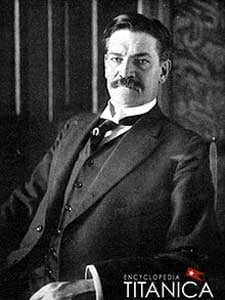

Best known, perhaps, as the man who escaped in pajamas from the sinking of the Titanic – some accounts even claimed he was naked – 27-year-old Philadelphia banker Robert Williams Daniel was one of the disaster's most prominent first-class survivors about whom the exact details of his escape have gone unrecorded, resulting in speculation and an unfair assessment of his character. This article seeks to establish what is known about Robert Daniel's movements aboard Titanic on the night it struck an iceberg and what may have happened to him as the great ship went down in the early morning hours of April 15, 1912.

Chapter 1: Who was Robert Daniel?

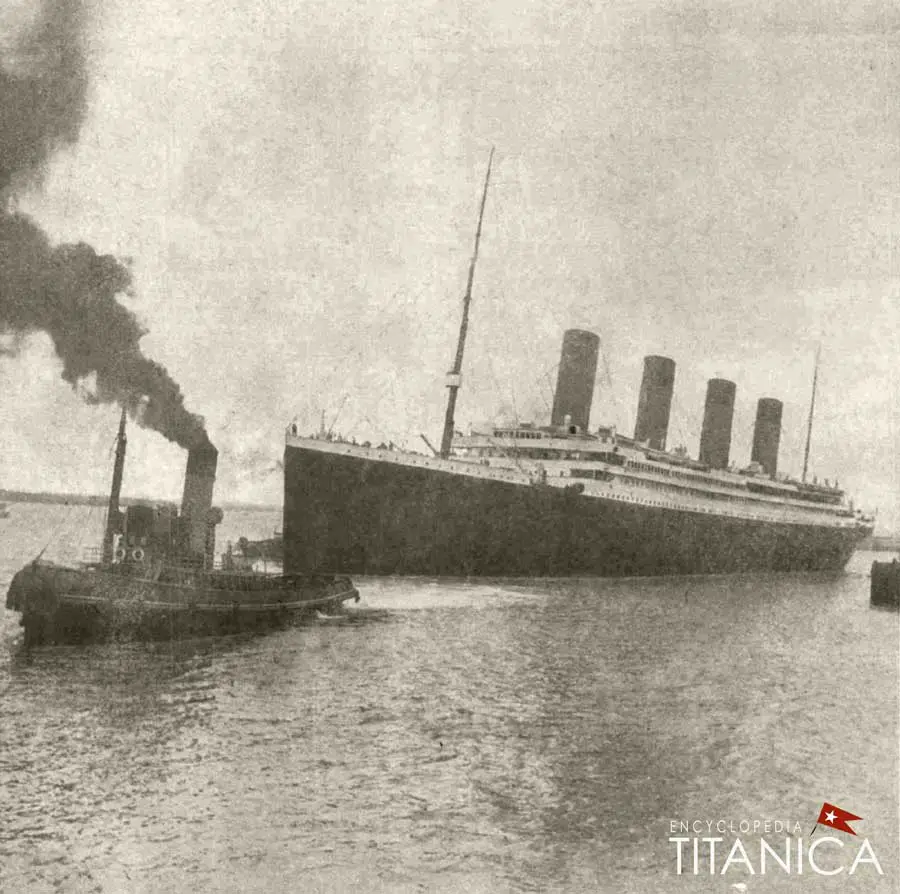

On April 10, 1912, following a business trip in connection with the London branch of his namesake Philadelphia-based banking enterprise, Robert W. Daniel, tall, slim, good-looking, boarded Titanic at Southampton. Although he'd recently struck out on his own in that field after a few years spent with a railroad office and an insurance firm, Robert was still associated as a board member with the Philadelphia banking and brokerage firm of Shillard-Smith, Daniel & Co.

(Courtesy of Michael Beatty)

Born in 1884 - he would turn 28 on September 11, 1912 – Daniel was an ambitious, athletic, well-spoken University of Virginia graduate who was particularly proud of his family's political prominence. His great-great-grandfather had been the first U.S. Attorney General and the seventh governor of Virginia, his grandfather was a U.S. Supreme Court judge and a cousin had been a senator. His attorney father, James Robertson Vivian Daniel, had died in 1904 and Robert, along with two younger brothers, was close to his mother, Hallie Wise Daniel, who especially doted on Robert.

His family today still reveres Robert's memory. "He was a very charming man, but he was difficult to get to know," his daughter-in-law, Linda Daniel, said. "He was an introvert." That didn't keep him from the habit of writing "warm, loving letters" to family members, Linda recalled.

He was "strong, bold and agile," according to his niece, Helen Daniel Rodman. Robert had proved that the year before he sailed on Titanic when he not only survived the Carlton Hotel fire in London but managed to save from the burning building a friend who'd become overwhelmed by the smoke.

Chapter 2: Titanic's maiden voyage

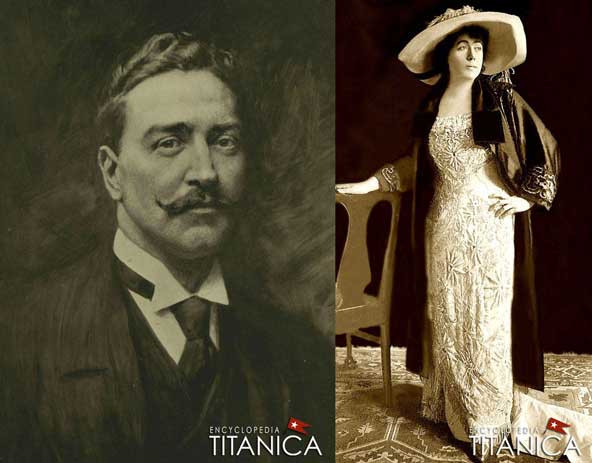

Helen Rodman also pointed out that her Uncle Robert was a "handsome single gentleman" who no doubt "wined and dined and wooed several young ladies" aboard Titanic which was his "sixth crossing." While there was no known romantic tryst aboard, he did meet his future first wife on the rescue ship Carpathia a few days later: Eloise Hughes Smith was aboard Titanic with her husband, Lucian, returning from their European honeymoon. Lucian would not survive.

(Courtesy of Michael Poirier)

Unfortunately, very little is known of Robert Daniel's experiences during the first five days of Titanic's maiden voyage; however, it's recorded that while the ship was stopped at Cherbourg, the liner's first port of call, at 6:22 in the evening of April 10th, he sent a Marconi telegram to a friend in his hometown of Richmond, Virginia, simply stating "On board Titanic."

Robert had brought with him apparel and other personal effects typical of a well-dressed young man. Valued at $4,583.25, his wardrobe included three new suits of clothes, a cutaway jacket, a Tuxedo, three and a half dozen shirts and neckties, hats, riding clothes, boots and eight pairs of shoes. In addition, he had $1,743.20 in cash which he deposited in the Purser's safe. His later insurance claim included $8 for the loss of two pairs of tennis shoes so it's possible he may have used Titanic's Squash Court at some point on the trip. Robert also had with him ladies' gifts for either his mother or girlfriends that consisted of Irish lace, a pair of pearl earrings and assorted flower ornaments.

(Daily Mirror)

The Washington Herald of April 19th would mention that Daniel understood wireless telegraphy and that he spent time during the voyage assisting Titanic's senior Marconi operator, John (Jack) Phillips. This sounds highly unlikely. The Daniel family does, however, verify that Robert learned wireless telegraphy while employed by the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad Co. eight years earlier.

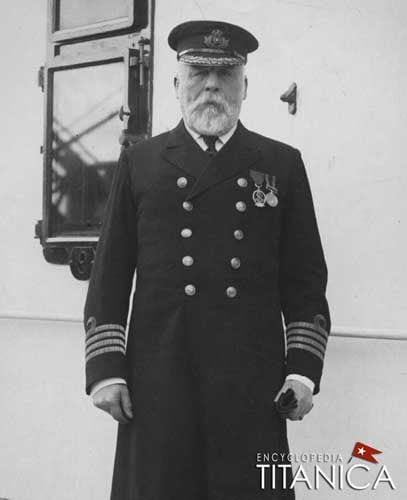

As his clothing indicated, Robert was prepared for an active social life on Titanic. Indeed, he made friends and business contacts with many of the notable men and women whom he encountered in First Class. Some of the first people of interest he met were Maj. Archie Butt, President Taft's military attaché, and sportsman Clarence Moore. They met on deck the afternoon Titanic set out from Southampton. The Philadelphia Inquirer of April 21st recorded that Robert stood near the men and "pointed out some prominent people" around them, including the ship's captain, Edward J. Smith, artist Frank Millet, and various society people he knew.

(Library of Congress)

"I had met Mr. Moore and Maj. Butt for the first time on the day that the Titanic sailed," Robert would later tell the Washington Post. "Mr. Moore was one of the most genial and charming men I had ever known." He recalled that "Butt was one of the finest fellows I ever knew."

En route, Robert befriended historian Col. Archibald Gracie, businessmen Howard B. Case and Percival White, tennis star Richard Norris (Dick) Williams, his father Duane Williams, and railroad tycoon Charles M. Hays. "The last I saw of him was in the Turkish Bath," Robert recalled of Hays to a reporter for The New York Sun.

Robert later told the family of Percival White, who died in the disaster along with his son, Richard, that he had last seen the elder White on the afternoon of April 14, the day Titanic struck ice.

(Library of Congress)

On Titanic, Robert also met Isidor and Ida Straus and John B. Thayer, his wife, Marian, and their teenage son, Jack. He may not have met the Arthur Ryerson family but he was aware of their purpose for being on board.

"Everyone knew the sad news which was responsible for the Ryersons being aboard the Titanic," Robert told The Philadelphia Inquirer. "It had been disseminated among the first class passengers and the heartstrings were touched by the grief of the parents and their three children who were in mourning over the death of the oldest son, a victim of an automobile accident."

Robert even rubbed elbows with millionaire John Jacob Astor IV - on honeymoon with his bride, formerly Madeleine Force - and Walter M. Clark, head of a sugar company, traveling with his wife, Virginia, on what has been described as a delayed honeymoon.

(Randy Bigham)

Because their staterooms were located near one another, Robert also knew fashion columnist and stylist Edith L. Rosenbaum whom he had met previously in Cannes. Edith was berthed in forward starboard side cabin A-11. Robert's room number on A Deck isn't known, but a clue is found in the memory Edith shared with a friend in later years. At that time, she said Robert "was in a cabin around the corner from me." Although only a vague indication, it suggests he may have been booked in A-15. Robert never said more about his cabin except that he "had an inside room."

Chapter 3: Gamin de Pycombe

Whatever stateroom he occupied, Robert shared it, at least occasionally, with the champion French bulldog he had just purchased (for a then whopping $750) and named Gamin de Pycombe. Roughly translated, the name means "Little boy from Pycombe." Pycombe was a village in West Sussex, England, just a few miles north of the popular seaside resort of Brighton.

As would be reported in The New York Herald of April 21st, fellow First Class passenger Nella Goldenberg said that "so many fine dogs were on board the Titanic that a show was being arranged for the last day of the voyage." If this was true, might Robert have arranged for Gamin to participate in the dog show? According to Nella, Robert's dog was such a good representation of his breed that he "was sure to capture ribbons in this country."

(Getty Images)

Robert certainly was proud of Gamin. The Richmond Times-Dispatch noted on April 22nd that he'd written in an April 4th letter from Paris to his mother that he was eager to bring home a "thoroughbred bull pup."

Gamin spent most of his time in the ship's kennels, located at the aft end of the Boat Deck in the rear of the fourth funnel deck house. As this was Second Class promenade space, the kennels attracted the attention of a 7-year-old British child, Eva Hart, traveling with her father and mother, Benjamin and Esther, who were emigrating from Ilford, Essex to Winnipeg, Canada. Of her time aboard Titanic, Eva claimed in later life that her mother experienced a premonition of disaster in the weeks leading up to the maiden voyage, and so certain was she that something was going to happen that she refused to sleep at night, only resting during the day.

"I was about all day with my father because, as I say, my mother was sleeping, and to my great joy, I found there were some dogs on board," Eva recalled. "They weren't roaming about, they were all in a row of kennels and cages and things at the end of the ship and there was one little French bulldog that I took a great fancy to - and my father was quite friendly with, I think, one of the crew who looked after them and, every day, he used to let me go down and play with this little dog, and from that day to this, they have been my favorite dogs, the French bulldogs.

Eva added that she grew attached to Gamin "because I had been quite sad to leave my own dog at home with my grandmother." Over the next few days at sea, she "spent a great deal of time playing" with him.

(Brian Harris | Alamy Stock Photo)

She went on to remember:

I loved this animal so much that I would hurry through my breakfast each morning and then rush off to find him, as by then I hadn't seen him for more than 12 hours. At the age of 7, that length of time is an eternity. I was completely fascinated by him and hated being separated for very long. My father saw how fond I had become of this small, flat faced, endearing dog and promised me, 'When we get to Canada, I will buy you one.'

By Sunday, April 14th, after five days at sea, Eva was much enjoying her routine of playing with Robert's dog, and after lunch with her parents she went to find Gamin, spending the early afternoon with him for the last time.

Chapter 4: What happened that night

As afternoon turned to evening on Titanic, Robert Daniel dressed to have dinner in the dining saloon. After his meal, Robert joined other passengers for a concert played by the ship's band in the reception area, just outside of the dining room. The band so regularly performed there that Robert called the space the "music room." The evening was festive, many passengers attired in evening clothes; Robert particularly remembered some of the ladies "wearing diamonds."

Robert enjoyed smoking cigarettes, perhaps even a pipe (judging from his wardrobe inventory), which he did that evening in the smoking room. While there, he observed a bridge whist game underway at which Archie Butt and Clarence Moore were among the players. Robert recalled he left to return to his stateroom at about 9 p.m., claiming in one account that it was the last time he saw Butt and Moore.

"I spoke to the fourth officer just before I went to my cabin," according to Robert, "and he told me he was in charge while the captain was at dinner. Then I remembered I had heard Ismay was giving a banquet. The fourth officer said the skipper was coming up 'pretty soon' to relieve him."

(Library of Congress)

It should be noted that it was not Fourth Officer Joseph Boxhall but Sixth Officer James Moody who had the watch at the time Robert would have spoken to an officer in charge. It is known that Capt. Smith returned to the bridge at about 8:50 p.m. after attending the dinner party in the restaurant which had been planned by Philadelphia social leader Eleanor Widener - not Ismay - although the chairman of the White Star Line was present in the restaurant that night.

By all accounts in the American newspapers, Robert was "in my stateroom" when Titanic hit the iceberg at about 11:40 p.m. He recounted:

I was asleep in my berth when the collision came and so cannot tell how we happened to hit that berg or what occurred immediately afterwards. I got up and looked out of my stateroom door; but all seemed to be quiet and I went back to bed again. We were about fifty miles ahead of our schedule at the time the accident happened and were running at about a twenty-mile-an-hour rate. Everybody on board had been talking all along about how we were trying to beat the Olympic's record for the Western trip and many pools were made on each day's run.

Robert's initial reaction to the accident was similarly reported in various papers. He was not much bothered by the sensation of the collision; he called it a "quiver" in one article. Also, he may not have been alone in his cabin at the time – he was possibly entertaining a young woman – which further distracted him. He refers, confusingly, to "dictating to a stenographer" in his room when the crash with the berg happened. He probably meant he was dictating to a Dictaphone or similar recording device; if he was with a female, her identity is unknown.

(Randy Bigham)

To the New York Press, Robert explained in details that were repeated with slight variations in other interviews. He said that:

there practically was no shock when the Titanic struck the iceberg. I was in my stateroom and ready for bed when the collision came. All I felt was a slight jar. Out of curiosity only, I dressed and went on deck. There, I learned we had rammed the ice mountain but, on the heels of that information, came the assurance that there was no danger. Indeed, there seemed to be little cause for apprehension.

Thanks to Robert's friend, Edith Rosenbaum, booked in a nearby cabin, more is known about Robert's brief excursion on deck. Having also felt the crash with the berg as she was about to retire for the night, she stopped by Robert's room and called out to him, "Come along, let's see what has happened."

Robert put on a bathrobe over his pajamas and with Edith walked out onto the enclosed promenade deck on the starboard side.

There were only five other people there when Robert and Edith came outside. One man stood at the rail looking at a mammoth, glistening, greyish mass in the distance. It was huge; like a floating building, Edith thought. Quickly joined by several others running up on deck in various stages of undress, Edith asked, "What on earth is that?"

"Well, madam," someone replied, "that is an iceberg."

The sea was perfectly calm and the starry sky reassured Robert and Edith. The pair regarded it as a great joke that they'd hit an iceberg; there was no sign of any panic as no one yet realized the peril.

(Randy Bigham)

Robert and Edith had only been on the outer deck for a couple of minutes looking at the berg when Titanic's engines started up again. Seeing the ship was moving and still joking about the collision, the two friends ran forward to the open promenade that overlooked the Well Deck.

Some of the ice that had broken off the berg onto the Well Deck apparently fell onto the forward end of A Deck, too. Edith recalled that she and Robert picked up bits of the ice scattered about and playfully started a snowball fight. For a few moments they enjoyed themselves.

When telling this story, Edith seldom mentioned the name of her companion, but in a letter to Walter Lord many years later she confirmed his identity: "Mr. Daniel and I went on deck and threw snowballs after the accident."

After watching a number of crewmen walk around the Well Deck, broken ice crunching under their feet, Robert and Edith were joined by "officers" – they were more likely stewards - who told them there had been an accident but "there was no danger whatever" and the best thing they could do was to go back to their cabins.

"After receiving direct assurance from more than one officer that the Titanic could not sink, I went back to bed," Robert said.

Edith remembered doing the same. "He [Robert] went back to bed just as I did as we thought there was no danger," she told Lord.

Perhaps snuggling with Gamin de Pycombe, who was spending the night in the cabin with him, Robert fell asleep again.

"A little later I heard someone crying that the [life]boats were being manned and I got frightened," he admitted. "So I wrapped an overcoat about me and went on deck. On the way, I grabbed a lifebelt and tied it on." He also claimed the sound of people "running and scampering" along the deck above startled him and that a steward, shortly afterward, told him to put on a lifebelt.

Robert was actually still clad in pajamas, later referred to by Árpád Lengyel, a Carpathia physician, as a "woolen sleeping garment," and the coat Robert mentioned was really only a dressing gown or bathrobe, as he called it in other accounts. In another account, Dr. Lengyel described it as a "red nightshirt."

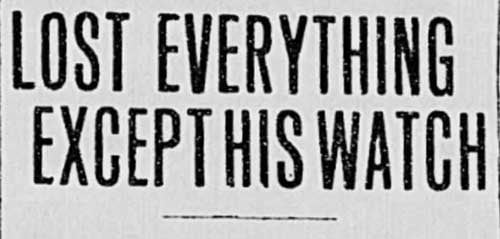

The only other thing Robert wore, aside from shoes, was a pocket watch that had belonged to his late father. Ready cash, in the amount of $73.05, he had left in his cabin. A story, widely syndicated later, claimed he left behind $3 million in securities. He finally denied this in The Wall Street Journal of April 20th.

(Randy Bigham)

Robert tied his dad's watch around his neck as he hurriedly headed topside. Going out into the corridor, he remembered his neighbor, Edith Rosenbaum, and started for her room to make sure she was awake and aware of what was happening.

In a curtailed interview that she gave to The New York Times, Edith related:

Mr. Daniels [sic], who had a cabin near mine, called to me in the corridor, 'Have you put on your life-preserver? I understand the order has gone out for all passengers to be provided with them.'

In a more descriptive account that she penned for Cassell's Magazine, Edith wrote:

I started to undress, and was nearly in bed when a young man I knew came to my door and said, 'There's a man saying that there's an order given out that we are to put on lifebelts.' I said, 'What for?' 'Well,' he said, 'that is the order.' So I slipped on a wrapper, and went out to interview this man, who was trembling and crying and very much unnerved, and [he] said, 'We have to put on lifebelts.'

Given Edith's penchant for dramatics, she may have been exaggerating Robert's state of anxiety. But, scared or not, he was ultimately clear-headed. The year before, he had stood on a fourth floor ledge to save a friend in the fire that had engulfed London's Carlton Hotel. Robert was definitely prepared for the challenge that lay ahead.

(Michael Beatty)

While Edith put on her lifebelt, Robert went back to his room to comfort Gamin who was becoming upset by the commotion of people scurrying about.

Edith, who didn't take long to get dressed and retrieve her lifebelt, went by Robert's cabin on her way up on deck. She recalled:

In going to the lounge, I passed the open door of the friend's room who had told me to put on a lifebelt. He said, 'Do you think we shall have to leave the boat?' I said, 'Certainly not!' This friend had just purchased a beautiful bulldog in France, and it was whining and moaning. I remember taking it and tucking it under the bedcovers, and patting its head, and then we went to the lounge on A Deck.

She later admitted that, had she known the danger they were in, she would have taken the dog with her.

Chapter 5: The myth of Boat 7

Robert and Edith - he barely dressed and she enwrapped in a full-length broadtail fur and two fox stoles - entered the lounge where fellow passengers, recently roused from their beds, were congregating. Here, the shipboard acquaintances parted company. In a little over an hour, Edith would enter lifeboat 11, escaping Titanic 45 minutes before the liner sank. How Robert Daniel survived the disaster would become a mystery that has perplexed historians - even his family - for 109 years.

(British Titanic Society)

In examining the preponderance of stories, both Robert's own accounts and those of others, one certainty can be established: he did not abandon ship in the first lifeboat launched, No. 7, which has been cited, more or less officially, as the boat in which he survived. In the articles and interviews that flooded the daily papers following the sinking, hyperbole abounded, nuggets of truth sometimes barely recognizable. A number of survivors were unclear in their memories while some, no doubt, exaggerated their tales. But with looming deadlines and the pressure to produce good copy for their editors, many reporters were also either clumsy in compiling notes or purposefully misleading in an effort to submit a dramatic story that might achieve optimum placement.

One such sensational untruth appeared in The New York Press of April 19th (and was afterwards syndicated) which claimed Robert jumped overboard and was pulled onto a lifeboat containing Ruth Dodge, who gave him a blanket, and her small son. The article's author said the boat that saved Robert also included "a Frenchman, an apprentice boy, and several women." Ruth escaped in Lifeboat No. 5 but was indeed later transferred with her son, Washington Dodge, Jr., to No. 7. Yet The New York Press accountof Robert's escape is sketchy at best, containing few verifiable facts and, more often than not, veers into the ridiculous, such as when Robert supposedly claimed to the unnamed writer that as the apprentice crewmember aboard "was too young to handle such a situation," he, Robert, "took charge and began quieting the women."

The reality is Boat 7 was not commanded by an apprentice but by Titanic Lookout George Hogg, who was 29 years old, Robert's senior by two years. The other crewmen aboard were deck hands Archie Jewel, 23 (only four years younger than Robert), and William Weller, 30. What's more, the estimated 28 occupants of this boat were about evenly divided between men and women, some of them married couples. And, most importantly, no survivor in Boat 7 recalled picking up anyone from the water during or after the sinking. Writers for The New York Press were certainly vying for sensationalism in its April 19th edition. In the very next column to the story on Robert was an article about another survivor with the headline "Lady Duff Gordon Knocked Insensible by the Crash," an entirely fabricated story.

(Betsy Smith McLain | Catherine Gay)

A similarly fantasized account about Robert that appeared in the April 19th issue of The New York Herald claimed he swam to a lifeboat that contained honeymooner Eloise Hughes Smith. Robert did become acquainted with Eloise, but only aboard Carpathia, helping her descend the gangway when the ship docked days later. Perhaps a reporter assumed the pair had survived the sinking in the same lifeboat - or knew better and stated it anyway. Eloise had actually been saved in Boat 6 which, like No. 7, is not a lifeboat known to have rescued anyone from the sea. For added drama, the reporter claimed Madeleine Astor was with Eloise in the boat that pulled Robert aboard; the millionaire's bride was in Boat 4.

As with Eloise, Robert probably only met Ruth Dodge on Carpathia, where she handed a blanket to him, and the connection was exaggerated into one of dramatic survival. Robert had apparently consoled several ladies aboard Carpathia, some of whom had lost husbands. One of them, Virginia Clark, would later tell Robert's mother, when she arrived to meet him at the Cunard pier, that Robert had been "such a comfort to everybody."

For all the indication that No. 7 wasn't the lifeboat in which Robert survived, the story attracted the attention of Col. Gracie during his research for the book on Titanic that he was writing but which would only be published after he died later in 1912.

In Gracie's book, The Truth about the Titanic, Robert is listed as having gotten away in Boat 7, with no corroboration from him or any other survivor. Sadly, it's known that Gracie had planned to meet Robert during the week Gracie died. The mystery of which boat saved Robert would probably have been settled had the interview taken place.

However, while Gracie was sharp and thorough in his efforts to track down which passengers and crew went in what lifeboat, his findings aren't conclusive in several instances.

"Gracie has Steward Hart in both lifeboats 8 and 15," points out historian Don Lynch. "I'm not convinced about the Yousseff 'family' that he has in Boat 2. There is evidence that Caroline Brown was in Boat 4 and not Boat D and he has the one 'Japanese' being in Boat 13."

In Robert's case, that no one in Boat 7 remembered him being there is significant. Robert was young, rich and had socialized with a number of elite passengers on Titanic, yet no one recalled him boarding the lifeboat. The slimmest clue came from an elderly lady survivor, Lily Potter, who escaped in Boat 7. She recalled a "young man in blue silk pajamas" stepping into the boat. Unfortunately, the sighting is valueless as Robert is known to have been wearing red woolen pajamas under his bathrobe and lifebelt.

(Randy Bigham)

Even if the distinguishing color of his nightclothes wasn't known, men in pajamas, dressing gowns, bathrobes - even BVDs, according to Walter Lord in A Night to Remember - were a common sight that night on Titanic. J. Bruce Ismay is known to have worn pajamas and slippers until he returned to his cabin at some point to dress more warmly. Second-class survivor Lawrence Beesley wore a dressing gown. Margaret Brown said that, as passengers were assembling on deck, she noticed "many men" dressed "in their pajamas" Likewise, Maj. Arthur Peuchen told the Calgary Herald that men and women exhibited a grab bag of clothing choices on April 14-15, "some in pajamas, some in evening gowns."

Chapter 6: On the ship 'til the last

Moving beyond unpersuasive evidence that Robert Daniel was saved in Boat 7, arriving at a clear estimation of which lifeboat actually did save him is not as easily accomplished. All accounts published after Robert's rescue by Carpathia, deriving from interviews with him in almost every major newspaper in New York (and reprinted thereafter in papers nationwide), consistently point to one common thread: he jumped into the ocean either during or a few minutes prior to Titanic's fatal plunge, thereafter swimming to a nearby lifeboat. This is strongly supported by fellow survivors' memories that Robert was on board Titanic until the ship's last minutes afloat – accounts of fellow First Class passengers Jack Thayer and Dick Williams as well as crew members Patrick Dillion and Richard Halford.

(Michael Beatty)

But what were Robert's experiences in the hour and forty minutes between the launching of the first lifeboats and Titanic's disappearance beneath the sea?

As the first boats were going off – from the starboard side, Boats 7, 5 and 3 between 12:40 and 12:55 a.m., and from port, Boats 8 and 6 between about 1:00 and 1:10 a.m. – progress was unhurried, almost cavalier.

"One of the most remarkable features of this horrible affair," Robert would observe, "is the length of time that elapsed after the collision before the seriousness of the situation dawned on the passengers. The officers assured everybody that there was no danger, and we all had such confidence in the Titanic that it didn't occur to anybody that she might sink."

During the early period of the evacuation, Robert was on the port side of the Boat Deck, later descending to A Deck. "There was perfect order," he said. "Women were being helped into the lifeboats and there was no sign of any confusion."

Passengers' attitudes were casual, apparently receiving their cues from the ship's band, playing their instruments in the First Class Entrance, as well as the officers who "went through the ship calmly, notifying the passengers that there had been a slight accident... Capt. Smith was on the bridge and sent out orders to his subordinates as to what should be done to maintain discipline."

(National Portrait Gallery, London)

Robert witnessed the loading and lowering of Boats 8 and 6 on the forward port half of the Boat Deck before he followed the crowd aft. "I did not see any effort by any man to get on board the boats or to take the place of any of the women passengers," he told The San Francisco Examiner of April 19th.

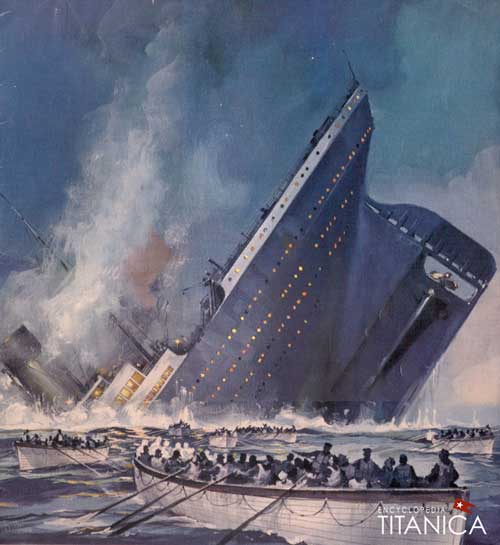

At first, Robert couldn't detect that the ship was listing. "It didn't seem to me we were sinking," he confessed to The New York Times, adding in a New York Press interview that "when the water began coming up the sides and the bow gradually settled" people moved astern.

As "the vessel began to sink slowly by the bow," Robert watched the lifeboats, one by one, "go off in the darkness." "All the time, the water was gradually creeping up," he recalled. "There was no sensation except you could see the surface of the water getting nearer to you."

The urgency of the situation became apparent as he moved with the mass of people along the deck, apparently witnessing the lowering of the aft port boats. "As the passengers got into the lifeboats – women were thrown in if they did not move fast enough – an officer jumped in to command [them] and the boats were swung free from their davits and down into the water."

Robert was by now abreast of Boat 14 as it lowered past the open promenade. It was about 1:25 a.m. and Titanic was down considerably at the bow. Nearby, panic had seized a group of male passengers, believed to be from Third Class. The men made an attempt to rush the boat and Fifth Officer Harold Lowe, in charge of No. 14, took out a gun to ward off any jumpers:

They were glaring more or less like wild beasts, ready to spring. That is why I yelled out to 'look out' and let go, bang! right along the ship's side. There was a space, I should say, of about three feet between the side of the boat and the ship's side, and as I went down I fired these shots without any intention of hurting anybody and with the positive knowledge that I did not hurt anybody. I fired, I think, three times.

(Illustrated London News)

Robert agreed he heard "several shots fired" by the officer who had "[discharged] a revolver" to "frighten others away from a lifeboat and then got in himself." His version of the event is slightly different than Lowe's but he did see the Fifth Officer because he later recognized him, an important clue to the puzzle of Robert's survival. 'There was a rush for the boats by some of the men in steerage," Robert clarified to The Washington Post, but the officer's shots successfully "drove them back." There "might have been someone shot," he would tell The New York Tribune but stressed he had "heard nothing of the sort" Even so, reporters added unfounded flourishes about men being wounded by Lowe's gunfire.

Coincidentally, Eva Hart, the little girl who had been playing with Robert's dog in the kennels for several days, was with her mother aboard Boat 14 as it descended. Like Robert, Eva well remembered the incidence of gunshots:

The officer fired his revolver into the air to let everyone see it was loaded and shouted out, 'Stand back, I say. Stand back!

(Illustrated London News)

Robert turned around on the Boat Deck at this point, walking toward the bow; whether he remained for very long on the Boat Deck when he reached the forward half isn't clear from his accounts, but he did often mention he was on the forward port promenade toward the end of the emergency when he apparently mounted to the Boat Deck again and crossed to starboard.

Although he spent most of his time forward, Robert, young and energetic, covered a lot of ground during the sinking, witnessing the loading and lowering of lifeboats on both sides of Titanic.

"Even when the passengers finally realized that the Titanic was doomed, there was no disorder," he said. "The crew's discipline was perfect and the women were placed in the boats quietly and without confusion." At about this time, Robert saw Colonel Gracie "helping women and children don life preservers."

The Washington Post claimed Robert also ran into Maj. Archie Butt and Clarence Moore either on the Boat Deck or on the promenade in the ship's final hour. He'd last seen the men at a card game in the smoking room earlier in the evening. Robert said they now seemed reconciled to the seriousness of the situation aboard.

"We'll stick until every woman is off and then we'll jump and take our chances," Robert recalled Butt telling Moore. "Maj. Butt and Clarence Moore showed themselves to be men all through. We all stood near the captain and he told us that the way we could help best was to see that no men entered the boats. That's what we did."

His own realization that the ship was in distress came by simply noting the sea rising nearer and nearer. "I kept watching the water gradually coming up to where I was," he recalled as he stood on A Deck, most likely about the time that lifeboat No. 4 was beginning to take on women and children through the glass-enclosed promenade windows which, after some delay, were finally opened to allow for loading.

By now, as Titanic was listing noticeably to port, that side of A Deck was almost level with the ocean, B and C Decks already taking on water. Robert was beginning to consider jumping and swimming out to a lifeboat, but he resisted the impulse for the time being.

(Randy Bigham)

At the moment, he found himself among a crowd of passengers lining up beside Boat 4 while it was being filled with approximately 30 women and children. After Walter Clark ensured his wife, Virginia, was safely aboard, he stood with John Jacob Astor who had also placed his wife, Madeleine, in the same boat.

As No. 4 was lowered to the sea at approximately 1:50 a.m., Robert ran over to Astor and Clark, who were "leaning against the rail talking." Robert told The New York Times he "begged them to jump overboard in the hopes of being picked up by one of the boats. They refused to leave the ship and I left them standing there."

In a syndicated story, Robert similarly claimed:

The last I saw of Col. Astor, he was standing by the rail with Walter M. Clark, Congressman Clark's nephew. I understand Col. Astor had his wife put in a boat and assured her he would follow after her.

In another interview, Robert added the further detail that the men "stood together facing the direction in which the boats had pulled off." Soon afterward, Robert approached another man of his acquaintance, Howard Case. "Howard B. Case would not leave the Titanic at all," Robert said. "I saw him helping several women into the ship's boats."

Considerably shaken up by what was happening around him, Robert thought of his dog, still below in his cabin. He never spoke directly to the press of having to leave Gamin behind, but one feels sure the dog was on his mind when Robert later told the April 19th New York Tribune that he "had a number of things in my stateroom that I would very much have liked to have saved."

From the memoir of fellow survivor Dick Williams, it's known that Robert at least claimed he did release Gamin. Williams wrote that Robert

told me that some half hour or so before the end he suddenly thought of a dog that he was bringing home with him. He went up to the top deck and opened up all the kennels. This relieved my mind quite a bit.

Of course, Gamin was in Robert's cabin that night, but after letting him out, did Robert go astern on the Boat Deck and open the kennels, too? It can never be known for sure, but if the dogs in the kennels were released, it was likely Robert who did it.

Following his mission of mercy to aid Gamin and the other dogs, it would seem Robert felt the need for some alcoholic sustenance and - either from the bar in the smoking room or the lounge - he acquired a bottle of gin. After having been on the portside most of the night and early morning, Robert came out on the forward starboard side of the Boat Deck at about 2 a.m. Exiting the First Class Entrance, he ran into shipboard friend Jack Thayer who would recount their meeting: According to Thayer, he saw Robert

come through the door out onto the deck with a full bottle of Gordon's Gin. He put it to his mouth and practically drained it. 'If ever I get out of this alive,' I thought, 'there is one man I will never see again.'

(Biography.com | The Tatler)

Thayer added that "the lights were still strong. The band, with life preservers on, was still playing. The crowd was fairly orderly."

Chapter 7: Morning of mornings

The gin had its effect on Robert as subsequent events were something of a blur to him when relating them to reporters. His state of nerves and the hypothermia from which he would suffer before the morning was over only exacerbated the problem and his memories would remain touch and go. "It is hard to realize the terrible happenings," he told The Washington Post. And to The New York Tribune of the same date (April 19th), Robert frankly admitted, "I can't tell you what happened – I hardly know myself."

At 2 a.m., lifeboat C, a canvas collapsible raft, was being lowered over the side only a few feet away from Robert and Jack Thayer who stood with his friend, Milton C. Long. In his stupor and the dim light of the Boat Deck, however, Robert thought Jack was with his father, John B. Thayer, Sr.

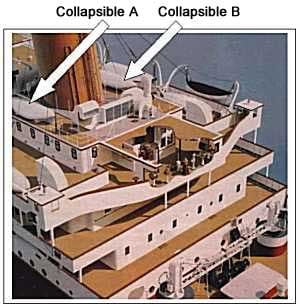

The confusion and, by some accounts, the chaos, that had transpired at Boat C had subsided, and the crew's efforts to launch the next boat, another collapsible, Boat A, began. For some 10 minutes, men tried pushing the canvas-sided craft to the edge of the deck and into the davits just vacated by Boat C. It was hard going; the deck was tilting to port so it was an uphill push.

(Murdoch.net)

After Boat D launched from the portside at 2:05 a.m., Boat A was one of only two lifeboats left aboard Titanic. According to Robert's interview in The New York Tribune, he spent an "interminable time" with Collapsible A. All the while, he was aware the rate of sinking had increased, telling the correspondent that he "felt the Titanic sinking under my feet, I could feel her going under at the bows."

The situation was growing tense and panic was brewing, but Robert and others continued toiling with what would be the last lifeboat aboard: "I did the best I could."

Meantime on the starboard side, collapsible B had landed upside down from the roof of the officers' quarters onto the flooding Boat Deck and was soon washed overboard as that side of the ship dipped under. Titanic was entering its last minutes afloat.

"Capt. Smith was the biggest hero I ever saw," Robert said. "He stood on the bridge and shouted through a megaphone, trying to make himself heard...He was still shouting when I last saw him."

In the escalating terror of the Boat Deck, as its forward portside dipped under water, Boat A had only partially been fitted into its davits. Within a few seconds, the starboard side began flooding. As water swelled up around the boat, crewmen were still trying to launch it. Robert recalled that he "managed to stay there until the deck was flush with [the] water."

Some women, already seated inside the raft and others waiting to get aboard, were washed out and away as the falls were cut at the last moment and Boat A, swamped, its canvas sides not yet fully raised, floated off the submerging deck.

As Robert's memories don't record this moment, he possibly had already headed aft with the crowd in a desperate attempt to keep clear of the invading sea. He later said he waited until he thought most women were off the ship or, as he put it, "until I had done everything that I could do." He reasoned that "it was better to jump than remain on board and be drowned like rats in a trap."

The New York Times claimed that in his excitement, running ahead of the water surging up the deck, that Robert thought he saw First Officer William Murdoch commit suicide with a bullet to the brain. But this cannot be substantiated. It is almost certainly either an exaggeration of an incident that transpired or else was a complete press fabrication in keeping with its notorious sensationalism in the aftermath of the disaster.

(The Sphere)

Robert was still near Thayer and Long on the starboard Boat Deck, moving aft. They stopped to jump, but Robert kept running:

It looked to me as though his father [sic] pushed him off and jumped after him, but the boat sank so soon afterwards and things were so mixed up that I couldn't be sure about that.

He also passed Dick Williams, wearing a full -length fur coat, and his father, Duane. Robert said it was "one of the saddest cases I saw," adding that "he [Williams] and his father both jumped but the father was not saved."

As he ran, the ship was settling and Robert could hear a "frightful grinding noise," a "horrible grinding and knocking." Although he couldn't have known it at the time, Titanic was beginning to break apart between the third and fourth funnels. The Boat Deck was awash to almost the point of the first funnel yet Robert could still hear the band playing; he might have noticed "Nearer, My God, To Thee" as he later said he couldn't stand hearing the hymn played.

Reaching the "rear of the deck" - apparently the end of the Boat Deck - Robert climbed over the rail and dropped to the deck below. There, or just before he jumped to A Deck, he claimed he encountered Isidor and Ida Straus whom he noted were standing arm-in-arm and debating whether to get into a lifeboat, a fruitless argument since, as Robert noted, the "last lifeboat had gone and the Titanic was sinking fast"

(Straus Historical Society)

He stressed in another interview that "the lifeboats had been filled and lowered and there was no way to escape, save by jumping." But when and where would he jump? Delaying the inevitable decision, Robert seemed intent only on getting to the highest point of the rising stern.

"With many others I mounted from deck to deck as the ship settled," Robert said. He dropped from A to B Deck and finally to the aft Well Deck which he crossed to climb a flight of steps to the Poop Deck, the very stern of Titanic.

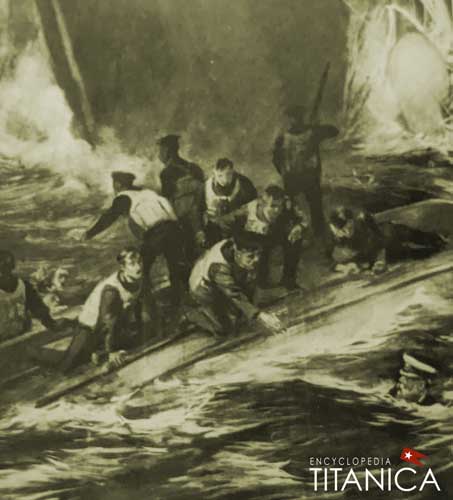

This section was crowded with people and he soon joined a group of crewmen who were smoking cigarettes. Two of these were engine room crewmembers, Thomas Patrick "Paddy" Dillon, a trimmer, and John Bannon, a greaser. A third man in the group was Third Class Steward Richard Halford.

'The Poop Deck was full of Third Class male passengers," recalled Dillon who was a little tipsy, having downed several tumblers of whiskey in the "first cabin bar room" where Robert may have just been, too.

Surrounded by other stewards, deck hands and Third Class men and women, the group tried to avoid the mass of panicked humanity that was thronging the Well and Poop decks.

There "seemed to be thousands fighting and shouting in the dark," Robert remembered. "Everybody seemed to have gone insane. Men and women fought, bit and scratched."

(Gregg Jasper)

In the scramble, Robert suffered a 'black eye and cut chin." These "wounds upon his face" were "marks of battle" later noticed by the press in his interviews.

Robert was standing on the Poop Deck when the "lights went out," plunging the ship into total blackness. This was followed by the ship's complete break up amidships which sent Titanic's forward half diving below the sea while the stern dropped back on almost even keel. Paddy Dillon recalled:

Then she plunged and then seemed to right herself. There was about 15 of us when she took the first plunge. After the second, there was only five of us left. One of these was a Mr. Daniels [sic], a First Class passenger. He only had a pair of knickers, a singlet and a blanket thrown over his shoulders. I think he jumped for it.

As the stern slowly tilted up again, Robert noticed "men praying as I struggled to get to the rail. Curses and prayers filled the air."

To The New York Tribune, Robert recounted:

I grabbed something and uttered one prayer. Then I went over the side of the boat. I tried to wait but suddenly found myself leaping from the rail, away up in the air and it felt an eternity before I hit the water. "

To The New York Press, he explained:

I thought it was time to jump and I plunged overboard... The sea was many scores of feet below us."

(Daily Sketch)

He was likely not as high above the water as he thought, but in the pitch dark, plummeting into the sea from any height would've seemed a nightmare. "There was no rope with which I could lower myself over the side so I risked all in a dive, feet foremost," he added.

To Robert, it appeared that there were "at least a hundred men who jumped when I did. I saw several going over the rail but after that, I saw them no more."

He estimated that he jumped "just five minutes before the Titanic sank," although it may have taken less time for the mammoth stern, rotating over the site where the bow went down, to disappear beneath the waves. Although Robert "feared the suction would drag me down," he found there "was no suction."

Of the men who'd been with Robert a few minutes earlier, Paddy Dillon and Richard Halford also survived. John Bannon would make it alive into the water but died of hypothermia as did most of the other nearly 1,500 people aboard Titanic when it sank at 2:20 a.m., April 15.

Dillon, disoriented by whiskey and exposure, was hauled aboard Boat 4, floating nearby. Halford, as The New York Call reported on April 20th, "was with Robert W. Daniel on the poop deck when the ship foundered and both floated about for some time before being rescued." Another paper claimed Halford had escaped in lifeboat No. 5, a near impossibility for a Third Class steward, while some later researchers believed Halford may have left in an aft starboard lifeboat. Yet he claimed in his first interview that he swam to a boat.

Chapter 8: Picked up from the sea

Which lifeboat picked up Halford isn't known any more than which boat saved Robert but, in the latter case, there are at least clues that narrow the possibilities. By the time the ship sank, nearly all lifeboats had cleared the side of Titanic by several hundred feet, most by hundreds of yards, one, perhaps, by half a mile to a mile. Only the last two collapsibles, floating free of the liner as it went under, were in the immediate vicinity: Boat A, swamped, and B, upside down. In addition, Boats 4, C, D and 10 were relatively nearby, having been the last boats lowered.

However, most of these can be eliminated as having rescued Robert. There was but one verifiable instance of a man being hauled aboard Boat D from the water - Frederick Hoyt whose wife, Jane, was already in the boat. The New York Sun did say Robert was taken onto Boat C, in which J. Bruce Ismay had escaped, but, since this claim wasn't made elsewhere and no other survivor account exists of any swimmer being taken aboard, it can be discounted as almost certainly a tabloid-worthy fabrication.

Boat 10 can probably also be excluded as saving Robert; no account from a survivor in that boat described an instance of a swimmer being rescued. Second Class passenger Lillian Bentham (in No. 12) did claim an intoxicated "man in evening clothes" was transferred into her boat from another but, considering her account was relayed through a family member and was thereafter seemingly manipulated for dramatic effect by the press, it cannot be relied upon.

(Randy Bigham)

The possibility that Boat B rescued Robert may be rejected, too. The accounts of the men who survived aboard this boat are numerous, and none of the stories – including those of Second Officer Herbert Lightoller, Col. Archibald Gracie, Junior Wireless Operator Harold Bride and Jack Thayer – make mention of the young banker in red pajamas, his bathrobe and blanket having been lost in swimming.

Although in one of his most widely read 1912 accounts of the disaster - included in the book Sinking of the Titanic by Jay Henry Mowbray - Robert was quoted as saying he was saved by Boat B, the claim doesn't stand scrutiny. "I clung to the same overturned lifeboat that young John B. Thayer, Jr., swam to later" was the brief comment attributed to Robert.

Yet in no other report, even in his lengthiest interviews, did Robert make this assertion again, if indeed he made it in the first place. Although he admitted to The New York Press of April 19th that in Titanic's last moments "J. B Thayer Jr. of Philadelphia" was with him until he "got away from me" Robert never said any more about him.

If it's true that Robert made the statement at all, he may have based his contention on learning aboard Carpathia that Thayer survived on a collapsible boat and merely assumed it had been the same one he'd also made it to. Even so, Robert never used the terms "upside down" or "overturned" to describe the boat that rescued him in any other known account. He did, however, often use the word "collapsible."

(Michael Beatty)

At first glance, this would appear to be the most obvious clue to which lifeboat Robert managed to swim. He told The New York Tribune it was a collapsible that plucked him from the ocean and he communicated the same to his mother after his rescue.

Another clue was supplied when Robert elaborated that he was "picked up by one of the boats I had helped to load and get away from the Titanic." He had indeed assisted with getting Collapsible A prepared for loading. Was this the boat that rescued Robert? It didn't capsize but it was swamped as it was being prepared for launching on the plunging Boat Deck. Even his friend Jack Thayer guessed that "he [Robert] apparently fought his way into one of the last two boats." If Robert wasn't aboard B, might he have been in A?

The situation that Boat A faced in Titanic's final minutes afloat was without question the most heartbreakingly tragic of all rescue attempts on April 15. The boat was almost dragged under with the sinking ship, was released from its fall lines only at the last second, rose on the crest of the wave that rolled along the Boat Deck, and spilled its occupants of women and children into the churning sea.

Passengers and crew who managed to get back into the collapsible as it drifted off, or who swam to it later, had to stand in the freezing water that flooded the boat. Most of the men and women who clambered aboard did not survive the prolonged exposure, their bodies floating away or remaining in the bottom of the boat.

Yet the horror of this Robert never recalled. The effects of hypothermia may well be the cause of the lapse in memory which he claimed gripped him that morning when he apparently lost consciousness once pulled aboard whichever lifeboat saved him.

(Illustrated London News)

He tried to recall his immersion in the sea and his rescue to the many reporters with whom he spoke following Carpathia's arrival with Titanic's survivors in New York, but details were patchy and only now have they been pieced together in an attempt to arrive at some conclusion.

Titanic's stern, from which Robert jumped, had not quite disappeared when he first came to the surface.

"The shock was fearful," he said. "I realized I could survive only by getting my blood into good circulation and I lashed the water in an effort to get away from the Titanic." He similarly explained to another reporter that he felt he had a chance to make it, "knowing I was a good swimmer and could keep up until the exposure got too great."

The "minute he struck the water he began to swim," one paper wrote. Another quoted him as saying, "My God, to listen to the screams that I heard…was a terrible experience"

Robert's niece Helen Daniel Rodman was always moved by her knowledge of what her uncle had suffered through in those final moments on the doomed ship. "It is clear that he deported himself well on that terrible night and jumped into the icy water only at the last moment," she maintained. Robert seldom spoke of the experience which prompted Helen to write many years later to A Night to Remember author Walter Lord, asking his opinion of her uncle's mode of rescue. Lord believed, like Thayer, that Robert survived in one of the last lifeboats. Eventually, following her own search through newspaper archives, Helen came to share this opinion. She believed Robert was rescued by Collapsible A, which also saved his acquaintance, Dick Williams.

Just before Titanic disappeared, the cries of those dying in the water filling Robert's ears, he could see the stern taking its final dive with a "throng of insane, struggling persons at the rail" As he swam, he "saw boats near" but was growing so weak from the "killingly cold" water that he "almost gave up."

(Randy Bigham)

Although his (or reporters') estimation of how long he was in the water varied from two to as many as five hours, in reality hypothermia kills well before that. His admission to The New York Sun that he was "in the water some 15 or 20 minutes before I was picked up" is the closest to facts known today about the survivability of the condition.

According to studies, loss of dexterity in people not dressed in protective clothing occurs within two minutes of being submerged in water 32° or colder. Exhaustion and unconsciousness occur at up to 15 minutes in these temperatures and people immersed in freezing water aren't expected to survive for much more than 30 minutes. The physical and mental shock of being immersed, called "cold shock,' can cause cardiac arrest as can subsequent hyperventilation. As blood moves away from the extremities, it congeals in the muscles. Unfortunately, consuming alcohol, as Robert and others had done just prior to the sinking, increases the danger for those subjected to hypothermia; alcohol decreases the body's ability to generate heat through shivering and it increases blood-flow to the skin. This causes sufferers to feel warm, and they sometimes experience "paradoxical undressing" whereby they remove their clothing even though they're freezing to death.

Laboratory tests on rats have shown that cold water-induced hypothermia impairs learning capacity as well as memory retrieval in a way similar to those afflicted by dementia: as such, it's unlikely that Robert would have been able to remember very much of his ordeal.

"For those who remained in the water or could not be helped once pulled into a boat," registered nurse Lynne Francis has said, "their breathing became slower and shallower and their heart rate continued to slow, beating ever more irregularly. The lack of oxygenated blood to the brain stem would lead to respiratory suppression – slow and ineffective breathing – which would inevitably result in cardiac arrest."

Licensed practical nurse Julian Whited further explained:

Once shivering ceases, it's a sign the condition is getting worse. Someone with hypothermia usually isn't aware of his or her condition because the symptoms begin gradually. Also, the confused thinking associated with hypothermia prevents self-awareness. It should be noted that a variety of factors can also contribute to the way that an individual experiences hypothermia and its aftereffects, such as their state of health at the time, consumption of alcohol, and comorbidities.

Before shock to his system overtook Robert and he "became unconscious" aboard the boat that he was pulled into, his mind was on swimming to avoid being "drawn in by the suction" of Titanic as it sank. He was amazed to find that "when the ship went down, the suction was hardly perceptible and I did not have any trouble from the vortex."

He also repeatedly told reporters the detail that he was only half-dressed as he swam that morning, saying to The Baltimore Sun that he was "picked up naked from the ice-cold water and almost perished from exposure" before being rescued." He stressed to The New York Tribune that "I was naked" which he later amended to "almost naked" when interviewed again for the same paper.

(Randy Bigham)

It's known from accounts by others – Paddy Dillon and Carpathia's Dr. Lengyel – that Robert was not actually nude. He was in red pajamas which had apparently become torn while swimming. During this exertion, Robert also "lost his bathrobe," according to The Washington Post of April 22nd, a statement confirmed the same day by his hometown paper, The Richmond Times-Dispatch.

Thrashing nearby was Robert's friend Dick Williams whom he had last seen jump with his father from Titanic. Williams had spotted Collapsible A and struck out for the boat. He recalled:

As I was in the water, swimming towards the collapsible lifeboat, I thought I saw the small black face of a French bulldog which was evidently swimming in my general direction. At the time, I thought I must be seeing things…

He recalled Robert assuring him on Carpathia that there indeed "was a black faced French bulldog" aboard, his beloved Gamin de Pycombe. Williams concluded that "the poor little fellow was evidently doing all he could to get out of this unexpected situation, just like the rest of us."

Robert didn't see Williams or Gamin in the water near him, but it seems possible that the boat he climbed onto was the same that Williams pulled himself aboard, although this can never be determined absolutely.

In Robert's New York interviews, apart from claiming the lifeboat that saved him was a collapsible and that he had earlier helped to load it, all he ever said of the boat that picked him up was that it was "floating a few feet from the sinking ship," and that he got in it "shortly after the Titanic went down."

He said he caught

hold of the stern and pulled myself aboard. I was trembling as if I had been a leaf in a storm… I had no right to ask to be picked up but I was picked up."

The other important clue that narrows the prospects is that Robert said he recognized the officer who was in command of the lifeboat that rescued him. He insisted it was the same officer who had fired gunshots aboard Titanic to deter steerage men from rushing the boats. "I saw him afterward in the very lifeboat that picked me up," he told The New York Times of April 20th. It will be remembered that this was Fifth Officer Lowe.

(Henry Aldridge & Son Ltd Auctions)

It might not have been Boat 14, however, that initially saved Robert – the three or four men whom Lowe rescued when he took No. 14 back to the wreck site are mostly accounted for. But Robert may have ultimately been transferred to 14 from the unknown boat that pulled him from the sea. It so happened that Lowe was in charge of a flotilla, consisting of Boats 10, 12 and 4 and Collapsible D. Lowe ended up towing Boat D as it was leaking; its passengers' screams for help had caught his attention in the hour just before dawn.

After throwing a tow line to D, Lowe heard more people yelling; this time, the voices were coming from swamped Collapsible A. He rowed his fleet of boats over to A, hauling the dozen or so waterlogged survivors into No. 14.

Robert may have been among those lifted from A into Lowe's boat or he may have already been aboard another lifeboat in the fifth officer's little armada: Boat 4. The only other boat that could have saved Robert from the water, No. 4 also rescued Paddy Dillion, his inebriated companion on Titanic's stern.

Other than Boat A, Boat 4 is probably the only feasible possibility for rescuing Robert in the first few minutes after Titanic sank. As previously stated, the other lifeboats nearby at the time – Boats B, C, D and 10 – aren't likely candidates.

But Boat 4, lowered 30 minutes before Titanic went down, remained close to the ship, taking aboard eight to 10 crewmembers who descended fall lines into the lifeboat or swam to it before and after the ship sank. While Robert later described a collapsible, might he have misremembered that detail in his hypothermic, drunken condition?

(Philip Weiss Auctions)

Interestingly, he claimed that all those in the boat that found him were women, telling The New York Press, as well as specifying to The New York Sun, that there were 34 "women and children" aboard; to The New York World he said there were "37 persons" in the boat. That doesn't sound like A; there was only one woman saved from Boat A (Rhoda Abbott), although Dick Williams remembered there were three women originally, the others possibly being First Class ladies Edith Evans and Anne Eliza (Lizzy) Isham who died before rescue came. On the other hand, Boat 4 contained about 30 women and children, a number which matches more closely Robert's memories. It's also known that, as with A, Robert had been on hand when Boat 4 was loaded and launched.

In the final analysis, it's obvious Robert's escape from Titanic was not as it was previously imagined by some – a comparatively leisurely jaunt in the first lifeboat that departed the ship. It was by jumping at the last terrifying minute and swimming to a nearby lifeboat – apparently either Collapsible A or Boat 4 - that Robert survived. It can never be known conclusively which of the two boats it was or if, indeed, it was yet another boat. But beyond that, the harrowing nature of Robert Daniel's experiences aboard ship and afterward can now at least be understood to the fullest extent possible.

Chapter 9: Recovery from exposure

Robert had almost no memory of the dawn of April 15 as Carpathia loomed over the horizon and Officer Lowe struck out for the rescue ship, his lifeboat's complement now including the survivors of Collapsible A. Collapsible D remained in tow, but the other boats had cut loose from No. 14, each rowing independently to Carpathia.

(Michael Beatty)

Exhausted from swimming and hypothermia, Robert had passed out soon after being saved by either Boat A or Boat 4. Whether he was in 4 or was now with Lowe in 14, Robert recalled seeing the outline and lights of Carpathia.

"It seemed a long time before we saw the masts of the Carpathia, but when the straight masts and the blur of smoke from her funnels were outlined against the horizon, we realized that it meant rescue for all of us," he said. When his lifeboat reached the ship, he explained that "the men in the boat did what they could to help the women to the vessel, but most of us were almost helpless from the cold and exposure."

Apparently, Robert fell unconscious again by the time whichever boat he was aboard reached the side of the rescue ship – if it was Boat 14, he arrived at Carpathia at about 7:15 a.m.; if it was Boat 4, he made it in around 8 a.m. "Somehow he was hauled up," his mother later related, adding that the crew of the Cunarder mistook Robert for a Third Class passenger and "put him in the steerage in a bunk with a sailor."

This seems to have been the case as he received medical attention from Dr. Lengyel who was assigned to aid Titanic's Third Class survivors. According to Lengyel, Robert "was delirious" as well as half-clothed so he "gave him [Robert] my own suit." In a speech he presented later, Lengyel expounded on Robert's condition, writing that he wore a "torn, red nightshirt" and "kept insisting he was a doctor." Lengyel explained that

I didn't want a colleague to be left without clothes so I gave him mine. When I talked to him on the next day, he couldn't recall that. Probably in his delirium, he gave an incorrect profession to me.

(Lengyel family | Kalman Tanito)

Robert's mother, Hallie Williams Daniel, further related what her son subsequently told her:

Several hours later, when he had recovered from the shock, he explained that he was a first cabin passenger and he was removed.

He was transferred to Carpathia's First Class section but it's doubtful he was first moved to Captain Arthur Rostron's private cabin, as his mother claimed. He continued to receive "medical attention" in the First Class physician's quarters and

was in there for a while with J. Bruce Ismay. Robert says the feeling toward Ismay was very severe. Ismay sent for Robert to ask if he had been criticized and finding the true sentiment, the managing director remained in his stateroom. After that Robert slept on the floor.

That, too, was confirmed in an interview with a reporter for The New York Sun whom Robert told he "had slept on the floor of the dining saloon."

Robert soon revived sufficiently to no longer require the doctor's help and he began mingling with fellow survivors. One thing he didn't do was assist with Carpathia's wireless transmissions as several newspapers would later claim.

When Helen Daniel Rodman, Robert's niece, contacted Walter Lord to ask him about these claims in the press, Lord responded in a letter dated July 14, 1992:

Whatever the circumstances of his leaving the Titanic, I do not believe he helped with the wireless on the Carpathia. He is not mentioned in any of the accounts by Harold Cottam, the Carpathia's operator, nor by Harold Bride, the Titanic's assistant operator who pitched in to help Cottam. I think he would have been mentioned had he participated, for the Senate went very deeply into the question of the Carpathia's slow service in handling wireless communications. The Cunard Line made every effort to show the Senate investigators that they tried everything possible to speed up the service, and that would include mention of any help given by Mr. Daniel.

(The Sphere)

That Robert spoke aboard Carpathia with Bride is evident from his interviews, however. Bride told Robert, for instance, of the Frankfurt being 35 miles away while Titanic was sinking.

"Phillips' assistant on the Titanic told me he and Philips had a fight with some sailors who wanted to take away their life preservers," Robert also said, referring to Jack Phillips, Titanic's chief Marconi operator; it was a story related by Bride himself in a New York Times interview.

Making the rounds of fellow survivors, Robert encountered a group of widows whom he estimated were all under 23 years of age "sitting together on deck;" he recalled this as a "pathetic incident" among the many he witnessed. Another sad sight was that of "nine bodies buried from the Carpathia." There were actually only four buried at sea, according to Carpathia's Capt. Rostron.

He ran into Jack Thayer who "told me his father was sucked down" with the ship, and Dick Williams who informed him his father, too, had been lost.

Robert also met with some of the Titanic's surviving officers who told him the ship "tore her bottom out" on the iceberg. To which officers he spoke, Robert didn't say, but apart from Second Officer Lightoller, the others aboard were Third Officer Pitman, Fourth Officer Boxhall and Fifth Officer Lowe.

Others he remembered meeting were Ruth Dodge and her son, Washington, Dodge, Jr., although reporters later confused his meeting her on Carpathia with having shared the same lifeboat with her. Ruth and son were "bundled up amidships" and "reclining on a pillow" and Robert recalled "she passed me a blanket."

(Los Angeles Times)

He tried comforting some of the widowed survivors, including Virginia Clark who would later assure his mother that he was safe when they met at the pier in New York as Mrs. Daniel and other family members were looking for Robert. And he soon introduced himself to Eloise Smith whom he would marry two years later.

Robert soon met up again with Col. Gracie on Carpathia and by the time the ship reached shore they "had become fast friends."

One survivor he didn't see on board but heard much about was Madeleine Astor. He said he knew she was being cared for by a doctor and "occupied a cabin given her by one of the passengers on the Carpathia." Reportedly, she went first to Captain Rostron's stateroom and then to Charles and Josephine Marshall's cabin.

(Daily Mirror)

He met and talked to many other survivors, but Robert never met the young English girl who, unbeknownst to him, had taken such a fancy to Gamin de Pycombe aboard Titanic. Eva Hart and her mother had escaped in Boat 14, into which Robert may have been rescued from Collapsible A. Eva mourned the loss of her father, Benjamin, but also little Gamin with whom she said "I had fallen in love." Eva later wrote:

After the ship had sunk and we returned to England, I longed and longed for a little dog like that, but when I described it to people, I couldn't find anyone who knew what type of dog it was. As a result, it wasn't until 1955 that I discovered the breed. A year later I was given one as a present and at long last had the pleasure of owning such an affectionate animal. The beautiful French Bulldog I eventually owned was the image of the one I had played with many years previously on the Titanic."

Carpathia reached New York Harbor on Tuesday night, April 18th. His mother, Hallie Daniel, and a cousin, John Skelton Williams, eagerly awaited Robert at Cunard's crowded Pier 54; Mrs. Daniel knew he had survived as she had received a cable from him on April 16th, saying, "I am safe."

Although he was still weak, the newspaper reporters who thronged the dock claimed he carried Eloise Smith, who was said to be in a "fainting condition," down the gangway. Robert was actually "one of the first to appear on the gangway of the steamer," according to The New York Tribune. Exhausted, Robert released Eloise to her father, Congressman Hughes, who ran up to greet her.

Robert wore a tattered Derby that he had borrowed from someone on Carpathia. And when he came down the gangway, he looked to his mother "terribly drawn" in the face, so much so that she "hardly recognized" him. She couldn't speak immediately with him because he was "flanked by reporters" asking questions. She described his appearance as distressing, Robert wearing "a pair of trousers large enough for a giant, a blue shirt he had bought from the Carpathia's barber and he had no coat, only an old shawl."

(Library of Congress)

"Every one of the persons rescued was on the open sea for hours," Robert informed the press men who surrounded him. "We had not a bite to eat. The wind coming over the sea of ice and great bergs chilled us to the marrow of our bones."

Robert looked "almost a total wreck" and was "so weak he could hardly stand," as The New York Sun wrote while other papers noted his cut and bruised face. The questions flew fast from the men and Robert was soon overwhelmed. At one point he "reeled" and was caught by reporters.

"At this time, Mr. Daniel was so overcome that he had to be led to a rail where he rested himself for a few moments," explained the Tribune. "Let me smoke a cigarette before we go on," he said.

He was asked about gunfire aboard, denied Archie Butt shot anyone or that Captain Smith shot himself, as had been rumored, yet was quoted as having seen First Officer Murdoch commit suicide, a questionable claim likely manufactured by a press anxious to dramatize events.

He told reporters he was "fighting for my life when I was rescued," and that the grieving condition of survivors on Carpathia was "horrible."

Inundated by reporters, Robert was also sought out by relatives of victims seeking information about their loved ones, including Vincent Astor, John Jacob Astor's son, and a man who said he was Percival White's brother.

(Father Francis Browne Collection)

Many of the questions flung at Robert had to do with Ismay.

"I will not discuss anything about Ismay," he finally said. "I saw him on the boat but I did not see him after we boarded the Carpathia. I have no comment to make on what he did or is reported to have done. Ismay just kept to his stateroom. He apparently did not concern himself about anyone."

Yet when speaking to other reporters, he contradicted his claims not to have spoken to Ismay on the rescue ship. "What Mr. Ismay said to me, I must treat as confidential," he told The New York World. "Any statement he cares to make must come from him personally."

And to the Sun he admitted Ismay was "terribly cut up," meaning emotionally.

Robert wanted to leave the pier but his mother convinced him to stay to answer a few more questions from reporters who "literally held him up while he was talking." Finally he left for the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel.

He was glad to get away from the press, to rest from the ordeal of the disaster and its aftermath. In a few days, he seemed mentally improved but his recovery from the exposure he'd suffered took longer. A month later, as one newspaper reported, Robert was still under medical supervision when he took a vacation to Georgia:

Robert Daniel of Richmond and Philadelphia who was among those rescued from the Titanic has come to the Warm Springs Hotel to spend the early part of the summer. He is suffering from nervous shock and is under the care of a physician.

While Robert was healing from his ordeal, he was still suffering. A letter he sent to Dr. Lengyel, who had cared for him on Carpathia, shows his emotion and deep gratitude yet he made no direct reference to Titanic. "You have been much in my thoughts during the last two months," he wrote on July 11, 1912, adding, "I hope you understand how deeply I appreciate your kindness and attention to me when we first met." On Shillard-Smith, Daniel & Co letterhead, Robert assured Lengyel he'd "carefully put away your suit" which he hoped to return to the doctor soon as well as meet him again if he was able to visit Budapest.

(The Truth About the Titanic)

Robert was on the mend by the end of the year and resumed overseas business trips. But the death of his friend, Col. Gracie, in December, brought back the horror of Titanic. When he returned from abroad early that month, he hadn't heard of Gracie's passing and when asked by a reporter about him, Robert replied, "I have a letter here from him, asking me to be sure to see him on my return from England," adding, "I shall get up to see him today." When informed Gracie had died the previous Wednesday, Robert was "overcome with grief" and declined to talk anymore.

Chapter 10: Later life and death

"After the Titanic disaster, he felt like he should have been dead, so he saw his remaining time as a second chance at life," Robert's daughter-in-law, Linda Daniel, said of his years following the sinking.

Whereas before he had been frugal with his money, Robert began enjoying it, purchasing luxury items like racehorses and a yacht (in which he used to cruise the Potomac River). He also took up card playing with a passion and avidly played the stock market.

Early in the spring of 1914, Robert was returning from his country home in Richmond to his primary residence in Philadelphia. He was asked by a friend to spend an evening in Washington, D.C. as a guest at an informal dinner dance and he accepted the offer.

Robert was to escort a Mrs. Smith, the hostess informed him. He found that the lady was none other than Eloise Smith, the young widow whom he'd met aboard Carpathia and had accompanied down the gangway when Titanic's rescue ship docked on April 18th. That evening dance was the kindling of a remarkable romance that would culminate in the only marriage between Titanic survivors who weren't linked in some way prior to the disaster.

(Betsy Smith McLain)

Robert continued to call on the 19-year-old, much to the chagrin of her father, Congressman James Anthony Hughes, who felt it was unwise for Eloise to become involved with another man while her relationship with her late husband's family remained so tense; Eloise had filed suit against her mother-in-law in an effort to gain more of her late husband's estate for her son, Lucian Philip Smith II, with whom she'd been pregnant aboard Titanic.

There may have also been a tinge of political dissent; Robert was a confirmed Democrat, whereas Congressman Hughes was a staunch Republican.

Despite her father's protests, Eloise ultimately wed Robert in a small, hushed ceremony on August 18, 1914, in the Church of the Transfiguration in New York City. Very soon after the ceremony, Robert again journeyed across the sea that he knew all too well - to attend to business in London. Historically bad timing left him marooned in England while World War I erupted.

Speaking to The Richmond Times-Dispatch of October 27, 1914, Robert broke the silence regarding his marriage:

On August 18, Mrs. Smith and I were married in New York. The following day I was compelled to sail for London on urgent business. Owing to the war, I considered that it would be difficult to care for Mrs. Daniel abroad, so I left her in this country. It was my intention to return within three weeks, but I was held up more than two months. My hurried departure prevented us from making a formal announcement of our wedding, and we are making plans to make it tomorrow. Our intimate friends have known of the wedding, so it will not be a surprise to them.

(Betsy Smith McLain)

Eloise, little Lucian, and Robert settled in Rosemont, an upscale suburb of Philadelphia where fellow First Class Titanic survivor William Carter also resided. The Daniels were at least socially acquainted with the Carter family; in 1920, Robert signed for verification Lucile Carter's passport application. The Daniels also kept a home in Richmond.

By this time, Robert had replaced Gamin de Pycombe with another bulldog, this one of the English breed. It was noted in March 1915 that the dog took the blue ribbon in a Philadelphia dog show.

Inevitably, the United States was drawn into what was optimistically referred to as The War to End All Wars. On April 6, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson officially declared war on Germany.

Both Eloise and Robert took measures to actively serve their country during the ensuing conflict. In December 1917, Robert helped to organize a battalion for home guard defense at Bryn Mawr and Rosemont. The group held several sham-battles with other battalions, with the new Major Daniel's men winning many victories. Meanwhile, Eloise undertook training as a nurse.

In February 1919, Robert, now Captain Daniel, was sent to France by the War Department as custodian of money to be used in exchanging French currency carried by returning soldiers. He came back to the US in March aboard Mauretania. On May 3 of that year, Robert and Brigadier General Herbert Lord were presented with Treasury Department medals for their distinguished services.

(Betsy Smith McLain)