AWAKE! For morning in the bowl of night

Has flung the stone that puts the stars to flight…

These are the introductory lines of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, translated from the Persian by Edward FitzGerald in 1859.

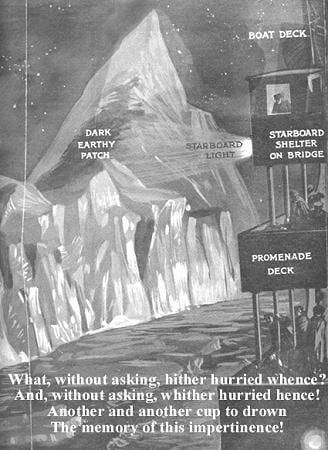

They could as easily open an elegy for a liner that sank like a stone in the dark, the world roused to aching loss of life and jolted consideration of the nature of this fragile thread.

Ironic, then, that the Rubáiyát that went down with the Titanic is all to do with the transience of human existence. It cries attention to fleeting joys and cares, that man might live for the moment - and make merry.

It is a glass of wine held up to the light. Not only in celebration, since the glass under examination throws flashes in many directions… just as the lost Rubáiyát reflects on the ship herself.

We are already intoxicated with the dream of this document. We accept the grandeur it seems to stand for - Titanic in miniature. But what, after all, is a Rubáiyát?

The very name breathes the exotic. We embrace a fable that is intrinsically fabulous, the jewelled Titanic Rubáiyát valuable above all comprehension of riches. A codex beyond compare, or so we would like to believe.

It actually only cost 405 quid.

Even allowing for inflation, the $2,025 that the volume placed on the Titanic fetched at auction in March 1912 would stand paltry comparison to any menu - or even deckchair ticket – from the ship today.

Rubái comes from the Persian word for four. Yát is a plural suffix, so that Rubáiyát is merely a number of fours. FitzGerald could accurately have named his translation The Quatrains of Omar Khayyám.

Some think Rubái gave us the word “rubber,” used in the scoring of that four-handed game of skill, auction bridge. It was bridge they were playing in the first class smoking room when the Titanic struck.

As the playing cards, symbol of chance, fell on the green baize of the tables, the iceberg was drawing ever nearer. The first class men played on, and as they played, they drank.

Nor were the chance cards confined to the passengers. Bathroom steward Charles Mackay was with his mates in their glory hole amidships – also playing bridge, but sober decks below the swilling nobs and nabobs.

While the rose blows along the river brink

With old Khayyám the ruby vintage drink:

And when the Angel with his darker draught

Draws up to thee – take that, and do not shrink.‘Tis all a chequer-board of nights and days

Where destiny with men for pieces plays:

Hither and thither moves, and mates, and slays,

And one by one back in the closet lays.

Chance is one of the great themes of the Rubáiyát, which may reflect its author’s obsession with his obstructed understanding of the universe. Omar Khayyám died in 1123 by our calendar, and with him went a gifted philosopher, mathematician, celestial observer, scholar and poet.

Khayyám was born of humble origins – his surname means tent-maker – but he rose to a life of generously-subsidised study under the benevolence of his Sultan in present-day Iran. Thus he could turn his intellect to treatises on algebra, on metaphysics, and the solution of difficulties in Euclidean geometry.

But Khayyám knew that all science goes for naught - death is the ultimate occlusion. He wrestles with this inescapability in the Rubáiyát, concentrating on the present rather than hereafter, hedonism instead of learning, the pursuit of happiness in place of knowledge.

Is this consummate betrayal by the “astronomer poet” or did he fathom one of the deepest human paradoxes – that if we are remembered at all, it may be for the flotsam and jetsam of our lives? Khayyám lives on in the Rubáiyát, but all Khayyám’s life’s work is dust.

So with the lives of Titanic’s “famous” passengers: nothing so much became the immortality of their lives as the manner of their leaving them.

Then said another – ‘Surely not in vain

My substance from the common earth was ta’en

That He who subtly wrought me into shape

Should stamp me back to common earth again.’Another said – ‘Why, ne’er a peevish boy,

Would break the bowl from which he drank in joy;

Shall he that made the vessel in pure love

And fancy, in an after rage destroy!’

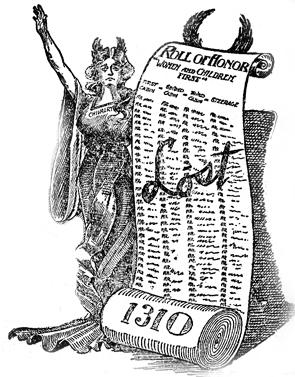

The unbreakable, unsinkable vessel was destroyed and the ‘Great Men’ died in large number. But then there were also simple men, not philosophers or mathematicians, nor railroad tycoons, nor millionaires, who did not die!

These were men who embraced the grape, a key symbol of the quatrains.

The story of the Slade brothers is well known. Humble stokers who failed to answer the march of time, missing embarkation on a ship that was doomed to sink. The brotherhood had spent too long having their final drink ashore.

The pub, rather fittingly, was ‘The Grapes.’

And, as the cock crew, those who stood before

The tavern shouted – ‘Open then the door!

You know how little while we have to stay,

And, once departed, may return no more.’

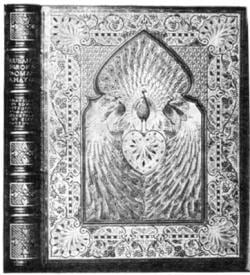

The randomness of death and the impermanence of luxury permeate the quatrains, themes reflected in the tooling of the Titanic Rubáiyát, carried out by the firm of Sangorski and Sutcliffe. Their front cover featured a resplendent peacock motif - but the inside back centralised the skull.

Those with an eye to symbolism might also note that the firm was located in Southampton Row in London.

Nothing, as it turned out, was more impermanent than the Titanic version of FitzGerald’s translation! But like the vaunted dead, the name of the book lives on. Phoenix-like, the peacock spreads his lustrous plumage through the years in further irony and emulation of Khayyám.

Yet there is a missing quatrain from the classic Rubáiyát. It was found in 1934 by a Dr Mingana, keeper of manuscripts at the John Rylands Library, in what was catalogued Arabic manuscript number 42 among the library’s antiquities.

This version of the Rubáiyát, written between 1258 and 1282, is substantially older than the document in the Bodleian library from which Edward FitzGerald wrote his translation.

The missing quatrain begins Darandah chu tarkib… and predicts that God will find fault with Khayyám’s work and destroy it.

Shades of Nostradamus, purveyor of quatrains too. And not only was the Rubáiyát destroyed at sea in 1912, but it is remarkable that so too was its very maker, Francis Sangorski.

Sangorski went for a swim on July 1, 1912, at Selsey, Sussex. He soon got into difficulties and was quickly drowned. It had taken him two years to produce the Titanic Rubáiyát, but the ocean took him in minutes.

Indeed the idols I have loved so long

Have done my credit in men’s eye much wrong:

Have drowned my honour in a shallow cup,

And sold my reputation for a song.

The Titanic volume had indeed been sold for a song, when originally £1,000 ($5,000) had been sought. Successive reductions had been necessary before New York dealer Gabriel Wells bought it at Sotheby’s for a fraction of its true worth.

Still, the Sangorski reputation for bindery and embroidery has only increased with each passing year – though he was taken from this life before the British Titanic Inquiry had even concluded.

Anyone seeking a drowning thread to a skull-adorned tale can find further evidence in the death of one Dr John Potter in 1923.

Potter, aged 75, was a Persian scholar like FitzGerald. Like FitzGerald, he produced a translation of the Rubáiyát.

On Monday evening, June 18, 1923, Potter was seen walking in the street in Castletown, Isle of Man, and thereafter vanished. “No trace was found until his body was washed up at Auchencairn, a little village in Kirkcudbright on the Solway Firth” one month later, the Times reported.

A wallet on the body identified Potter, “but there was nothing to show how Dr Potter came to be in the water.”

None answered this; but after silence spake

A vessel of a more ungainly make:

‘They sneer at me for leaning all awry;

What! did the hand then of the potter shake?’

* * * * *

The creator who moulded our modern appreciation of Khayyám was Edward FitzGerald, born in England of Irish parents, with a family seat in Waterford.

![]()

He would probably have been taken with the idea of a Great Book, containing his work, going down with the Titanic. It is probably facetious to invoke The Wreck of the Edward FitzGerald, but there it is.

His biographer, F. H. Groome, collected a fund of anecdotes from FitzGerald’s witty and epigrammatic journey through life, but “especially in regard to what filled so much of his life, his love of the sea, for seafaring men, and the estuaries and creeks of the Suffolk coast, where he used to make long summer cruises in his little yacht.”

The yacht was called The Scandal, a title FitzGerald explained by saying she was named after the staple manufacture of Woodbridge, the little town where he lived.

He thus preferred a life of ease, much akin to his literary icon.

But FitzGerald nearly fell into the same obscurity from which he rescued Khayyám.

His first edition of the Rubáiyát, unadorned by illustration, was published as a favour by Bernard Quaritch, of Castle Street, Leicester Square, London, in 1859. It had a cover price of one shilling. Only 200 were printed.

And it did not sell. It was being remaindered for a penny a copy in the bargain rack of Quaritch when it came to the attention of the poets Swinburne and Rossetti. They so championed the ruby they had found among the dross that it entered into ever more successful printings and editions.

Today an original first edition sells for $65,000.

By the time FitzGerald died, in 1883, the Rubáiyát was a literary phenomenon and a standard work, oft-quoted in Victorian salons – despite, or perhaps because of, its counter-culture message of subversive indulgence.

And if the wine you drink, the lip you press,

End in the nothing all things end in – yes –

Then fancy, while thou art, thou art but what

Thou shalt be – nothing – thou shall not be less.

Tributes to a Poet’s Memory

An interesting ceremony was performed on Saturday morning at Boulge, a little village near Woodbridge. In the churchyard there is the grave of Edward FitzGerald, the translator of the works of the Persian poet Omar Khayyám.

In 1884, Mr William Simpson, the veteran artist of the Illustrated London News, while out with the Afghan Boundary Commission, discovered the grave of Omar Khayyám and gathered from it the seeds of a rose which flourished there.

He brought them home, and plants from the seeds being reared by Mr Thiselton Dyer of Kew Gardens, it was resolved to place two bushes at the head of FitzGerald’s grave.

The trees were planted in the presence of Mr Quaritch, Mr W. Simpson, Mr Edward Clodd, Mr Clement Shorter, Mr Moncure Conway and Mr George Whale, vice president of the Omar Khayyám Club…

Mr Conway spoke in the poet’s praise on behalf of his admirers in America.

(The Times, Monday October 9, 1893, p. 5)

FitzGerald was no country bumpkin, although he avoided London and liked to confine himself to “muddy Suffolk.” He collected gems of sailor jargon and sent regular batches to his local newspaper.

One was an account of a charm about the New Moon. “When first seen, be sure to turn your money over in your pocket by way of making it grow there.” In Titanic lifeboat 13, according to Lawrence Beesley, the leading hand (probably Fred Barrett) cries out in the morning: “A new moon! Turn your money over, boys! that is, if you have any!”

FitzGerald was an exact contemporary of both Thackeray and Alfred Lord Tennyson and knew them both at Cambridge – although he professed to prefer the poetry of Tennyson's brother Frederick. He also knew Thomas Hardy.

Tennyson prefaced his poem Tiresias to Edward FitzGerald after the death of his classicist friend. FitzGerald in turn was a devotee of Aeschlyus, and had written in a letter to Professor Colwell in 1848: “As to Sophocles, I will not give up my old Titan…”

And what is the ring of the Rubáiyát - that Thomas Hardy should in 1912 compose The Convergence of the Twain on the tragedy of the Titanic, employing much the same imagery as his acquaintance FitzGerald, of earlier vintage?

In a solitude of the sea

Deep from human vanity,

And the Pride of Life that planned her, stilly couches she.And we, that now make merry in the room

They left, and summer dresses in new bloom,

Ourselves must we beneath the couch of earth

Descend, ourselves to make a couch for whom? [Rubáiyát]Dim moon-eyed fishes near

Gaze at the gilded gear

And query: "What does this vaingloriousness down here?"They say the Lion and the Lizard keep

The courts where Jamshýd gloried and drank deep:

And Bahrám, that great hunter – the wild ass

Stamps o’er his head, and he lies fast asleep. [Rubáiyát]

But perhaps this is a comparison too far, and never the twain shall meet. One could adduce Percy Bysshe Shelley in similar vein:

‘My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!’

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

Yet Thomas Hardy was a notable member of the Omar Khayyám Club, founded among the distinguished men of London in 1892 to extol the Rubáiyát and all its life-affirming properties. Is this not a convergence of sorts?

The club, both literary and bibulous, inspired an amusing imitator. The Church of the Cult of Omar was established in prohibitionist North America, swiftly gaining many adherents until quashed by the authorities.

“The [disbandment] began when a newcomer stated that the whole object of the Church was to secure permits for the purchase of liquor from the Government, under the pretence that it was necessary for sacramental purposes.”

Among those who addressed the Omar Khayyám club in its early years were Herbert Asquith, British Prime Minister when the Titanic went down, and on two occasions, James Bryce.

Bryce was destined to become His Britannic Majesty’s Ambassador at Washington, from whence to home in 1912 he stentoriously denounced the Titanic dabblings of an ‘ignorant’ Senator Smith…

Benjamin Guggenheim died on the Titanic. His general manager at the Guggenheim Mining Company was Alfred Chester Beatty – who traded casts and workings like so many trinkets. Beatty also collected Korans and Islamic art. At one point he acquired what is indisputably the oldest Rubáiyát in existence - the 12th century manuscript now residing in the Chester Beatty library in Dublin Castle.

And then there was Sir Robert Finlay and H. E. Duke, later counsel for the White Star Line and Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon respectively, who in 1910 were on opposite sides in FitzGerald v. FitzGerald, a divorce case involving the Rubáiyát translator’s nephew.

That case led in November 1912 to the sale of the Island, the ancestral castle and lands at Waterford, which had been in the FitzGerald family for generations. Another wash-out in the selfsame year!

With them the seed of wisdom did I sow,

And with my own hand laboured it to grow:

And this was all the harvest that I reaped –

‘I came like water, and like wind I go.’* * * * *

MANY treasures, appertaining to several art-crafts, have gone to the bottom, especially representing the jewellers’ art. A full inventory of these has yet to come, but the most sensational, if not the greatest, loss is that of the expensively bound Omar Khayyám, of which so much was heard when it was sold at Sotheby’s.

The stoicism of the Persian (and FitzGerald) was just what was needed in such a dire disaster, which answered exactly to the call of Fate conditioning its strangely pagan philosophy. And yet that does not reconcile us to the fearful sense of waste in every possible direction which the catastrophe has entailed on the world.

(The Graphic, April 27, 1912, p. 592)

Perhaps there was discussion of literary treasures at the dinner on the Titanic on the fateful Sunday night, April 14, given by the Wideners. Captain Smith was there, alongside the young bibliophile Harry Elkins Widener, who was bringing home many a literary jewel to festoon his already impressive collection.

Ironically, The Sphere reported on April 27, 1912, that the young Widener "was well known to all the great booksellers, particularly Mr Quaritch, by his princely purchase of rare treasures. He paid £5,000 for a first folio Shakespeare and £2,000 for a copy of Sidney's Arcadia."

There were claims that “wine flowed freely” at the gathering, although Mrs Eleanor Widener would later state to the US Inquiry that the Captain “drank absolutely no wine or intoxicating  liquor of any kind.” The Captain was lost, along with the book-collector, but a baker who broke the rules – Charles Joughin, fortifying himself with forbidden whiskey – was among the saved. The ordinary man shall celebrate indeed.

liquor of any kind.” The Captain was lost, along with the book-collector, but a baker who broke the rules – Charles Joughin, fortifying himself with forbidden whiskey – was among the saved. The ordinary man shall celebrate indeed.

Would but some winged angel, ere too late

Arrest the yet unfolded Roll of Fate

And make the stern Recorder otherwise

Enregister or quite obliterate!

And then there is the other great symbol of the Rubáiyát, which is the rose, standing for all beauty that must decay. Its relevance to the Titanic is elusive – unless one includes pure escapism, and James Cameron’s heroine of that name. She too, took her momentary pleasure. And in the cargo-hold, too!

There is even an ‘Old Rose’ connection… that was the precise hue of the carpet in the Titanic reading room. Old Rose, who threw her jewels into the ocean…

There were 1,050 precious stones in the Rubáiyát that went down. Rubies, garnets, amethysts… topazes, olivines and turquoises. The 250 amethysts formed the bunches of grapes, and the decorative ground was pure gold.

But they were all scattered and strown, with more than as many lives.

The worldly hope men set their hearts upon

Turns ashes – or it prospers; and anon,

Like snow upon the desert’s dusty face

Lighting a little hour or two – is gone!

Comment and discuss