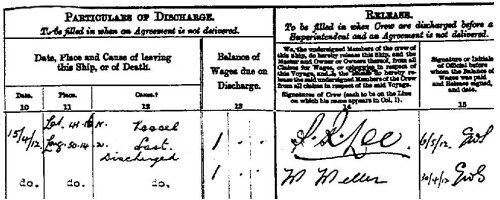

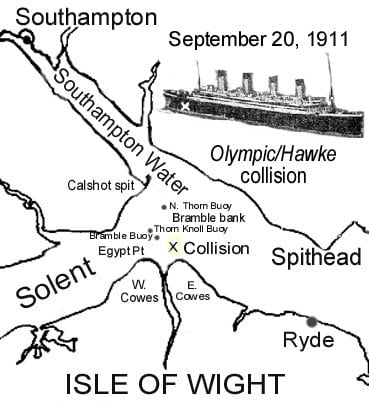

When the Olympic crept back chastened to Southampton on September 20, 1911, after being rammed in the starboard quarter by the cruiser HMS Hawke, it was not just her New York-bound passengers who felt hard done by.

Able Seaman William Clifford Weller was annoyed that he would lose out on wages for the voyage while the new vessel made "another Belfast trip" for urgent repairs. He was given only three days' pay for the abortive crossing.

But William Weller felt he was entitled to money for a month!

Perhaps Weller was one of those all-too-typical "sea lawyers," the type of garrulous militant found on every seagoing craft, the men who knew their rights and were determined that no-one was going to take the slightest liberty with their labour.

Such men commanded huge respect among their peers, just as they were the bane of the lives of their superiors.

J. G. Bisset of the Carpathia, one of the rescuers of the Titanic survivors, recalls in his book Ship Ahoy! (nautical notes for ocean travellers, 1934) the magnificent example of one sea lawyer "who could think of nothing else to growl about" and went along to the Captain to complain that there were only 41 holes in his biscuit.

"The Captain's reply need not be recorded here, but my curiosity being aroused, I went forward to the half-deck and counted the holes [in a biscuit] and found there were 42. The old sea lawyer had evidently struck a dud."

HMS Hawke before and after the collision with the Olympic.

Weller, who had served from his teenage days in that seed-bed of grousing that is the Royal Navy, thought he knew his law. When the Hawke struck the Olympic, Weller believed he had struck gold.

Later to survive the wreck of the RMS Titanic, William Weller enlisted the alliance of one Thomas Fraser, a fireman, in a plan. Together they tried to get the White Star Line to observe the letter of the law:

| HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE This claim, referred to the Admiralty Court by the Justices of the Borough and County of the Town of Southampton, arose out of the collision between the White Star Liner Olympic and HMS Hawke on September 20th last [1911]. Diagram of the Olympic - Hawke collision The plaintiffs, Thomas D. Fraser and William Weller, summoned the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company, as owners of the Olympic at a Petty Sessional Court on September 29th last for £11 damages under Section 162 of the merchant Shipping Act, 1894. The plaintiffs had signed Articles on September 16th, as a fireman and seaman respectively on the Olympic, for a voyage from Southampton to New York (via Cherbourg and Queenstown) "and/or if required to any port or ports within the North Atlantic and South Atlantic oceans, trading as may be required until the ship returns to her final port of discharge within the United Kingdom for any period not exceeding twelve months" at wages of £6 and £5 per month respectively. The plaintiffs joined the ship on the 20th, and on the same day, in consequence of the collision with HMS Hawke, the Olympic returned to Southampton in a damaged condition; and on the 22nd the defendants tendered to the plaintiffs three days' wages. The plaintiffs claimed one month's wages, and on the defendants' refusal to pay, proceedings were brought in the Petty Sessional Court as a test case - a sum of over £4,000 being involved. THE ISSUES The plaintiffs based their claim on Section 162 of the Merchant Shipping Act, 1894, which provides that: "If a seaman, having signed an agreement, is discharged other than in accordance with the terms thereof before the commencement of the voyage, or before one month's wages are earned, without fault on his part justifying that discharge, and without his consent, he shall be entitled to receive from the Master or owner, in addition to any wages he may have earned, due compensation for the damage caused to him by the discharge, not exceeding one month's wages, and may acquire that compensation as if it were wages duly earned." The defendants relied on Section 158 of the Act, which provides that "when the service of a seaman terminates before the date contemplated in the agreement, by reason of the wreck or loss of the ship... he shall be entitled to wages up to the time of such termination, but not for any longer." The point, therefore, centred round the question whether, under the circumstances, the Olympic was a "wreck," and the Justices being evenly divided on the point, the claim was referred to the Admiralty Court under the power contained in subsection 3 of section 165 of the Merchant Shipping Act. By agreement, the shorthand note of the evidence taken before the Justices was used, and no fresh evidence was called. Mr Emanuel, appeared for the plaintiffs, and Mr Laing K.C. and Mr W. Norman Raeburn for the defendants. ARGUMENT FOR THE PLAINTIFFS Mr Emanuel, for the plaintiffs, contended that the only grounds on which the defendants could escape liability to pay a month's wages was that the Olympic was a "wrecked ship." This did not mean a ship unable to proceed to sea - she could be unfit to go to sea without being a wreck. He referred to section 331, subsection 1, of the Merchant Shipping Act. What happened to the Olympic did not make her a wreck, although it rendered her unfit to proceed. Mr Justice Deane - "What is the definition and derivation of the word 'Wreck'?" Mr Emanuel - "It is very difficult to define. Stroud's Judicial Dictionary defines wreck as 'where a ship is perished on the sea, and no man escapeth alive out of the same.'" Continuing, counsel cited the case of Legge v. Boyd [14 L.J.C., p. 138] which held that a vessel which had been in collision was not wrecked merely by being damaged and striking the shore, although the facts were that she was so much damaged that the owners sold her for one-third of her cost. In this case the damage in proportion to the size and value of the ship was far less, although no doubt costly. He also referred to the Elizabeth [2 Dodson, 403]. Mr Justice Deane - "What is the distinction between a lost ship and a wreck under section 138 of the Act?" Mr Emanuel - "A wreck is a vessel which has touched the ground." In Constable's case [77 English Reports; 219] it is stated that nothing shall be said to be wraccum maris, but such goods only which are cast or left on the land by the sea. In the King v. The Forty-Nine Casks of Brandy [3 Hagg, AD 257], a similar definition was adopted. The King v. Two Casks of Tallow, in the same report at p. 296, was also referred to. He submitted for these reasons that the Olympic was not a wreck, and that the plaintiffs were entitled to succeed. ARGUMENT FOR THE DEFENDANTS Mr Laing, for the defendants, said that the two plaintiffs, when asked in the court below if they would have gone on in the Olympic as she was, said "decidedly not." A round voyage would occupy eighteen days and no more. It was also to be noticed that her passenger certificate was taken away after the collision, and she did not get it back until after the repairs were executed, and she did not in fact sail until November 29th. He submitted the case did not fall within Section 162, and even if it did, it was taken out of it by Section 158. He contended that wraccum maris and flotsam and jetsam cases which had been cited had no bearing on the point. Wraccum maris referred to common law wreck in connection with the ownership of things washed up by the sea. Section 158 of the Act shortly came to this, that if either the man or the ship was unfit to proceed to sea, the man could not recover wages after that time. In the Woodhorn case [92 Law Times Journal,113], it was held that a vessel which had been scuttled and then raised after abandonment to the underwriters was a wreck. He also referred to the Austin Friars Steamship Company v. Strack [51The Times LR 556] and Sivewright v. Allan [22 The Times LR 482], cases of loss by capture at sea arising out of the Russo-Japanese War, as to the meaning of the word "loss" in Section 158. A wreck under Section 158 did not mean a permanently stranded vessel between high and low water mark. If that were so, a vessel the size of the Olympic could never be a wreck!

The Century Dictionary defined a wreck as "a partial or total destruction of a vessel at sea... by any accident or navigation, or by the force of the elements." Section 162, under which the plaintiffs based their claim, in effect gave damages for wrongful dismissal. It did not alter the common law of the realm that damages depended on the dismissal being wrongful.What wrong had the owners of the Olympic done? The contract of service depended on the continued existence of the ship in a fit condition to be navigated, and through no fault of her own she was not in that condition. In Tindal v. Davison [66 Law Times R. 373], it was held that the voyage having lasted only 21 days, the seaman was not entitled to a month's wages as his discharge was not improper. Taylor v. Caldwell [3 B & S, 826] was also referred to. Finally he submitted that it had not been proved that the plaintiffs were entitled to the full month's wages; and the question of damages, if any, was entirely one for His Lordship, as the voyage in fact would only have lasted 18 days. Mr Raeburn, who followed, cited Nicholl v. Ashton, Eldridge & Co. (17 The Times L.R. 467]. The contract had been rendered impossible, and both sides were released from the further performance of it. The arguments were not concluded when the court adjourned. (Daily Chronicle, Wednesday March 6, 1912, p.22) | |

| Mr Emanuel this morning replied to the arguments put forward by the defendants. Dealing with the case of Nicholl and Knight v. Ashton, Eldridge & Co. [17 The Times LR 467] he said the case mainly decided that the stranded vessel was not in a position to carry cargo. It had nothing to do with seamen. Further, there had been no performance of the contract at all. In the present case the crew had joined the Olympic and started in her, and there had been part performance. The case of the Austin Friars Steamship Company v. Strack [21 The Times LR 556], and Siveright v. Allan [22 The Times LR 482] were merely decisions as to whether capture by a belligerent was a "loss" within Section 158 - they had no bearing on the meaning of "wreck." A few days ago one read that the Olympic had broken a blade of her propeller. Supposing that instead of a small breakage she had lost her propeller, she would then have been a damaged vessel and unable to proceed to sea, but could it be said that she was a wreck? He contended not. With regard to the amount of damages the plaintiffs were entitled to recover, he submitted that the uncontradicted evidence, which had not been cross-examined to, was that their damages were the amount claimed. Mr Justice Deane - "The withdrawal of the Olympic's passenger certificate by the Board of Trade may be some evidence that she was a wreck - the licence would only be withdrawn because the vessel was not seaworthy." Mr Emanuel said he thought the men were discharged before the certificate was withdrawn. At any rate, they were discharged independently of that. He did not say the owners were not entitled to discharge the men, but they had to do it under the conditions of the Act - viz, by paying a month's wages under Section 162. THE OLYMPIC'S CERTIFICATE Mr Justice Deane said it might be important, and he would like to see the certificate and to have the date of its withdrawal. Mr Laing accordingly called Mr Phillip Currey, Manager of the Southampton branch of the White Star Line. He said that on the afternoon of September 21st, he received a verbal message that the Board of Trade would require the Olympic's certificate to be surrendered. He replied that if the Board of Trade were going to demand its surrender, he would be obliged if they would put the request in writing, and they subsequently did so. He could not remember the exact date, but the letter had been handed in to the Justices. The certificate was only got back a day or two before the Olympic sailed on November 29th. Mr Justice Deane said the letter was not among the papers which had been sent up by the Justices. The date was important, and he would adjourn the case for the registrar to write for the document. Failing its production, if the authorities at Southampton could agree the date that would be sufficient. Judgment was reserved. (Daily Chronicle, March 7, 1912, p.22) |

WHILE all this was going on, William Weller was serving on the Oceanic, plying the Western Ocean with the very same employers with whom he was embroiled in judicial dispute. Returning to Britain in March, he found his case hanging in the balance, but still there was no shortage of work with the White Star Line. Even if it were not a case of all the proprieties of the sub judice rule being observed, White Star still had to muster crews.

But then the coal strike intervened and many sailings were cancelled. Nonetheless, William Weller was still in favour. He was one of a party of crew formed up at the West Station at Southampton at 2.30pm on March 26, 1912, and indentured on the Articles of the line's newest ship. The crew travelled by train to Liverpool, where they boarded a steam packet across the Irish Sea to Belfast.

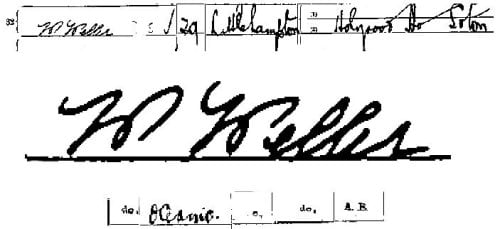

Herbert James Haddock appears as the Captain on the first crew agreement for the RMS Titanic [PRONI trans 2A/45/381A), and William Weller's signature is just three lines below. The same 29-year-old from Littlehampton, Dorset, who appears on the agreement for the Olympic's mishap voyage, is here signing on as a quartermaster, at the same rate of pay as an able seaman.

A crew of just 280 were aboard when the cold streaks of early morning saw the Titanic glide out of Belfast Lough for her deep-water baptism.

It was April 2, 1912, and she was running past the Copeland Islands on her sea trials when it might have occurred to William Weller that his case was being decided in London that day. But he had no chance of learning how it turned out - after a full day of turns and tests, the Titanic sailed at 8pm for Southampton.

Weller's signature and details for the Titanic's Atlantic voyage are the same as for the delivery trip and Olympic voyage of September 20, 1911.

| THE JUDGMENT Mr Justice Bargrave Deane said that in this case two members of the crew of the Olympic, of the White Star Line, brought a claim before the magistrates at Southampton claiming wages as a fireman and a seaman respectively in the Olympic for a voyage from Southampton to New York (via Cherbourg and Queenstown), trading as may be required until the ship return to her final port of discharge within the United Kingdom for any period not exceeding twelve months. The plaintiffs joined the Olympic on September 20 last year, and the vessel proceeded from Southampton, but as was well known the vessel came into collision with His Majesty's Ship Hawke, and received such heavy damage that she had to go back to Southampton, where she discharged her cargo and passengers, and after being patched up, proceeded to Belfast, where alone she could be dry-docked, for her repairs, and she did not sail again until November 29th. The whole question turned on the meaning of the words in Section 158 "wreck or loss of the vessel." There was no definition in any of the Acts as to what a "wreck" was, and it was agreed that His Lordship had to base his decision on the meaning of that word. Was the Olympic a wreck within the meaning of that section? A good many cases had been cited to him on the one side and on the other, but counsel for the claimants had been unable to find any case in which it had been held that a vessel was or was not a wreck, and he had cited cases in relation to goods - Legge v. Boyd, the King v. The Forty-Nine Casks of Brandy, the King v. The Two Casks of Tallow. These were cases as to whether goods were "wraccum," a very odd word, which His Lordship believed came from the old Anglo-Saxon. They were disputes as to whether goods washed ashore out of vessels belonged to the owner of the foreshore or to some other person, and depended on whether they were "wraccum maris" or not. They did not touch the meaning of the wreck in Section 158. In His Lordship's opinion, the Olympic was a "wreck" within the meaning of Section 158. The words were "wreck or loss," and wreck was something short of loss. If the vessel foundered, she would be a loss and not a wreck. He thought that in the Elizabeth [2 Dodson, 403], Sir William Scott used the word "semi-naufragium" and we now used the expressions "a partial wreck," "a constructive wreck," "a constructive total loss," and we recognized the qualification of losses and wrecks. The whole question was whether the vessel was sufficiently injured and damaged that she ceased to be a ship of serviceable character to her owners. His Lordship thought that the nearest approach to the present case was that of the Elizabeth. That vessel was damaged and burned, but in the end she was repaired, and the Master in the exercise of his discretion discharged the crew in a foreign port and they were sent home, and everything was done to mitigate the damage. In a claim by the crew for wages - it was long before the Merchant Shipping Act - Sir William Scott said the question was whether the Master had a right to dismiss the mariners, and that the circumstances in which the vessel was placed did vest him with the authority to do so: - "Here was a ship which had encountered what the law might call a 'semi-naufragium' - full of water so that they could not live on board. She is put in the hands of foreign carpenters for a protracted course of necessary repairs... is it clear law that the Master, acting for his owners, could not in such circumstances dismiss the mariners on any terms whatever? "If so, then he was bound to keep this crew in an unemployed state, living on shore, and keeping holiday all the winter at the expense of his owners... I know and feel the partiality which the maritime law entertains for this class of men, but it must not overrule all consideration of justice to the other classes, particularly to the merchants, their employers; for what is oppressive to the merchant cannot but be injurious to the mariner." That, to his mind [Mr Justice Deane's] properly stated what the principles were. THE OLYMPIC'S CERTIFICATE Now, the Olympic was so seriously damaged that she ceased to be a navigable ship. She went back under her own steam to Southampton, and on the 22nd the men were discharged. The men were offered wages up to that time, but they - or so far as this action was concerned, these two plaintiffs - claimed wages for a month. Was the Master of the Olympic justified in discharging them? In His Lordship's opinion he was. Both the plaintiffs agreed that it was impossible to have gone on serving in the ship - and what stronger evidence could there be of her state, and that she was, in their opinion, a wreck? Before that, on September 22nd, there was a letter from officials of the Board of Trade handed to the Manager of the White Star Line at Southampton requiring the return of the Olympic's passenger and freeboard certificate because she was not in a seaworthy condition, and the certificate was duly returned. The vessel then could not proceed as a passenger ship; she was under the embargo of the Board of Trade, and she was only patched up sufficiently to enable her to get a certificate to proceed to Belfast and no further. His Lordship held therefore that the plaintiffs were not entitled to wages beyond the date to which they had been tendered, and he gave judgment to the defendants on the claim, with costs. A stay of execution was granted. Solicitors - P. J. Nicholls for Emanuel & Emanuel; Thomas Cooper & Co for Hill, Dickinson & Co. (Daily Chronicle, Tuesday April 2, 1912, p.4) |

SO William Weller and Thomas Fraser lost out on their sea lawyer gamble. Weller would have learned the outcome when the Titanic arrived in Southampton, scene of the Olympic's shunt, on April 4, 1912. Too bad, as he might have consoled himself in a quayside tavern. But definitely worth a try.

Yet William Weller's "test case" was about to have major implications in the case of his new vessel. The very month that the Titanic sailed, the High Court had determined in a major finding the limitations of the obligations on an employer in relation to the unforeseen termination of a voyage. The White Star Line had saved £4,000 - and may have wished within a few days that it had been otherwise.

Because when the Titanic sank, the White Star Line encountered huge public opprobrium. And amid the swirling allegations and counter-claims, one inalienable fact could be seized upon as evidence of the company's gutless greed and inhuman avarice. When the vessel sank on April 15 at 2.20am, the pay of the poor crew ended as if by guillotine. The cheek of White Star!

Thus the men were indeed cast up as flotsam and jetsam in America, where public generosity shamed the company. Where the issue of the stopped pay was interpreted only one way, and not as a properly-found legal protection against crews who would seize anything they could. And where a far more insidious idea could take hold - that if the White Star Line had a policy of immediately stopping the pay of shipwrecked seamen, might it also suggest that marine catastrophes were never too far from the company door?

Who would want to sail with a company like that?

William Weller's Atlantic crossing on the Titanic began routinely, but there was a glimpse of future controversy. When the ship was at Southampton, lookout George Alfred Hogg locked away the binoculars he had been loaned by Second Officer David Blair in the latter's cabin. He gave the keys "to a man named Weller, as I was busy on the forecastle head."

Some glory-hole ribbing can also have been expected of Weller by his mates, but he would have had the perfect riposte in pointing out that if he had won his case then all of his detractors would have been quids-in too. You have to look after "number one," as the company cares only for itself...

And so when crisis struck, it might be little surprise to note that William Weller was first in line for a place in the very first boat.

From the evidence of lookout Archie Jewell -

97. Did you count as one of the two seamen for this boat (Lifeboat 7)? — Yes.

98. Who was the other? — Weller.

99. You say Mr. Murdoch said “women and children first,” and what was done? — Well, we put all the women in that was there, and children. Up to that time there was not many people; we could not get them up. They were rather afraid to go into the boat; they did not think there was anything wrong.

Weller returned to Britain on the Lapland. Just two days later, in a particular irony, he was signing for the £1 he was due as the balance of his wages as a result of his unusual discharge in mid-Atlantic.

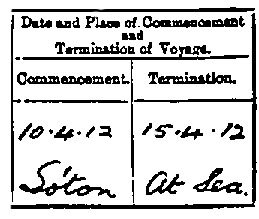

The sign-off papers for the survivors show the latitude and longitude of where the discharge - that is to say, the sinking - took place. Weller signed for the money on April 30, 1912, and his signature, with the trademark M-type Ws, appears just below the flamboyant hand of lookout Reginald Robinson Lee.

Particulars of Discharge

Crown Copyright (image clarified by the author)

If Weller had won his case earlier that month, he and the entire crew would have been entitled to far more. It is, perhaps, one of the ironies of history that White Star had won a legal battle only for that very victory to help it to lose the confidence of the public less than a fortnight later.

Weller later received £8 twelve shillings and sixpence witness expenses from the British Inquiry (nearly $44 in 1912), although it seems no-one felt the need to put the sea lawyer back into evidence. Weller's court career was over.

|

| William Weller (from CR10 identity card) |

William Weller received money and goods from the Titanic Relief Funds, visiting the American Embassy for his share of monies raised in that country. In Southampton he received 2 pints of milk per day, plus a weekly bag of coal for heating. He went on to have four sons - Stan, Fred, Ernest and John, some of whom followed him to sea. He died from pulmonary tuberculosis on May 1, 1954 at his home at 17 Beatrice Road, Southampton. He was 72.

Comment and discuss