has been failed in the new Board of Trade eyesight tests, and has had to accept an assistant pursership in that company. The said officer was admirably qualified in every other way, and his experience of a since-school lifetime has, at one blow, been rendered useless, all through the unjustifiable and unnecessary excess requirement of the eye-testing department.

His case will be the case of hundreds, and scores of steamers will be laid up through a shortage of officers unless the Board of Trade realise their awful mistake. That eventually they will do is certain; why not pocket pride and do so at once, and so earn a meed of praise from the ship owner?

Yours etc,

John Glynn,

14 Chapel Street, Liverpool. May 1st.

(The Times, Wednesday May 7, 1913. p. 24)

It is noteworthy that Glynn, a shipowner, believed that the new eyesight tests would cause "scores of steamers" to be laid up for want of officers. This surely would be The Iceberg's greatest triumph - not only to have sunk the Titanic, but to have prevented dozens of vessels from ever going to sea at all.

And then came Pitman, for the iceberg had done for him too -

MERCANTILE MARINE SIGHT TESTS

The Case of an Officer of the Titanic

To the Editor of The Times

Sir -

With regard to the cruel case of an Allan Line officer, who was one of the victims of the Board of Trade sight tests, which is furnished in your columns by that well-known ship owner Mr John Glynn, allow me to put a parallel case, that of the surviving Third Officer of the Titanic, one of the finest specimens of British Mercantile Marine officer that I have come across - and I know many.

Prior to going to see 17 years ago he passed the Board of Trade sight tests. But he took the precaution of guaranteeing as far as possible his safety in this respect for the professional career upon which he was embarking. During his career he has passed the Board of Trade sight tests in both colour and form vision seven times.

Since the loss of the Titanic he presented himself for a further test under the then prevailing instructions of the White Star Line that their Captains and Officers should go through these tests periodically. He was then failed, and has now been invited by the Board of Trade voluntarily to surrender his certificate.

We have at present in hand 26 cases of our members similar to this, where fine young officers have been robbed of their livelihoods. The ex-Third Officer of the Titanic was, I should say, most sympathetically treated by the White Star Line, who have now appointed him as an assistant purser on one of their biggest vessels.

These eyesight tests are impractical and unfair, and a gross imposition on a most worthy class of the community. Furthermore, they are of great national moment in diminishing the supply of officers of the Merchant Service.

May I venture to hope that, with the publicity you have so kindly ventured to give to this matter, we shall soon see the Board of Trade substantially modifying their present attitude - that is, by throwing off the present tests as hopeless and unjust, and adopting some reasonable and practical tests in accordance with actual seafaring conditions.

I am, Sir, your obedient servant,

T. W. Moores

Secretary, the Imperial Merchant Service Guild,

Lord Street, Liverpool.

(The Times, Tuesday May 13, 1913. p.3)

The only mainstream Titanic publication to mention Pitman's subsequent career is Don Lynch's Illustrated History. It seems to imply that retirement to the job of purser came gradually for the Third Officer:

"Herbert Pitman remained at sea for thirty-five more years, although failing vision forced him to leave the bridge and join the purser's staff. For a period he even found himself serving aboard the Olympic. A widower, he retired to the town of Pitcombe, England, where he lived with a niece until his death in December 1961."

The point is that Pitman's eyesight did not slowly fail until he voluntarily reconciled himself to a less stressful occupation. Within months of the Titanic disaster he had seen his certificate ordered surrendered by the Board of Trade when his eyesight was just as good as it had always been.

It seemed the Pitman case may have sparked a small rebellion among officers at White Star, because the company announced pay and watch improvements in April 1913, and also that:

"The officers will not, as hitherto, be required to undergo the sight tests at the Board of Trade, but will be examined by the company's own doctor."

It was too late for Pitman, as it was in May 1915, when the rules for eyesight and teeth were relaxed by the Admiralty and Board of Trade simultaneously in light of the exigencies of national survival.

"Candidates who have been rejected for bad teeth or defective vision may present themselves again," declared the Board of Trade nobly.

Wisely, it never reimposed the same standards on the cessation of hostilities.

But perhaps some would see a rough justice in the case of Herbert Pitman.

The officer who had taken his cue from passengers in April 1912 remained taking orders from passengers for the rest of his career.

[For more on the lookouts' eyesight, see http://www.encyclopedia-titanica.org/discus/messages/5914/5022.html]

© Senan Molony 2004

All images courtesy of the author

Comment and discuss