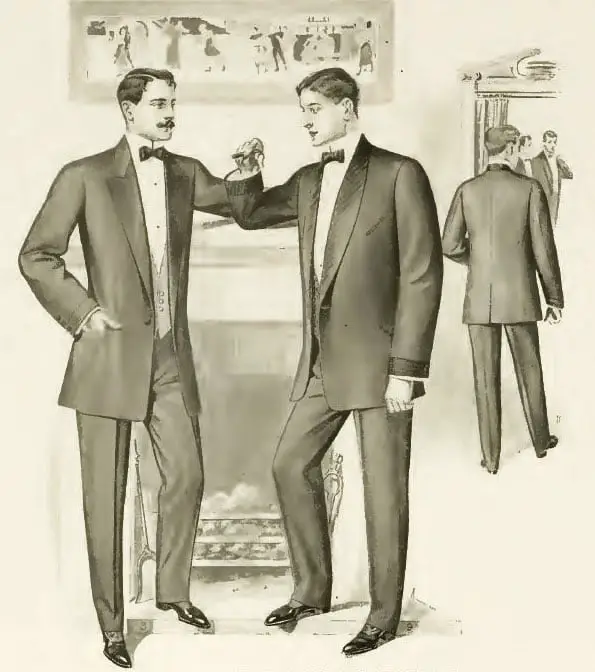

In the James Cameron-directed film Titanic (1997), the First Class Dining Room scenes set aboard ship are memorable for their lavish costumes. The actors are resplendent in dress for a high evening occasion — men in white tie and tails and women in ball gowns — clothes suited to a banquet or opera premiere, not a dinner at sea. While a few of the less fanciful evening dresses might have been worn on the real Titanic, none of the men’s formal suits would have been worn. To those who study the customs and styles of the Edwardian era, these scenes in the film are both beautiful and ridiculous.

(Twentieth Century Fox)

It’s true that the night of Sunday, April 14, 1912 was a particularly festive one, probably the first and only such event aboard Titanic, then five days out on its maiden voyage. Passengers would recall as much in their accounts in letters to family and friends as well as in interviews with newspaper or magazine reporters.

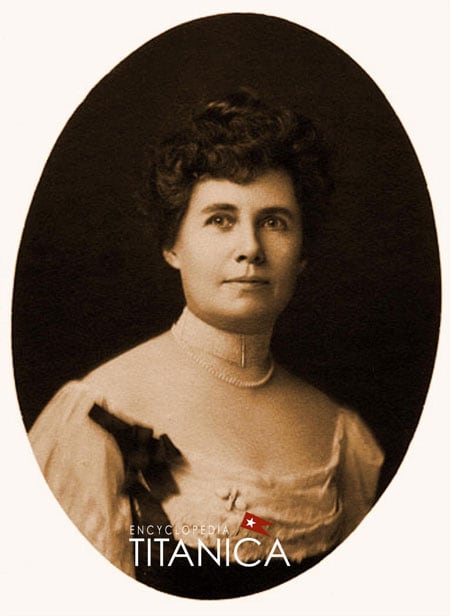

In this analysis, we will see that, while their advice wasn’t always followed, two imminent specialists in the manners and dress of this period — Mrs. Post and Mrs. Holt, both named Emily — spoke to what was appropriate for men and women to wear at sea at the dinner hour. So did another voice of authority, fashion consultant Anne Rittenhouse.

Glamorous clothes at sea?

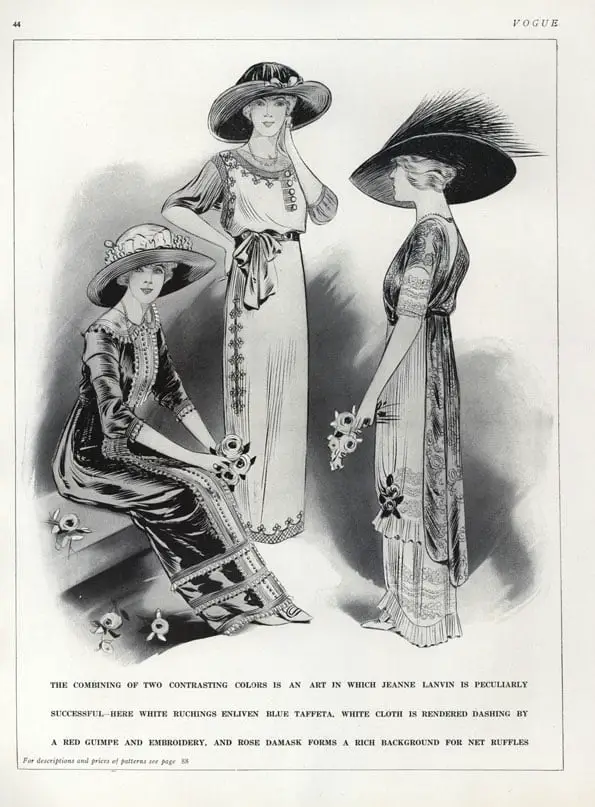

Ocean-going entertainments in the Edwardian period were not generally occasions for which one’s most opulent attire was worn, at least not by most First Class passengers of means and social experience. There were gradations of formality in dress in those days and shipboard dinners were not considered formal but rather semi-formal affairs. By the last years before World War I (1913 and 1914), the enormous popularity of ragtime music and dancing had begun to alter people’s manner of dress with more leeway being observed in what was thought appropriate for party attire.1 But as of early 1912, the fad of “jazz dancing” and the new-fangled Tango was just starting and as yet no English or American ships were regularly hosting dances in their First Class public rooms.2 Wardrobe selection was still relatively subdued for evenings at sea; attractive and stylish, of course, but not glamorously extravagant.

(The Vogue Archive)

“On the de luxe steamers,” wrote socialite and etiquette expert Emily Post (Mrs. Price Post), “nearly every one dresses for dinner; some actually in ball dresses, which is in the worst possible taste, and, like all overdressing in public places, indicates that they have no other place to show their finery. People of position never put on formal evening dress on a steamer, not even in the à la carte restaurant, which is a feature of the de luxe steamer of size.”3

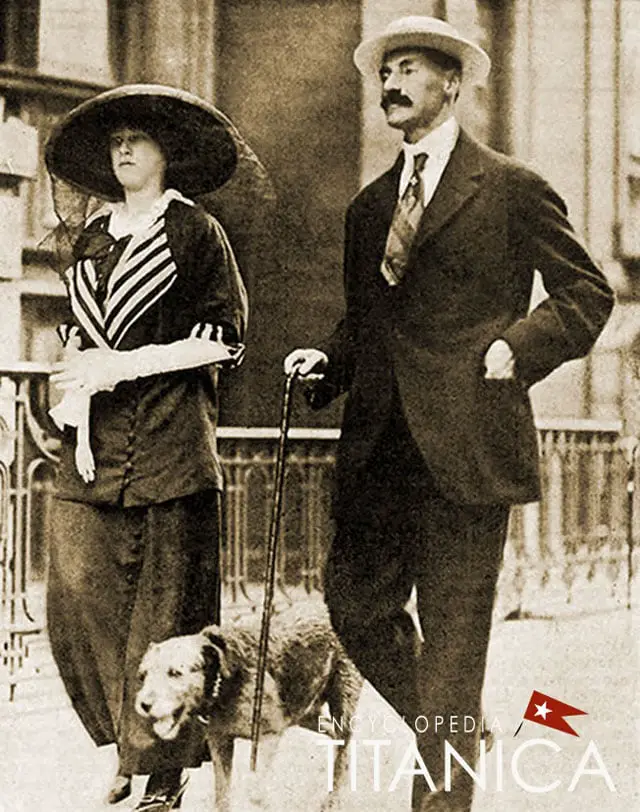

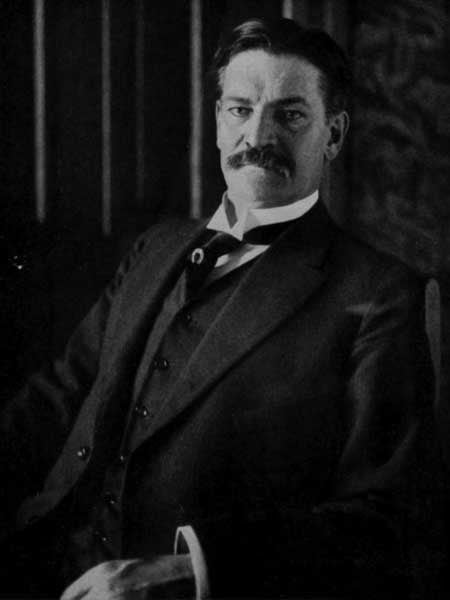

Titanic passengers as well-heeled as multimillionaire Col. John Jacob Astor IV, returning from a European honeymoon with his bride, the former Madeleine Force, were well-accustomed to appearing at magnificent events on land. Indeed, many of Titanic’s First Class ladies and gentlemen were regular guests in grand private residences and hotels where they met other highly distinguished persons, including royalty and politicians. To these passengers, dressing at sea was not regarded as an opportunity to display their wealth and taste; they had no need to show off their most brilliant attire among people with whom they would not ordinarily socialize.

(Randy Bryan Bigham)

Eveningwear on Titanic

So what did First Class passengers on Titanic actually wear for dinner, particularly on the historic night of April 14th?

Fortunately, there’s no shortage of first-hand memories on the part of survivors of the disaster that happened only a few hours after the evening meal that day.

“On these occasions, full dress was en regle,” wrote survivor Colonel Archibald Gracie in his book The Truth About the Titanic. He referred to men’s expected appearance in dinner jackets, often called tuxedos. But he added that the presence of ladies was “a subject both of observation and admiration” because “there were so many beautiful women – then especially in evidence – aboard ship.” Fellow survivor William Sloper, a Connecticut stockbroker, decided against the tuxedo his steward had laid out for him, choosing instead (because of the cold)

a brand new suit of heavy woolen material which had just been finished for me before sailing by a London tailor.4

Another American survivor, art critic and interior design guru Helen Churchill Candee, remembered supper in the Dining Room that night as impressive. She later wrote in Collier’s magazine that

the scene might have been in London or New York, with the men in evening jackets, the women shining in pale satins and clinging gauze.5

But these dresses were not ball gowns. They were dinner frocks — lovely, even stately in style — but the elaborate headdresses and flashing jewels that might have accessorized such gowns at an exclusive dance in Paris or a country club in New York were eliminated.

(Dover Publications)

(Washington Post)

As Mrs. Post explained:

In the dining saloon they wear afternoon house dresses — without hats — for dinner. In the restaurant they wear semi-dinner dresses. Some smart men on the ordinary steamers put on a dark sack suit for dinner after wearing country clothes all day, but in the de luxe restaurant they wear Tuxedo coats. No gentleman wears a tail-coat on shipboard under any circumstances whatsoever.6

From Post’s words, typical of all contemporary etiquette buffs, a distinction was made between ordinary afternoon attire in a ship’s Dining Room and what was worn at night in a ship’s private restaurant. It was more relaxed in the Dining Room with simple afternoon dresses for women or day suits for men being favored; ladies also sometimes donned a decorative blouse and skirt. As fellow leading etiquette expert Emily Holt advised, a “gay silk blouse, a pretty foulard gown or a lace waist with a silk skirt” was in good taste.7

Hats at dinner were not generally worn on British and American ships or by women of those nationalities on other countries’ ships. But increasingly, by 1912, the influence of French fashion was being felt. European ladies, especially fashionable French or German women (or those who emulated them), were beginning to wear hats with their afternoon clothes for dinner.8

This was especially so in privately-run eateries like Titanic’s à la carte restaurant. Here, ladies tended to wear slightly more formal dinner gowns with a lower neckline. Extremely decolleté dresses that were also sleeveless were generally not thought to be in good taste. Dinner gowns, a kind of midway point between regular afternoon and formal eveningwear, could be worn with or without a hat, although American advisers on manners still disapproved of hats at dinner. For instance, Emily Holt said a lady “at dinner wears no hat; neither should a woman appear in a decolleté gown.” The mode of attire for men was always dinner jackets in the restaurant, not coats with tails as a formal dinner on land might require. Mrs. Holt stressed that “short dinner jackets with their white linen or black silk neckties” were advisable.9

Anne Rittenhouse, fashion editor of the New York Times and a Vogue magazine contributor, recorded that popular shipboard afternoon wear for dinner in the years just before World War I often involved women in “black satin frocks and coat suits with blouses of fine white batiste.”10 She made a point to observe that men “wore dinner jackets with grey silk vests instead of the formal swallow tail” for dinner in the liner’s restaurant.11 Some women in the restaurant, Rittenhouse said, “adopted the French fashion of a semi-decolleté dinner gown with a smart hat, others kept to the English and American fashion of an uncovered head to match an uncovered neck.” As to jewelry at dinner, modesty prevailed. Emily Holt made this clear: “For steamship dinners, a bit of decorative jewelry can be worn but any display of jewels is at once vulgar and dangerous.”12

Extremely formal party wear for men or women was never worn by anyone other than unsophisticated travelers. Undoubtedly, there were some on Titanic who overdressed but such a tendency was discouraged in examples set by their table companions of finer taste.

Last Dinner on Titanic

Mahala Douglas, wife of businessman Walter D. Douglas, left a charming account of the atmosphere in Titanic’s B Deck restaurant on April 14th.

We dined the last night in the Ritz restaurant. It was the last word in luxury. The tables were gay with pink roses and white daisies, the women in their beautiful shimmering gowns of satin and silk, the men immaculate and well-groomed, the stringed orchestra playing music from Puccini and Tchaikovsky. The food was superb – caviar, lobster, quail from Egypt, plover’s eggs, hot house grapes and fresh peaches. The night was cold and clear, the sea like glass.13

Rivaling Mrs. Douglas’ memories of that evening in the restaurant were the recollections of novelist May Futrelle, wife of Jacques Futrelle, himself a famous author of detective stories. She praised “the gaiety of the evening,” It was, she said,

a brilliant scene. Women beautifully gowned, laughing and talking, the odor of flowers; ridiculous to think of danger.14

Elsewhere, she expounded, also recalling a

brilliant crowd. Jewels flashed from the gowns of the women. How fondly they wore their latest Parisian gowns. It was the first time that most of them had the opportunity to display their newly-acquired finery. The soft, sweet odors of rare flowers pervaded the atmosphere. I remember at our table was a great bunch of American Beauty roses. The orchestra played popular music. It was a buoyant, oh so jolly crowd… a rare gathering of beautiful women and splendid men. There was that atmosphere of fellowship and sociability which makes the Sabbath dinner on board ship a delightful occasion.15

Still later, May Futrelle recounted:

The dinner was the most beautiful I ever saw. We remarked how we might have been in a hotel ashore for all the motion we felt. You had to look out of the portholes to realize that we were at sea. Once we turned and drank toasts to the next table. Not a person at that table was alive the next morning.16

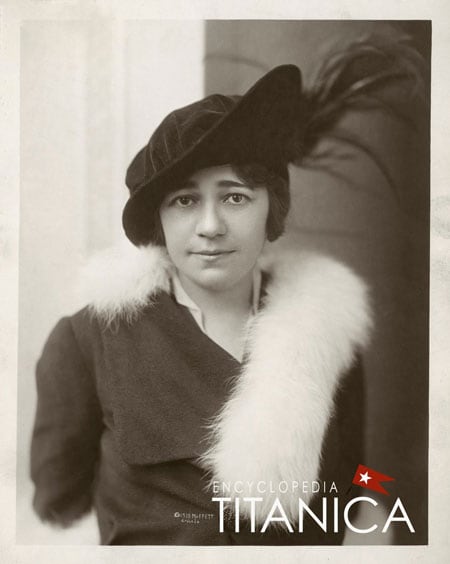

Futrelle’s reminiscences of the French restaurant indicate the toilette of some of the ladies in attendance was more extravagant than the norm. One of those whose gown was perhaps a bit overstated was her own table companion, René Harris, wife of Broadway producer Henry B. Harris, also present that night.

(Wisconsin Historical Society)

Mrs. Harris’ dress was sleeveless, not thought respectable for evening on a ship, however stylish it may have been ashore. But she had a good excuse to flout the unwritten rule. René had fallen down the aft staircase near her cabin earlier that evening and broken her right arm. Having refused pain medication prescribed by the ship’s doctor, she was still alert and insisted on dressing for dinner. But René could not lift her arm (set in a sling) through a dress sleeve so she settled for one of her sleeveless frocks.17 We don’t know what René Harris’ dress looked like apart from its being sleeveless. But we do know what other women wore that night.

Both silent screen star Dorothy Gibson, 22, and fashion journalist Edith Rosenbaum, 32, wore white. Dorothy’s evening gown was white silk with a slight train and Edith’s evening dress was white satin. Dorothy chose her gown, worn to the First Class Dining Room, because there was a “great deal of merriment on board.”18 Edith, also eating supper in the Dining Room on D Deck, wore her white dress for what she called a “gala dinner.”19 Vogue magazine approved of young ladies wearing white gowns for ocean-born suppers, once giving an example of a great beauty making an extraordinary entrance into a ship’s dining hall in white.20

Eleanor Cassebeer, another young First Class passenger, also chose a white dress on April 14th but a more conservative one of muslin, a plain, sheer fabric used for afternoon as well as evening gowns.21 Muslin was a decision of which Mrs. Post might have approved.

(Randy Bryan Bigham)

We don’t know what Charlotte Drake Martinez Cardeza wore that night but she certainly had her pick of fine clothes. She was traveling with 14 trunks that included many designer dresses from Paris, including a collection of Redfern, Worth and Lucile gowns.22 Marian Thayer was one of the guests at a small dinner party in the a la carte restaurant so she likely was prettily turned out in one of her own new Paris dresses, topped perhaps by one of her Worth evening wraps.23

Noëlle, Countess of Rothes wore a dinner gown to the Dining Room and with it a necklace of recently restrung 300-year-old family heirloom pearls. Many of Lady Rothes’ clothes were from the firms of Loyse and Francis, conservative London dressmakers. Madeleine Astor, wife of the richest man aboard, chose “an attractive light dress,” either an afternoon or dinner frock. The Chicago Examiner and other papers affiliated with the Hearst Syndicate described what she wore as

an evening gown over which was a handsome cloak with a fur collar. She had no hat and her sole head protection was a filmy silk veil.24

Marjorie Newell recalled to a friend, TIS President Emeritus Shelley Dziedzic, that

she and her sister used to wait at the bottom of the grand staircase to see all the ladies descend in their finery.

Newell added that “she could remember the rustle of the trains on the gowns as they swept down the staircase.” She and her sister, Madeleine Newell, traveling with their father, even dined one night aboard Titanic with the Astors. 25

(The Vogue Archive)

Similarly, Helen Candee recalled the elegant lady passengers arriving for supper in their “sweeping dinner gowns.” Candee may have admired the beautiful dresses worn by others on April 14th but she didn’t fully describe what she wore herself. All that’s known is that it was an evening dress accessorized with a shoulder scarf. Mrs. Candee did admit that she never wore black stockings, only colored ones.26

For all the emphasis on lovely gowns, the increasing cold of that day prevented some from choosing such light evening apparel.

(Randy Bryan Bigham)

A notable instance of this was the case of Lucy, Lady Duff Gordon, otherwise known as ‘Lucile,’ one of the most celebrated fashion designers of the day. Traveling with her second husband, Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon, and her personal assistant, Mabel Francatelli, Lady Duff Gordon could have worn the most beautiful clothes if she wished. But she had no interest in it tonight. Lucile wrote in her memoir:

The wind was the coldest I ever felt, but it died down toward night. As we walked round the deck, I shivered in my warmest furs. ‘I have never felt so cold,’ I said to Cosmo… And when we all three went down to dinner in the restaurant, we kept on our thick clothes instead of dressing for dinner.27

In examining Lucile’s unfiled claim against the White Star Line for her lost luggage, she doesn’t list any dinner dresses, only evening frocks whose descriptions seem too elaborate for shipboard wear. She does mention several afternoon gowns that she may have worn on other dinner occasions while aboard — a white charmeuse dress and coat, a chocolate brown dress and coat, a black velvet gown and another in black chiffon. As for the “thick” day clothes she wore to the a la carte restaurant on the night of the accident, Lucile’s inventory itemizes several tailored blue serge dresses and suits as well as a gray suit. She also had with her a white “traveling costume” and another in tussore, a kind of silk.28

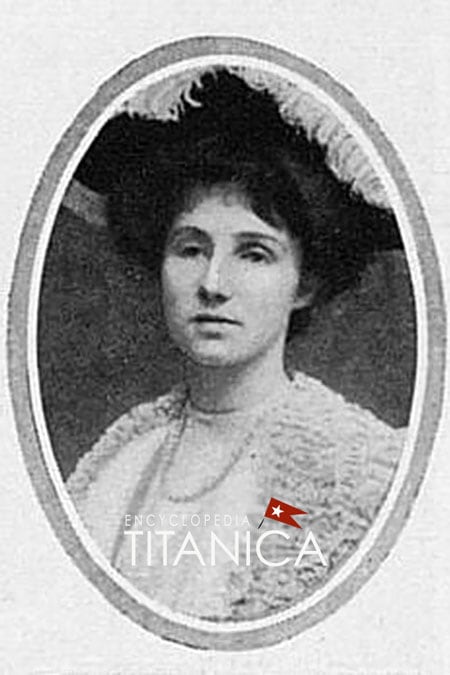

(Michael Beatty)

Denver millionairess Margaret Brown had a similar reaction to the chilly evening. Women all day had been wearing “luxurious furs,” she recalled, and the men were “in heavy overcoats buttoned closely around their necks.” Toward nightfall, the cold worsened so that many wanted to keep on their “heavy furs and warm clothing.” She added that:

Dinnertime found few inclined to shed their warm clothing for dinner dress. Even the innumerable brides who on various occasions had appeared in a different Paris creation each night could not be induced to change.29

In another news account, Margaret admitted the coldness of the evening was why she opted to wear to dinner a velvet dress, a matching jacket and sable stole which she apparently later wore to abandon ship. With her velvet dress, Margaret wore a $15,000 diamond brooch that was later stolen, she claimed.30

(Colorado Historical Society)

Antoinette Flegenheim observed the same trend of not dressing for dinner, although she attributed this to its being a Sunday which was generally an uneventful time aboard ship.

“The last night on board being a Sunday night, many of us didn’t dress for dinner, but kept on heavier clothes and retired earlier,” she wrote.31

Glamour vs. good taste after 1912

With the rise of café society just before World War I, people of all classes and cultures met on the dance floor or at the cocktail bar, streamlining social interactions and loosening strict codes of etiquette. The international dance craze which had started in about 1911-12 was one of the strongest catalysts for change in morals and dress. What was once considered ill-mannered became increasingly the “done thing” in society on land and sea — and that applied to clothes as well.

Aboard European ocean liners, “jazz dancing” men and women — many of those women in low-necked, sleeveless dresses — were a mainstay by the end of 1912, most notably on German and French ships where liberality in manners, modern customs (such as women smoking) and fashionable dress were followed more and more keenly.32 René Harris’ sleeveless dress on Titanic would not have raised an eyebrow six months to a year later.

As Anne Rittenhouse recalled of a voyage she took aboard the German liner Imperator in early 1913, more and more women were “overdressing.” They had on, to her mind, “too many jewels and their gowns were a trifle more gorgeous than is usual on shipboard.” But Miss Rittenhouse did not entirely disapprove of the change and predicted that ships like Imperator might “set a new style in dressing” at sea so that “what we once considered bad taste will hereafter be good taste.”33

For dancing, Rittenhouse noted especially that the shipboard pastime “combined all that is new and brilliant” in fashion – sequined gowns with slit skirts that had been brought into style by ballroom dancer and soon-to-be film star Irene Castle.34

Those last three years before the Great War saw many changes in dancing, manners and dress but they were fleeting. The war came and the current of frivolity was suspended until war’s end in 1918. The comparatively naïve world of society aboard Titanic and its staid approach to style seemed a long way in the past.

(The Vogue Archive)

Acknowledgements

This article first appeared in print in the summer 2023 issue of Voyage, the journal of Titanic International Society. First of all, I thank Gregg Jasper, a friend of René Harris in her later years and my coauthor in writing her biography, for his recommendation that I address how dinner party wear on shipboard differed from formal eveningwear on land. I am also grateful for his useful editorial suggestions. And I thank Mike Poirier and Shelley Dziedzic for sharing with me their memories of Marjorie Newell Robb, the last living First Class Titanic survivor.

Notes

- Collier, Simon, ed., Tango: The Dance, the Song, the Story. London: Thames &

Hudson, 1995, p. 47. - Memory related in A Night to Forget by Renée Harris, 1964 typed manuscript, Lord-MacQuitty Collection, National Maritime Museum, London, p. 1. Thanks to Shelley Binder for providing a copy. Titanic’s sister ship Olympic held a July 4th dancing party attended by many notable passengers in 1911. But this was an unusual event on a British ship. Thanks to Mike Poirier for furnishing this clipping.

- Post, Emily, Etiquette, New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1922, p. 603.

- The Truth About the Titanic by Col. Archibald Gracie in: Winocour, Jack, ed., The Story of the Titanic as Told by its Survivors, New York: Dover Publications, 1960, pp. 121-122; William Sloper’s Account of the Titanic Disaster, Encyclopedia Titanica, 2001. Contributed by Mike Poirier.

- Candee, Helen Churchill, Sealed Orders, Collier’s, May 1912, p. 10.

- Post, p. 603.

- Ibid; Holt, Emily, The Encyclopedia of Etiquette, New York: Doubleday, Page and Co., 1916, p. 450.

- Rittenhouse, Anne, A Sea-Faring City, Vogue, September 15, 1913, pp.33-34: other fashion articles opined on the dress of voyagers, including: What She Wears, Vogue, May 15, 1912, p. 37 and A Sea-Going Wardrobe, Vogue, June 15, 1913, pp. 64-65.

- Post, p. 603; Holt, Emily, The Encyclopedia of Etiquette, New York: Doubleday, Page and Co., 1916, p. 449.

- Rittenhouse, Anne, A Sea-Faring City, Vogue, September 15, 1913, pp.33-34

- Ibid

- Ibid; Holt, Emily, The Encyclopedia of Etiquette, New York: Doubleday, Page and Co., 1916, p. 449.

- Archbold, Rick and Dana McCauley, Last Dinner on the Titanic, Toronto: Madison Press, 1997, p. 12.

- May Futrelle in the Seattle Daily Times, April 22, 1912.

- May Futrelle in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 28, 1912.

- May Futrelle in the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, April 29, 1912.

- Harris, René, Her Husband Went Down With the Titanic, Liberty, April 23, 1932, pp. 27-28. Rene’s arm injury was mentioned in Helen Candee’s May 1912 Collier’s article (cited elsewhere in these notes) and in Fifth Officer Harold Lowe’s testimony at the American Titanic Inquiry, April 24, 1912. Rene’s sleeveless dress on April 14th may have been designed by the French house of Martial et Armand. A 1912 letter from the firm exists in a scrapbook belonging to Harris in the Theatre Collection of the Museum of the City of New York.

- Dorothy Gibson in the New York Morning Telegraph, April 21, 1912. Dorothy’s gown may have been a Poiret design; Titanic researcher Olivier Mendez recorded that Dorothy bemoaned the loss of Paul Poiret dresses in her luggage to fellow survivor Fernand Omont (Correspondence with the author, July 13, 2018). Dorothy’s financial claim against the White Star Line specified no designer names.

- Rosenbaum, Edith, The Wreck of the Titanic, Cassell’s, June 1913, p. 35. Edith never cited the maker of her dinner dress but her claim for recovery of the cost of her lost wardrobe trunks included the names of top Paris fashion houses, including those of Paquin, Bernard, Georgette and Reboux; Claim of Edith L. Rosenbaum, 1913: In the Matter of the Petition of the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company, Limited, for Limitation of its Liability as owner of the steamship Titanic; Admiralty Case Files, 1790 - 1966; Records of District Courts of the United States; National Archives, New York, NY.

- Rittenhouse, Anne, A Sea-Faring City, Vogue, September 15, 1913, pp.33-34.

- McElroy, Frankie, Death of a Purser, UK: AuthorHouse, 2011, p. 33.

- Claim of Charlotte D. M. Cardeza; 1912: In the Matter of the Petition of the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company, Limited, for Limitation of its Liability as owner of the steamship Titanic; Admiralty Case Files, 1790 - 1966; Records of District Courts of the United States; National Archives, New York, NY.

- Claim of Marian L. M. Thayer, 1913: In the Matter of the Petition of the

Oceanic Steam Navigation Company, Limited, for Limitation of its Liability as owner of the steamship Titanic; Admiralty Case Files, 1790 - 1966; Records of District Courts of the United States; National Archives, New York, NY. - Bigham, Randy Bryan, A Matter of Course, Encyclopedia Titanica, 2005; Claim of the Countess of Rothes, 1913: In the Matter of the Petition of the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company, Limited, for Limitation of its Liability as owner of the steamship Titanic; Admiralty Case Files, 1790 - 1966; Records of District Courts of the United States; National Archives, New York, NY.; Lord, Walter, A Night to Remember, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1955, p. 46; Madeleine Astor’s dinner attire that night was apparently the same outfit she wore in the lifeboat in which she escaped, No. 4. (Chicago Examiner, April 20, 1912)

- Memories related to Shelley Dziedzic by Marjorie Newell Robb, c. 1987. My thanks as well to Mike Poirier.

- Candee, p. 10-11.

- Duff Gordon, Lucy (Lady), Discretions and Indiscretions, New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1932, p. 165.

- Page from Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon’s lawyers’ estimation of damages, as reproduced in The Daily Telegraph (London), April 14, 2012.

- Margaret Brown in The Newport Herald, May 28, 1912.

- Margaret Brown in the Rocky Mountain News, April 30, 1912. According to Walter Lord, Margaret was “stylish in a black velvet two-piece suit with black and white silk lapels” on the last night, as cited in: Lord, Walter, A Night to Remember, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1955, p. 46; the brooch that was later reported stolen was described in the New York Evening World, September 4, 1921.

- Klistorner, Daniel and Charles Provost, Elusive Passenger Pens Story, Voyage, Spring 2008, p. 132.

- Several female Titanic passengers were smokers, including Lucy Duff Gordon and René Harris. The previous year, Lucy told reporters, “All chic women smoke. Only the old frumps and those it makes sick are the exceptions.” (New York Daily People, May 25, 1911). And René Harris had in her Titanic luggage a gold cigarette case as cited in: Bigham, Randy Bryan and Gregg Jasper, Broadway Dame, Morrisville, N.C.: Lulu Inc., 2019, p. 50.

- Rittenhouse, Anne, A Sea-Faring City, Vogue, September 15, 1913, pp.33-34

- Ibid.

(The Vogue Archive)

Comment and discuss