In 2007, a Harland & Wolff engineering notebook came to light which documented changes to Titanic’s propeller configuration, compared to Olympic’s 1911 arrangement. These changes included modifications to Titanic’s port and starboard propeller specifications and a slightly larger centre propeller with three blades instead of four.

This article explores additional evidence from a turbine specialist at John Brown & Co., the firm which built these ships’ turbine engines. His papers contain a notebook with design proposals for both a three-bladed and four-bladed centre propeller configuration, which match very closely the centre propellers that Harland & Wolff’s records state were fitted to Titanic (1912) and Olympic (1911) respectively.

Introduction

Up until 2007, it appears everyone assumed that Titanic’s propeller configuration looked the same as Olympic’s 1911 configuration, with two three-bladed propellers on the port and starboard sides and a four-bladed centre propeller. However, that year a Harland & Wolff engineering notebook came to light which told a different story.1 It recorded in great detail the technical specifications for each ship they completed, including their propeller configurations. The Olympic/Titanic entries were updated up to Titanic’s completion in April 1912. The specifications for the two ships were:

Olympic

|

Wing Propellers |

Centre Propeller |

|

23 ft 6 in diameter 33 ft pitch* 160 ft area 3 blades [ * Pitch altered to 34 ft 6 in November 1911 ] |

16 ft 6 in diameter 14 ft 6 in pitch 120 ft area 4 blades |

Titanic

|

Wing Propellers |

Centre Propeller |

|

23 ft 6 in diameter 34 ft 6 in pitch [crossed out and amended to 35 ft] 160 ft area 3 blades |

17 ft diameter 14 ft 6 in pitch 120 ft area 3 blades |

The pitch of Olympic’s port and starboard propellers was increased in November 1911 and then the pitch of the port and starboard propellers was increased even further on Titanic; Titanic’s centre propeller was increased in diameter as the number of blades was reduced from four to three, keeping the same blade area by using larger blades.

This information was made available publicly in my article The Mystery of Titanic’s Central Propeller, which was published in the Titanic International Society’s Voyage journal in 2008 (issue 63) and then, subsequently, made available online at Encyclopedia-Titanica.

In truth, these changes should not have been particularly surprising. Harland & Wolff had advised J. Bruce Ismay that Titanic would be slightly faster than Olympic, yet the two ships had identical propelling machinery. The reason for this was that they had made improvements to Titanic’s propellers. Finance, Commerce and Shipping noted on 11 April 1912:

The [Titanic’s] propelling machinery consists of the same combination of reciprocating engines and turbines as is fitted in the Olympic, and in view of the modifications introduced in the propellers of the latter vessel after she had been in service, with the result of increasing her speed, it will be interesting to see whether the Titanic, in which no doubt those improvements have already been embodied, will show still better results.2

The modifications to Olympic’s propellers that the article apparently referred to were simply the increased pitches of the port and starboard propellers undertaken in November 1911 but, as we have seen, Harland & Wolff’s records show the improvements on Titanic were taken even further.

Shipbuilders of the period were always trying to find the best configuration for improved performance, balancing the need for propellers to work efficiently with the need for passenger comfort in terms of lesser vibration. Naturally, this included all aspects of propeller design, from the diameter of the propellers to the number of blades, the blade surface area and pitch of the blades. Cunard’s Lusitania and Mauretania are a case in point. In their early years of service, Cunard experimented with a number of different propeller configurations in order to determine which one was the best. In July 1908, for example, an official reported to the company’s directors ‘of the effect produced on the Lusitania by the substitution of solid four-bladed wing propellers for the three-bladed propellers previously in use’. Referring to Mauretania, they said ‘it would not be desirable to adopt four-bladed propellers of the same design as in the Lusitania until a trial has been made of the three-bladed propellers of the special design…’ (Following changes to Titanic, Olympic saw significant changes to her propellers in the 1912-13 refit, too, which included fitting her with a three-bladed centre propeller.)

The Harland & Wolff engineering notebook remains to this day the only known primary source documentation outlining in full Titanic’s propeller configuration as completed. There is, currently, no evidence at all that Titanic ever had a four-bladed propeller: Harland & Wolff’s own records state she had a three-bladed one.

In this respect, there is no mystery at all: the available evidence is clear.

(Courtesy Jason King)

Accordingly, as well as increasing the diameter slightly, the three propeller blades were larger because they each had an increase of about one-third in surface area to compensate for the reduction in blades from four to three. (Author’s collection/ Sam Halpern © 2008)

Stephen Pigott & The New Evidence

I am very grateful to Joao Goncalves for drawing my attention to some additional evidence, from the papers of Stephen Pigott, in January 2020. Pigott graduated in Mechanical and Marine Engineering from Columbia University, New York, in 1903. In June that year, he went to work as an assistant to Charles G. Curtis, who was working on the application of turbines engines for ship propulsion. Almost five years later, in March 1908, he went to London to outline the development of the Curtis Turbine to the British Admiralty. While he was on his trip, he made contacts with John Brown & Co., who had recently completed Lusitania for Cunard. That summer, he returned to the United Kingdom on the Cunarder to work with John Brown & Co. for four to six months. Instead, Managing Director Sir Thomas Bell invited Pigott to work there on a permanent basis as a turbine specialist. (He was promoted to Engine Works Director in 1919 and rose ultimately to Managing Director after Bell retired in 1938. King George VI knighted him the following year. Following his retirement in 1949, Pigott passed away in 1955.)

Harland & Wolff opted to use a combination of triple-expansion reciprocating engines and a low-pressure turbine to make sure Olympic and her sisters could maintain a service speed of 21 knots with ample power in reserve. However, only Britannic’s turbine was built in Belfast. When Olympic and Titanic were under construction, their turbines were subcontracted to John Brown & Co. at Clydebank.

Their turbines were an important element of their propelling machinery. In 1911, Olympic’s chief engineer indicated that her propelling machinery had developed 59,000 horsepower with the reciprocating engines running at 83 revolutions per minute*. The turbine engine contributed about a third of the total power output. It was a large, powerful unit and comparable with the turbine engines on Lusitania and Mauretania.

[ * The power output from the reciprocating engines was typically given in indicated horsepower (IHP) whereas the turbine’s output was given in shaft horsepower (SHP). However, the figure of 59,000 horsepower was not qualified.]

Accordingly, Pigott became involved with the ‘Olympic’ class ships through his turbine work at John Brown & Co. His papers include a notebook, containing propeller design data for various ships built by the firm, including Beagle (launched April 1909), Bulldog (launched November 1909), Foxhound (launched December 1909), Bristol (launched February 1910), Brisk (launched September 1910), Indefatigable (launched October 1909), Petersburg (launched April 1910), Yarmouth (launched April 1911) and Argyllshire (launched February 1911). The notebook itself appears undated, but the vessels were all completed in either 1910 or 1911, with the exception of Yarmouth (April 1912).

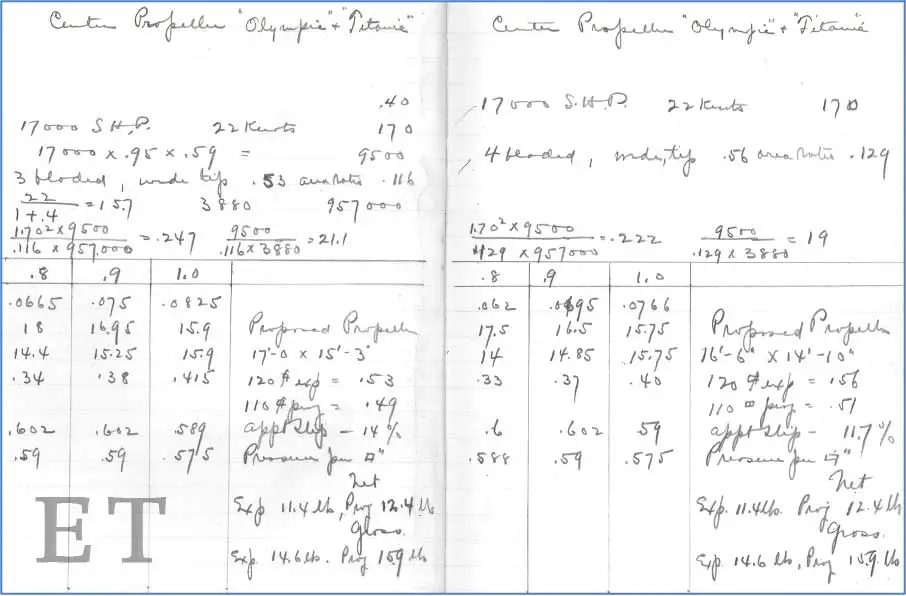

Intriguingly, the propeller data in the notebook also includes proposed centre propeller configurations for Olympic and Titanic on a double page. The left hand page contains specifications for one ‘proposed propeller’ and the right hand page contains specifications for another option:

On the left hand page, near the top left, the ‘proposed propeller’ specification states ‘3 bladed’ and then, on the right hand page in the same general location, it states ‘4 bladed’. The notebook contains lots of technical data, including a calculation that the turbine would be developing 17,000 shaft horsepower while the ship was making 22 knots and the centre propeller was running at 170 revolutions per minute (see third line from top, left hand page, and second line from top, right hand page).

(University of Glasgow Archives & Special Collections, Papers of Sir Stephen Pigott, GB248 UGC100/3/7)

What is particularly interesting is that the two ‘proposed propeller’ configurations include a different number of blades. The left hand page is that of a three-bladed propeller and the right hand page is that of a four-bladed propeller. This is significant new, primary source evidence which demonstrates that both three- and four-bladed propeller configurations were being considered for Olympic and Titanic’s turbine driven centre propeller, while these ships were under construction.

How do these ‘proposed propellers’ compare with the propellers that Harland & Wolff’s own records state were fitted to Olympic and Titanic as completed in 1911 and 1912?

The following tables compare the proposed four-bladed propeller from the notebook in the Pigott papers with Olympic’s four-bladed propeller in 1911 and the proposed three-bladed propeller from the notebook with Titanic’s three-bladed propeller as fitted in 1912. They are almost identical:

Olympic

|

‘Proposed Propeller’ |

Centre Propeller (fitted 1911) |

|

16 ft 6 in diameter 14 ft 10 in pitch 120 ft area 4 blades |

16 ft 6 in diameter 14 ft 6 in pitch 120 ft area 4 blades |

Titanic

|

‘Proposed Propeller’ |

Centre Propeller (fitted 1912) |

|

17 ft diameter 15 ft 3 in pitch 120 ft area 3 blades |

17 ft diameter 14 ft 6 in pitch 120 ft area 3 blades |

The sole difference between the two ‘proposed propellers’ in the Pigott notebook and both ships as completed is simply that, in both cases, the pitch of the propeller blades was reduced to 14 feet 6 inches (the higher pitches are highlighted in bold above).

The propeller diameters, blade areas and number of blades are identical.

It appears that the proposed three-bladed centre propeller had an estimated ‘appt. [apparent] slip’ of 14 per cent, whereas the four-bladed centre propeller had 11.7 per cent. A reduction in propeller slip is beneficial because it means the propeller is more efficient. For the centre propellers fitted to each ship as completed, the pitch was 14 feet 6 inches. This is, in essence, the distance that a propeller would move in a single revolution if it was 100 per cent efficient. In reality, propellers are never that efficient. There is ‘slip’, which means that the actual distance is less than the pitch of the propeller blades.

In the case of a propeller with a slip of 14 per cent, this means it is working at 86 per cent of its maximum efficiency, whereas a propeller with a slip of 11.7 per cent is working at 88.3 per cent of its maximum efficiency.

Reducing propeller slip could have a dramatic beneficial impact on a ship’s performance. By 1936, propeller design had advanced enormously compared to a generation earlier. This is easy to demonstrate using the example of Cunard’s Aquitania, which was similar in size to Olympic and Titanic. She left Southampton on 8 April 1936 for her 260th westbound crossing to New York. The average number of revolutions per minute on her four propellers was 178.6, which allowed her to average 23.01 knots. However, the propeller slip was 14.3 per cent.

The next month, she set out westbound with a new set of propellers. The new propellers reflected the benefit of experience in propeller design unavailable when she was completed in 1914. This time, the new propellers proved much more efficient, reducing propeller slip to 6 per cent. In consequence, although the average number of revolutions decreased by almost 7.6 per cent, Aquitania’s average speed for the entire crossing rose almost 2.6 per cent to 23.6 knots. Comparing the best day’s run she made on each crossing was even more striking: the average revolutions decreased 6.3 per cent as her average speed rose almost 8.6 per cent, from 23.36 knots to 25.36 knots. The new propellers gave the option of increasing her speed substantially for the same fuel consumption or maintaining the same speed with reduced fuel consumption and operating costs.

In Titanic’s case, it has been estimated that she would make a speed of 23.39 knots through the water with her reciprocating engines running at 80 revolutions (not her maximum).3 However, the apparent propeller slip would be 15.4 per cent. If it had been possible to reduce her propeller slip to 6 per cent (as on Aquitania in 1936), then she would have made a speed of 25.99 knots – a dramatic difference.

Improvements of such magnitude were far into the future while Olympic and Titanic were being built, but reducing propeller slip as much as possible was one of the key goals in propeller design. Although the calculations in the Pigott notebook indicated the proposed four-bladed propeller was more efficient than the proposed three-bladed one in that it had lower slip, that was based on design specifications which changed subsequently. Comparing the proposed four-bladed propeller with the centre propeller fitted to Olympic in 1911, the pitch was reduced 2.2 per cent; in the case of the proposed three-bladed propeller and how it compared with the centre propeller fitted to Titanic in 1912, the pitch was reduced 5 per cent. Any calculations they made as to what the slip would be with the new, reduced propeller pitch are not known. If the belief still held that a four-bladed propeller had lower slip, then it might explain why Olympic was completed with a four-bladed centre propeller before a three-bladed centre propeller was used on Titanic.4

The notebook data indicates that the low pressure turbine would be developing about 17,000 shaft horsepower while running at 170 revolutions per minute. (The ship’s speed was given as 22 knots.) These figures for the power developed and revolutions are identical to those supplied by John Brown & Co. to the British Board of Trade’s Principal Officer, A. Boyle, in Glasgow, in July 1910. The Board were advised then that Titanic’s turbine was identical to Olympic’s and that ‘the power to be developed is estimated at 17,000 SHP, running at 170 revolutions per minute at an initial pressure of 8 to 9 lbs per square inch absolute’.

Harland & Wolff's Combination Machinery

Harland & Wolff used combination propelling machinery, consisting of two reciprocating engines exhausting steam into a low-pressure turbine, on a number of different ships. None were on the same scale as the powerful propelling machinery on the ‘Olympic’ class ships and there were many differences between the ships that were fitted with this arrangement of propelling machinery. They were built for different owners, varied in terms of size, speed, power output and intended service. What they all had in common was that their port and starboard propellers were all three-bladed.

Following Laurentic’s completion, Olympic was the second ship to be fitted with combination propelling machinery. She was also something of an exception. Harland & Wolff’s records show Laurentic (1909), Demosthenes (1911), Titanic (1912), Arlanza (1912), Andes (1913), Ceramic (1913), Katoomba (1913) and Alcantara (1914) all employed a propeller configuration consisting of three propellers which were all three-bladed. From April 1909 to January 1914, Olympic was the sole ship they built that was fitted with a four-bladed centre propeller, until Orduna was completed in January 1914.5 Even then, Olympic was fitted with a three-bladed centre propeller, similar to that on Titanic, when she emerged from her first major refit in March 1913. Later, more of the ships they completed with combination propelling machinery were fitted with four-bladed centre propellers, including Britannic (1915). We also know Olympic reverted subsequently to a four-bladed configuration. In fact, the ships Harland & Wolff built with this type of propulsion system were balanced closely between those with a three-bladed centre propeller and those with a four-bladed centre propeller.*

[ * The ships with a three-bladed centre propeller consisted of Laurentic (1909), Demosthenes (1911), Titanic (1912), Arlanza (1912), Andes (1913), Ceramic (1913), Alcantara (1914), Katoomba (1913), Euripides (1914) Melita (1918) and Minnedosa (1918).

Those with a four-bladed centre propeller consisted of Olympic (1911), Britannic (1914), Justicia (1917), Orduna (1914), Orbita (1915), Belgic (1917), Almanzora (1915), Orca (1918), Regina (1919) and Pittsburgh (1920). However, Olympic is known to have been fitted with a three-bladed centre propeller when she completed her refit in March 1913.

Two ships laid down in 1914, Red Star’s Nederland and White Star’s Germanic, were intended to be powered using the combination propelling machinery system, however details of their intended propeller configuration do not seem to have survived. White Star’s Laurentic (1927) has also been omitted from this comparison.]

No new designs were made after 1914 for combination propelling machinery installations, according to Cuthbert Coulson Pounder, who worked for Harland & Wolff for many years. The First World War postponed the completion of a number of ships, meaning that they were completed either late in the war or after the war but were, essentially, pre-war designs. Altogether, over twenty ships were completed with the combination arrangement by Harland & Wolff, ending with the bizarre decision to use it on White Star’s second Laurentic (1927) and the even more bizarre decision to complete her as a coal burner, eight years after Olympic had been converted to oil fuel.

Summary

Since 2007-08, we have known that Harland & Wolff’s records for the completed Titanic state that she had an increased pitch on her port and starboard propellers compared to Olympic; and that she had a slightly larger centre propeller with the same blade area obtained from using three blades rather than four.

We now know, too, that both a three and four-bladed centre propeller configuration were being examined while the sister ships were under construction. Stephen Pigott was working for John Brown & Co., who built the turbine engines for both ships. The three and four-bladed designs in the notebook from the Stephen Pigott papers are identical to the centre propellers fitted to Titanic and Olympic, respectively, with the sole exception that the pitch of the blades was reduced in each case. This notebook provides strong circumstantial evidence to support the Harland & Wolff documentation.

Both the engineering notebook from Harland & Wolff and the propeller specification notebook from the Pigott papers are primary sources. These original documents are contemporaneous with the completion and construction of Olympic and Titanic. Accordingly, they rank far above the vast body of secondary source material on the subject, including books, television programmes and websites which simply repeated the assumption that Titanic’s propellers were the same as her older sister.

We have also seen, merely as a matter of general interest, that Harland & Wolff built a number of different ships with combination propelling machinery and opted for both three and four-bladed centre propeller configurations. However, in the early years it was Olympic which was the odd one out in that she had a four-bladed centre propeller whereas the other ships they completed had a three-bladed one.

It is important to be open minded to new evidence as it becomes available. There is still much to learn.

Notes

- It is unclear when the Harland & Wolff engineering notebook, which is one of a series of similar volumes, was deposited with the Public Records Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI). From 1972 to 1994, there were thirteen separate deposits of material from Harland & Wolff. The date of deposit for this particular item was not recorded.

- I am grateful to George Behe for sharing this article with me.

- See Halpern, Sam. Speed and Revolutions: The Development of a Slip Table for the SS Titanic. (Revised 16 October 2015) (Accessed 17 February 2020.)

- When the Shipbuilder devoted a ‘special number’ to Olympic and Titanic in the summer of 1911, they described the propelling machinery in detail. Their description was generic and generally applied to both vessels, including the boilers and engines. However, when it explained the propeller configuration, the relevant paragraph was phrased to apply to Olympic only (page 60):

‘The wing propellers of the Olympic are three bladed and have a diameter of 23 feet 6 inches…The centre or turbine propeller, which is illustrated by Fig. 61, has four blades and is built solid of manganese bronze. The diameter in this case is 16 feet 6 inches’.

The publication did not explicitly say that Titanic’s propellers would be different, nor should we read too much into it, but it is a curious detail. - In June 2018, Victor Vila of the Brazilian Titanic Historical Society made an observation relating to the builder’s half model of Olympic and Titanic. The half model was photographed c. April 1910 by Robert Welch. His photograph was taken from the starboard side, aft. When it was photographed, no starboard propeller was fitted and the port side did not exist on the half-model, however the centre propeller depicted on the model appears to be a representation of a three-bladed one.

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, I owe my thanks to Joao Goncalves for drawing my attention to the notebook in the Stephen Pigott papers.

All image contributors are acknowledged in the captions and I am grateful for them allowing me to use their material. I have benefited from discussions with many people about propeller design over the years and have also cited a number of people directly in the endnote references.

I am grateful to Avril Loughlin and the Public Records Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI) for their assistance; Claire Daniel and the staff of Archives & Special Collections, Glasgow University.

And, finally, my apologies for anyone who I have inadvertently missed out.

For further information, see:

Chirnside, Mark. RMS Aquitania: The “Ship Beautiful” History Press; 2008.

Chirnside, Mark. The Mystery of Titanic’s Central Propeller, which was published in the Titanic International Society’s Voyage journal in 2008 (issue 63) and then, subsequently, made available online at Encyclopedia-Titanica.

Chirnside, Mark. Titanic’s Centre Propeller: Dossier. Mark Chirnside’s Reception Room. November 2016.

This article was first published in the British Titanic Society’s Atlantic Daily Bulletin July 2020: Pages 16-21.

Comment and discuss