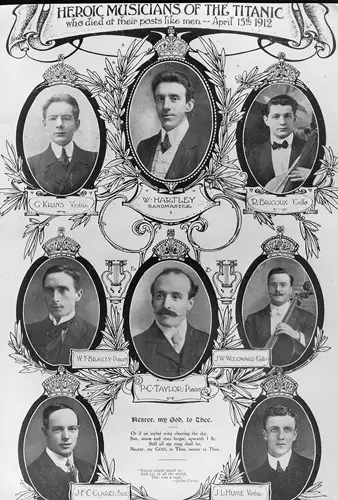

Most people, when thinking about music on the Titanic, immediately recall Nearer My God to Thee, which was allegedly played on deck by Wallace Hartley and his band as the great ship sank. We do not really know if this is true, and even if it were, we are not sure which of the tunes to which this hymn has been set was played in the early hours of April 15th 1912. There are two main contenders – Bethany and Horbury, both equally affecting. Filmmakers have veered between both. Bethany, here sung by the great Irish tenor Jack McCormack in 1913, was chosen in 1943, 1953 and 1997, whereas Horbury was favoured in A Night to Remember in 1958. The lyrics, however, inspired several other musical settings, including one by Arthur Sullivan (of Gilbert & Sullivan fame). But Wallace Hartley, a Methodist, who was known to love the hymn, would probably have been most familiar with Horbury. The lyrics were, however, written by a woman.

Ladies liked writing hymns in the 19th century. Nearer My God to Thee was written by Sarah Flower Adams in 1841, and was first set to music by her composer sister, Eliza Flower. Other famous hymns written by women include All Things Bright and Beautiful by Cecile Frances Alexander, who also wrote There is a Green Hill Far Away and Once in Royal David’s City. The poet, Christina Rosetti, pursued her somewhat glum outlook on life with In the Bleak Midwinter; Jane Montgomery Campbell was rather more upbeat with We Plough the Fields and Scatter. The American Fanny Crosby reputedly penned 8,000 hymns, which seems hard to believe, especially when you consider that someone else had to write the tunes. In fact, it is hard to see how the 19th century Protestant and Non-Conformist USA churches, which have so inspired other forms of music, such as American Gospel, the Blues, and even early rock, would have become such uplifting and lyrical comforters of the spirit without all those women – many of whom were the kin of bishops, vicars, ministers, and pastors. One can imagine the scene: “If you’ve finished your sewing, my dear, you could write a hymn to the glory of the Lord. Instead of just gossiping ...”

So it is possible that Wallace Hartley and his musicians watched the women leave the ship, musically expressing what faith and comfort they could muster for the doomed men and themselves, while evoking the words of a woman. Irony, indeed.

But before the disaster and the final hours, the music on board would have been very different.

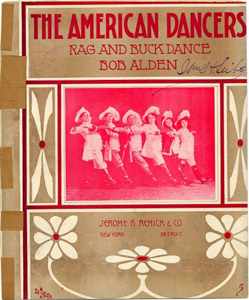

By 1912, music was definitely becoming rather more adventurous. Not because that in itself was new - it most certainly was not - but because it was becoming more widely distributed in a comparatively shorter time. Communications were improving because more people were travelling, and in an era before phonographs were widespread, sheet music and making your own entertainment was ubiquitous. And the covers of sheet music could be as alluring to them as are music videos to us now.

From 1910 (University of Southern Carolina archive)

Then, as now, people wanted the latest thing, from either side of the Atlantic and, since Britain and the USA shared a common language, they also shared music.

Queen Victoria had been dead for over ten years and, on both sides of the Atlantic, the masses revelled in variety and music hall (vaudeville), and sheet music made it available for home consumption - no doubt to the disapproval of the older generation. Raffishness, in general, had been pioneered by the next British King – Edward VII (1841-1910), known also as Bertie, who was well-known as a “player”. His son, George V - the King from 1910, was definitely not, being more interested in his stamp collection and the fiancée he “inherited” from his deceased older brother, Albert. This was his wife, Queen Mary (Princess May of Tec). She acquiesced in this arrangement. Strange times.

But his subjects were still in thrall to the “naughty 90s”, so music was not entirely respectable, and it could be fun.

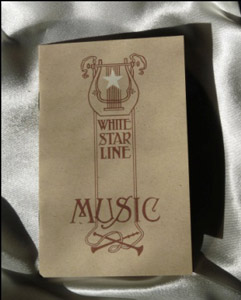

Wallace Hartley and his band were constrained by the official White Star Line repertoire, which was necessarily tasteful, and famously depended on the musicians knowing pieces by heart, so that when Hartley said “No. 124!” they all instantly struck up. It is said that there were over 200 numbers in the White Star Song Book, but that makes it seem rather unlikely that the musicians used them all on one voyage.

Even if they all had perfect pitch and could play by ear, like buskers, you would think it rather unlikely that they would subject themselves to such a regimen. It seems more likely that they would have used a smaller repertoire of music, and rotated it over a voyage which lasted only about a week. However, this may be wrong, and it is possible that the musicians could, indeed, strike up any song when requested. The White Star Line issued a small pocket-sized booklet for passengers, of nine pages, from which it was possible to make requests by number. “No. 125, please!” In which case, the musicians certainly earned their money. Here, Rebekah Maxner discusses both the White Star Line songbook, and the sort of music played. She likens it to a modern karaoke menu. Much of the music is less known to us now, but was popular then, including composers such as Aubert, Suppé, and Flotou. Franz von Suppé is best known for the Poet & Peasant, though it doesn’t seem particularly suitable for a small orchestra on the Titanic.

The better-known today from the White Star Line songbook includes Rossini. A man who never knew quite when to finish a musical work (The Barber of Seville - 6.20 minutes, for the impatient who want to experience this prolonged finale). And here is Maria Callas, singing from Bizet’s Carmen, another great favourite song, though not at the time sung by her, of course.

Elsewhere on the ship, it is clear that making your own music was encouraged. There were two grand pianos in first class on the Titanic and several uprights elsewhere, one of which is known to have been in third class, probably two in second class, and possibly another in first class. With the number of passengers on the Titanic, there would not have been a problem in finding people who could play the piano. The wealthier would have had expensive music lessons, but 3rd class might have learned by ear, and trial and error. It has been suggested that the expense of a piano was too great for ordinary workers, but it was an aspirational luxury, and there were many financial schemes to allow the masses to buy an inexpensive piano to grace the parlour. I have one myself, but without the candelabra which adorned the one of my childhood.

However, there were many more portable musical instruments that passengers probably brought on board with them. Concertinas, mouth organs, fiddles, pipes, and the Irish percussion instrument – the bodrum. People are now most familiar with the Scottish pipes, but there were Irish and northern English pipes, which usually had a less strident sound. The piper, Eugene Daly, aboard the Titanic, became famous for playing Erin’s Lament after Queenstown. For a description of the difference between bagpipes, go here. And, of course, there were other nationalities aboard, who might have brought their musical instruments with them. Lebanese / Syrian emigrants to the USA took a number of strange-sounding instruments with them, including the oud, kanun, rabab, ney, riq and tableh.

All over the Titanic, music was probably genteely tinkling, boisterously evoking memories of home, or just being mustered to entertain - and educate, of course - the children for a while. Contemporary versions of The Wheels on the Bus included The Alphabet Song, Five Currant Buns, One Two Buckle My Shoe, and This Old Man.

Although they shared language and cultural aspects, there were differences in music between the Americans and the British, the latter not directly benefiting from the hugely innovative and seductive Afro-American contribution, which would become increasingly pervasive during the 1920s and the Depression. On the British side of the Atlantic, there were popular music hall songs of surprising durability which would most likely have been heard on the Titanic, and even if we cannot recall all the words, most of us know the tunes to this day. There were no British “charts” of best-sellers before about 1940, so we have to rely on anecdotal evidence about what sort of songs were sung round the pianos on the Titanic, or hummed in the shower or bath. Most music hall hits have a predominantly 3rd class feel about them (or 1st class young men), and it is very hard to imagine J. Bruce Ismay belting out the silly, but popular, Daddy Wouldn’t Buy Me a Bow-Wow as he performed his morning ablutions , although it seems feasible that he might have managed a bit of much-loved Gilbert & Sullivan, perhaps The Captain of the Pinafore in a sturdy baritone, as he stropped his razor.

Round the joanna in 3rd class, however, it is easy to imagine the Brits and Irish gathering after “tea” to while away the hours until lights out, by singing enduring favourites such as The Boy I Love is up in the Gallery (1885). Here, 1960s songstress Helen Shapiro gives us a lyrical interpretation which is rather unlikely to have been quite how the provocative Marie Lloyd sang it (Miss Piggy’s version is also available on YouTube). Ta-ra-ra-boom-de-ay (1891), and Down at the Old Bull & Bush (1907) were also great sing-song favourites, as were Oh Mr. Porter (1893) and Burlington Bertie from Bow (1900) – the latter usually sung by women dressed as men. These were not sophisticated torch songs about love and life designed to pluck at the heartstrings of listeners; they were music hall numbers with robust simple tunes to encourage the audiences to join in. And the singers needed to have powerful lungs and a compelling stage presence, there being no microphones to help them, and audiences being much inclined to vent their feelings if disappointed.

Another aspect of some of these songs is the modern interpretation that the lyrics did not always quite mean what they seemed to. Put bluntly, some of them are reputed to have been basically very rude indeed for the times, and that the audience - at least most of the men, if not all of the women - were fully aware of this. Music halls always had a bawdy reputation anyway, attracting the opprobrium of the middle-class, devout, and respectable. At the Empire in London, a partition was erected to shield the audience from the activities of women soliciting, as they were wont to do – well, it was warm and dry, and frequented by groups of well-off young men. A young Winston Churchill helped to tear it down on the commendable grounds that it was silly, and just broadcast the situation.

An interpreter of such songs, particularly those with allegedly gay content, is the writer Howard Bradshaw: Another number ... is Daddy Wouldn't Buy Me a Bow-Wow. Surely Joseph Tabrar's ‘pretty little song for pretty little children’ doesn't hide steamy gay passions? “Cassell's Dictionary of Slang defines 'bow-wow' as 'penis,' so I always knew there was something sexual about it," says Bradshaw. “Then I read in Alison Hennigan's Lesbian Pillow Book that it was performed in the dyke cabarets of Paris at the turn of the century with the meaning, 'I'm fond of pussy, but I'd also like to try a bow-wow’. That's enough to get it in the show!"

Go here, for more similar revelations, which you may or may not believe, including a gay interpretation of Any Old Iron. I myself feel that these post-modern deconstructionists of popular Victorian songs sometimes reach rather wildly for support for their theories, and it is more than possible that innocent lyrics were later hijacked for their imagery. But then I wonder again about the innocent Victorian children’s counting song This Old Man. Even as a child, I did wonder exactly what the game of knick-knack-paddywhack involved since the old man in question seemed to play it on my thumb, my shoe, my knee, my spine and - worryingly - my door. For a rather sinister interpretation of this, (unintentionally, we hope), which alarmed even the YouTube audience, go here.

Some American songs were also famously ambiguous. Here are two British comedians (Peter Cooke and Dudley Moore in 1966) deconstructing an imaginary, but quite convincing, Afro-American song - Mama’s Got a Brand New Bag - played and sung by “Bo Dudley”.

The wonderful Bessie Smith was also accused of prostituting her great voice for money by singing such songs in the Depression, when she was almost destitute. “Sadly, nobody has ever accused me of that,” sighed the British and rather dissolute jazz-singer, George Melly, before launching into frankly-explicit renditions when he reprised her torch songs in London pubs in the 1970s, in homage to her memory. As a young woman, I was there. It wasn’t always comfortable, as Melly had a roving eye, which once landed on me, much to my consternation. But it did teach me that popular songs often conceal a great deal of sorrow, and that feelings and predilections often had to be well-hidden. If you can stand any more of this sort of thing, then go here to listen to Bessie singing one of these songs, and figure it out for yourself. This was in the 1930s, so it seems long after the Titanic, but in fact the genesis of ambiguous songs progresses from the 19th century well into the 20th century.

So it is very likely that people were chorusing ambiguous songs in 3rd class on the Titanic, without necessarily knowing what they were singing about, and we can be sure that non-English-speaking passengers would have been quite bewildered. But they might have instinctively recognised and understood the camaraderie, and smiled their way through it, even if uncomprehending.

But it is not certain that 3rd class would have just been singing the vaudeville songs, bawdy or otherwise, of the day. An appreciation of light opera, and sometimes the more lyrical of heavier opera arias, and show tunes, was more widespread than it might be today. And 3rd class on the Titanic attracted a wider socio-economic spread of customers due to its facilities, and the fact that even highly-skilled and not-impoverished emigrants might find it hard to pay for a large family in 2nd class. Theatre, and musicals in particular, had an awesomely prodigious output in those days, as can be seen from the BroadwayWorld database, from 1911 only.

London theatres were equally busy, pumping out music into the general public awareness.

The Irish, of course, famously musical and poetic, comprised a large contingent of emigrants in 1912. James Cameron’s 1997 Titanic depicts a “real party” in 3rd class, with debutante Rose displaying an unlikely ability to clog-dance, albeit without her vitally-important shoes. It is equally unlikely that quite so much drinking was going on either in reality, as poverty would have circumscribed boozing. But the Irish have a tradition of evocative and nostalgic songs reflecting their diaspora under British rule and famine. One of the saddest songs can be heard, sung by Danny Doyle, here. And to see how Rose really should have danced, accompanied by the great Celtic (actually Dutch) musicians, Rapalje, of a frankly alarming Braveheart aspect, go here. And, note, the girl has polished her shoes, unlike the boy.

There was probably less do-it-yourself musical camaraderie among the toffs in 1st class, and the upwardly-mobile passengers in 2nd class, however. Except among the young, maybe. Music has always bound the young together as a generation, rather than as the dutiful offspring of their parents’ traditions, hopes, and ambitions. Not everybody rebels, but many do, if only for a decade or so before responsibility crushes them and sends them scurrying for the certainty of their parents’ values. The 1953 film Titanic (Dir. Jean Negulesco, starring Clifton Webb) has a scene where Captain Smith encounters the young shortly before disaster strikes, exuberantly gathered round the piano in 1st Class, singing popular songs. He listens, and smiles. He’s growing old, but he recognises their vitality and potential, and lights his pipe to enjoy their happiness (3.28 minutes).

Then there was American music, which was different to European, or even British, music. But it travelled very well. “Perfessor” Bill Edwards, a man of extraordinary musical generosity and a great pianist, has created midi-files which give us a great flavour of the popular songs and tunes of the time. You can explore his website for songs and ragtime of the era, including Come, Josephine in my Flying Machine.

Of course, the probability of there being musically-talented Americans travelling in third class on west-bound luxury liners is less likely in 1912 than in later years, despite Cameron’s Jack. But young ones could well have been in 2nd or 1st Class travelling back home, and they might have shared their music, and the young Europeans on board would have eagerly listened. One of the most famous, and enduring, songs of the time is Oh! You Beautiful Doll (Brown & Ayers, 1911). Here is a one-hundred year old recording of it by Billy Murray and The American Quartet, which gives an insight of how it might have been sung around a piano on the Titanic. And a young Sophie Tucker was giving her all too, with Some of These Days (1911).

But it is now time to return to Wallace Hartley and the Titanic band after all this musical speculation. A good article about both Hartley and the band, Titanic’s Valiant Musicians, by Jack Kopstein, is available here, which makes the point that the night of the sinking might have been the first time the eight of them played together, as the requirements for music on board meant that they usually performed as trios or quartets. They were not actually employed by the White Star Line, but contracted by an agent, and travelled as 2nd class passengers, officially. It has always been alleged that Hartley’s violin was found strapped to his body after the sinking, though its whereabouts then vanished. In January of this year, an unknown person (not a relative) announced - somewhat opportunely, some might think - that he possessed this violin, and was putting it up for sale, when it might be expected to become the most valuable wreck artefact ever. Tests, it is announced, are underway to establish if it is Hartley’s violin. My guess is that it isn’t.

The music that the band played needed to be light, elegant, relatively unobtrusive, and preferably well-known. It was, after all, basically background music to metropolitan chatter – as Hartley was made to comment in Cameron’s 1997 Titanic, “They don’t listen to us at dinner either ..” Music has other uses, of course, as was demonstrated on the night of the sinking. It is well-known not only to “soothe the savage breast” (Congreve), but to comfort the timid mind (me – when flying). Anyone boarding a modern aircraft knows that music is tinkling in the background as you stow your hand-luggage, buckle-up, clutch the handrest, and taxi to possible doom. Although it has to be said that a trio of live musicians could probably do a better job of calming the nervous than a tape, if it were possible. This, Hartley knew. And before the final piece of music – whether it was Nearer My God to Thee or Songe d’Automne, as suggested by Harold Bride, he would have played the soothing background repertoire that the passengers had heard before. At least, the 1st class passengers had.

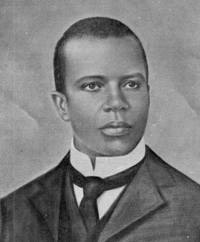

Waltzes were popular, including Strauss and Offenbach. Used in Cameron’s 1997 film, here is the Valse Septembre (Felix Godin). On this YouTube page you will also find links to many of the numbers in the White Star Line song book, elegantly performed by small orchestras or quartets. Not all the music was light opera or of middle-aged genteel aspect, as ragtime was all the rage. Here is a version of Maple Leaf Rag (1899) by Scott Joplin (1867-1917), for piano and violin, and I have to say the latter is quite redundant, and almost intrusive, as even I am perfectly capable of playing the entire melody on the piano, as Joplin intended.

To a musician, of course, early ragtime is quite classical in many ways; it only differs because it is syncopated. Here is Joplin’s Solace, a tune which even Mendelssohn might have been proud to have written, albeit in a different format, though it was not in the White Star Line songbook - not a bad pianist, but too much loud pedal. The melody still tugs at the heartstrings, though.

But was Harold Bride right, that the final music was Songe d’Automne, and not Nearer My God To Thee? We will never know. Songe d’Automne sounds very much like the sort of thing the band might have played at some stage, but it isn’t quite as fitting for the last moments. Here, it has a sort of Django Reinhardt feel, in other words – gypsy. And not quite right, even if in 1912 it was more sedate in its interpretation.

Finally, there are the post-sinking songs. We have already heard the incomparable John McCormack singing Nearer My God To Thee, but this was not the only tribute to the tragedy. There was the exhortation to Be British, based on Captain Smith’s alleged rallying-cry when all was lost. Highly unlikely, but it sold sheet music. One well-known folk song, often sung at American children’s summer camps is It Was Sad When The Great Ship Went Down. It is claimed that within months of the sinking, 125 songs had been copyrighted, but the ship still inspired music for years afterwards. Here is Leadbelly in the 1920s, an edited version, singing his Titanic song. Many of the songs blamed the Captain for drinking or sleeping, or highlighting the unfairness of the evacuation - the rich escaped whilst poor children drowned. Here is Loretta Lynn singing The Titanic, from the soundtrack of the film The Coalminer’s Daughter (1980).

This article is mostly speculation, of course, since we know comparatively little about music aboard the Titanic. But in those days, everybody made music, from the top to the bottom of society. Not to be able to play an instrument, or just harmonise in song, would have been unthinkable. They developed their musical abilities in school, church, at home, or down the pub, whether formally-taught or just playing by ear. The tone-deaf must have had a miserable time.

Afterword

This is an enormous subject, with information being both overwhelming, and elusive. Thanks also to my editors, but any errors or omissions – and there will be - are mine. This article would not have been possible had it not been for those generous people who record music and upload it freely for our enjoyment, especially “Perfessor” Bill Edwards. And, of course, the YouTube contributors.

Acknowledgements

YouTube, and the up-loaders: leylandfg, Obrasilio, Hawkmoon03111951, EncoreETC, PIGGIE58, hooplakidz, Vinylfun, JamesPriceJohnson, lorgain2, rapaljemaceal, moviegoer1002, upst8, nelly4535, ericah81, bachscholar, bonzovk, ENGColonel, markanderson8, falina7, brahmselius, classicalmusiconly, MarieCallas GR Channel, and goldjung.

Performers: John McCormack, Rapalje, Helen Shapiro, Bessie Smith, Vesta Victoria,, Stanley Kirby, Ivika-Bonzo, Sophie Tucker, Danny Doyle, Billy Murray & The American Quartet, The Encore! Educational Theater, Peter Cooke & Dudley Moore, Leadbelly, Acoustic Union String Band, Loretta Lynn, London Festival Orchestra & Alfred Scholtz, & Maria Callas.

Films: A Night To Remember (1958). Titanic (1953), Titanic (1997), Dolemite (1975), The Coalminer’s Daughter (1980).

Other website references in the text: “Perfessor” Bill Edwards, Wikipedia, Daily Mail, Titanic-Titanic, Jack Kopstein, Howard Bradshaw, The Guardian, University of Southern Carolina Sheet Music Library, BroadwayWorld, Rebekah Maxner, Felix Godwin.

Editors: Bob Godfrey, Phil Hind, and Jim Kalafus.

Comment and discuss