Richard Frazar White entered Bowdoin in the fall of 1908. he was a graduate of Cambridge Latin School, and he had deep family ties to Bowdoin. All the men on his mother’s side of the family had attended the college, including his uncles; his cousins; his grandfather, William Adolphus Wheeler; and even his great-grandfather, Amos Dean Wheeler, who received a doctorate of divinity in 1860.

Richard Frazar White entered Bowdoin in the fall of 1908. he was a graduate of Cambridge Latin School, and he had deep family ties to Bowdoin. All the men on his mother’s side of the family had attended the college, including his uncles; his cousins; his grandfather, William Adolphus Wheeler; and even his great-grandfather, Amos Dean Wheeler, who received a doctorate of divinity in 1860.

While the other young men at Bowdoin may have struggled with homesickness at times, Richard had no cause to—his family moved from their home in Massachusetts to Brunswick before Richard matriculated. They lived in a stately home on the edge of campus called The Pines. located on the corner of Longfellow Avenue where the Brunswick Apartments are today, the elegant home was built as a summer place. It became the Whites’ full time residence when Richard began at Bowdoin. The Pines was decorated with Hawaiian motifs (the family had spent more than a year living in Hawaii) and artwork that Richard’s father had collected from all over the world.

Richard was a kind young man and a trustworthy friend who was an accomplished mandolin player. he loved nature and canoed and camped frequently. he also played golf, sometimes walking the links with President William DeWitt Hyde. Richard’s social time was spent with his fraternity brothers at Delta Kappa Epsilon. He was also a budding author and a member of the Quill’s editorial board, known for penning graceful verses and prose. ironically, one of his compositions was the diary of a sea voyage. Most notably, Richard was an excellent student, ranking at the top of his class junior year, and he was elected to Phi Beta Kappa. He endured a bit of good-natured ribbing from his friends about his intelligence. In the Bowdoin Bugle they teased that he would rather say “infinitesimal particles of saline humective fluidity” than “little drops of water.”

Richard finished his coursework in February of 1912, several months before graduation. To mark the occasion, Richard’s father arranged a celebratory excursion abroad to Europe. After landing in Southampton, England, they would remain for eleven days. The return trip was carefully scheduled so they would return stateside in mid-April, home in plenty of time for Richard to march with his friends at Bowdoin’s commencement.

Richard and Percival White made the Atlantic crossing aboard the RMS Olympic, a White Star Line luxury ocean liner. it was a pleasant journey, and they looked forward to their return on the Olympic’s new sister ship, Titanic. The “unsinkable” ship was to make its maiden voyage in April.

Since Richard’s father made it a habit to “collect” maiden voyages, a return trip on Titanic would have been a well-planned event. Back at home in Brunswick, Edith White was anticipating the first birthday of her granddaughter Matilda, who had recently come to live with the family. Edith had received a letter from Richard and Percival. Included in the letter would have been plans for the return trip. Beginning on April 15, reports of a maritime disaster in the North Atlantic began to circulate. The Titanic had hit an iceberg. Local Maine newspapers had little news, but Boston’s Christian Science Monitor reported that the ship had only been disabled. The passengers were safe and had been rescued by nearby vessels. The story was followed the next day by a conflicting Boston Globe headline : “Titanic Sinks, 1500 Die…Survivors Mostly Women and children.” Edith immediately traveled to Boston for the most recent news of the disaster. Richard’s elder brother, named Percival after his father, and her husband’s brothers joined the vigil. They joined the throngs outside telegraph stations and newspapers anxious for news. Edith phoned the offices of the Boston Evening Transcript, which had nothing to report. The Brunswick Record seemed convinced that the men were safe and “both are believed to be in New York at the present time.” The Worcester Evening Post had similarly good news: “Percival White. . .escaped according to word received by his brother.”

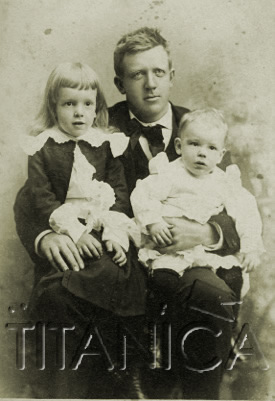

Percival White, and with his two children Percival Junior and Richard Frazar White

By April 16, the nation knew the Titanic was on the bottom of the Atlantic. According to the New York Times, hundreds survived, but they were out of range. When the ship arrived in New York harbor on April 18, it was clear that most of the Carpathia’s passengers were indeed women and children. Back in Brunswick, Edith’s housekeeper Anna Coffin grimly greeted friends and Bowdoin faculty, all deeply worried. She also told a reporter for the Berwick Record that she had had no word of the fate of the men. In New York, the Carpathia’s passengers began to tell their stories. The Boston Globe reported that the ship sank silently, but “the survivors cannot forget the cry of tortured humanity, facing its death in cold and darkness, despairing, a shrill chorus that carried despair across the quiet starlit waters.” Multi-millionaire John Jacob Astor was lost, as well as Macy’s department store owner Isidor Straus and his wife, Ida. Businessman Benjamin Guggenheim and Bruce Ismay, chairman of the White Star Line, had died. American artist Francis Davis Millet and author Jacques Futrelle perished as well.

Newspapers published lists with the names of survivors. Over and over again, Edith must have scanned morning and afternoon editions. Richard and Percival White were not listed among them. Surely their names might have been missed. Edith sent telegrams asking officials to interview the arriving passengers. But, as the hours passed, it became increasingly clear there would be no more survivors. North Atlantic waters were too frigid. Anyone who had survived the sinking and had not been rescued by a lifeboat would have died from exposure. By the evening of April 18, edith had no choice but to acknowledge that Richard and Percival had been lost to depths of the Atlantic. As one newspaper grimly reported, ”there can be no doubt that they lost their lives in the disaster to that ship. Those who knew them will feel assured that they met the end bravely and with all the heroism that is justly attributed to those who did their duty toward the women and children.”

Bereft, Edith White returned home to The Pines with her son, Percival, to attend Richard’s memorial service at Bowdoin’s King chapel. The April 28 ceremony began when Richard’s classmates, wearing caps and gowns, marched in formation into King chapel. Somber strains of a funeral march played on the great pipe organ. President Hyde ascended the altar and addressed Richard’s classmates and guests. he described Richard’s academic abilities as well as his strength of character. Fondly recalling a game of golf they played together, Hyde remarked that he usually played poorly but happened to pull off a spectacular win on one occasion. Richard “knew the score was altogether out of my ordinary range. So he sent me a copy of the score, saying he thought I might like to keep it. i am glad now to have that thoughtful autograph.” There were tributes by his friends at the Quill and his fraternity, but the Bowdoin Orient most aptly described what the loss of Richard meant to the college. The weekly student newspaper joined “the whole community in lamenting the early death of a brilliant student, a popular and loyal undergraduate, and a true son of bowdoin.”

Frank Arthur Smith

One of Richard’s closest friends did not attend the memorial service. Instead, his classmate and fraternity brother, Frank Arthur Smith, spent his thirtieth birthday in Halifax, Nova Scotia. His was not a pleasure trip. The families of the Titanic passengers had been informed that the bodies of hundreds of the victims had been recovered. A steamer called the MacKay Bennett was taking them to halifax for identification. Smith traveled to Nova Scotia on behalf of the White family, who hoped to recover the bodies of both Richard and Percival. Frank waited anxiously at the Halifax hotel for several days before receiving a telegram from Edith’s brother-in-law, Zadoc White. Back in boston they had received word: “Richard’s body reportedly found[.] better return with it at once… look sharp for my brothers body[.] wire me fully as soon as you can.” What was thought to be Richard’s body was found clad in a brown suit, wearing white shoes. The man had fair hair and seemed to be carrying Richard’s effects, but the estimated age was listed as thirty-seven. Richard was only twenty-one. Bowdoin sent measurements taken during Richard’s last physical to assist officials in identifying the body. Finally, after several delays, the MacKay Bennett arrived in Halifax where the bodies were to be transported to a make-shift morgue in the city’s curling rink. Frank waited as the remains of those in second-class and steerage were unloaded. The corpses were sewn into canvas bags. Unlikely ever to be identified, the men, women, and children were buried in the Halifax cemetery. The bodies of first-class passengers followed. Unlike the other victims of the disaster, their bodies had been embalmed and placed in coffins aboard ship. Frank Smith was taken to view body number 169. It was indeed Richard White. The remains were so battered, so ravaged, that it was understandable that the body had been thought to be sixteen years older. Richard’s possessions fared better. he had a gold watch, keys, a bloodstone ring, and his Delta Kappa epsilon fraternity pin. After positively identifying the body, Frank inquired about Percival White. he talked with officials and checked among the other passengers yet to be identified. There were no bodies matching his description. Richard’s father was lost at sea. Frank saw that the coffin was sealed and prepared for travel. In Portland, he met members of the White family. Richard’s remains were then transported to Winchendon, Massachusetts, and were interred in a private ceremony on May 2.

instead of ornate towering monuments, edith selected a more sedate memorial to her husband and son. A tall, rough-hewn stone cross was placed in the center. Flanking it were two simple flat stones with their names, birth, and death dates.

Edith, beside herself over the loss of her husband and her son as she was, could not abandon herself to her anguish. even before the funeral was over, she had to face grim realities about her financial situation. Percival White died without a will. normally this would not be an issue, as she was the surviving spouse. However, her husband had been part owner in his family’s cotton manufacturing business. The company’s papers were written in such a way that the fate of N. D White & Sons, and her personal estate, was dependent upon learning who had died first, Percival or Richard. Inquiries were sent to Titanic survivors asking if anyone remembered seeing the men on board ship. Many replied, often providing conflicting information. One man claimed to have pulled Percival alive from the icy waters, only to have him freeze to death. He said the body had been pushed into the water after daylight. Another reported that a man matching Percival’s description was buried at sea after being taken aboard the Carpathia. Yet another man thought both of the accounts were wrong because the man pulled aboard the lifeboat had been a member of the crew wearing “coarse grey wollen socks,” and certainly not a gentleman. He claimed that no one had been buried at sea either from the lifeboat or the Carpathia. While the letters did not settle the issue of inheritance, they did shed light on Percival and Richard’s time aboard the Titanic and how they reacted to the disaster. Several said that they saw the Whites escorting women and children across the swarming decks and into the lifeboats.

A New York woman named Elizabeth Lines and her daughter Mary occupied the compartment next to the Whites’ stateroom. She described their kindness. “My girlie is a very poor sailor and though the sea was very calm, she spent Saturday in her stateroom. Mr. White was most anxious to do something for her and at last proposed that Richard should play for her. I thought this a great deal to ask of a young fellow, but he was just a dear and played and sang for my daughter.” When the Titanic collided with the iceberg, a steward told the women that there was nothing wrong and to go back to bed. it was the Whites who had alerted them to the danger. Elizabeth said that when she last saw Percival and Richard, they were “fully dressed, had overcoats, life preservers and caps. both were kind and reassuring and tried to talk calmly but it was very difficult to understand anything as the noise of escaping seam was almost deafening.”

Jean Hippach, a sixteen year-old Chicago girl who met the Whites through Elizabeth Lines, was clearly smitten with Richard. “We had such pleasant visits together besides interesting `Whist’ games we had after luncheons. I have told so many of my friends how lovely Mr. White’s son could play the mandolin and I shall never forget how perfectly lovely he was to sing all his college songs for us.” After the ship had been struck, Jean told Richard that she was dreadfully afraid, but he said, “oh, there is no need for that,” and smiled at her. Later, when they had made their way to the main deck and prepared to evacuate, Richard said, “We will have some exciting things to talk about now.” They were his last recorded words.

After Edith returned home from her son’s funeral, President Hyde went to see her every day. He often sat on the Floor and rolled a ball back and forth with baby Matilda, likely hoping that the face of a smiling child might make it possible, if only for a few seconds, for the dignified lady to forget her great loss. She was also visited by a delegation from Richard’s fraternity, Delta Kappa Epsilon. The boys made her an honorary member. in Richard’s memory, she wore his fraternity pin every day for the rest of her life. When she died, it was buried with her. In June, eighty-six seniors marched in Bowdoin’s commencement procession. even though it was a joyous occasion, the absence of Richard White was felt. In his place in line, the seniors held aloft fourteen month-old Matilda. Years later she wrote in a letter to the man who would become her husband, Jack Riley ’30, “I stood in place of Uncle Richard. At every graduation, I marched with the class of 1912 to represent him.” The closing address was given by Richard’s friend, Frank Arthur Smith, who admitted feeling a bit of melancholy about leaving “this dearest spot on Earth.” he extolled his classmates for their hard work, praised them for their great accomplishments and reminded them that they should all remember the example of their lost friend. he ended his speech with words which resonate not just to the men of the class of 1912, but to all of us today: “[W]e have the highest example life can furnish to measure up to, and the noble death of one of our number must bear fruit in our lives. So wherever we go, to do whatever work we are called, whether great or small, may we too, catch [Richard] White’s spirit with that forgetfulness of self, and, trusting in life’s great Pilot, may we answer with the best that is in us."

Special thanks to Lucy Riley Sallick who generously shared information from unpublished family letters as well as her mother’s oral history.

First published in Bowdoin, Vol 83, No. 1 Winter 2012, reproduced with permission

Comment and discuss