The Carpathia had a lot of passengers aboard, but they were wonderful. They did all they could for us.

Maude Sincock, Second Class survivor

The passengers offered the survivors their staterooms. There was no distinction between the First Cabin passengers and the women of the Steerage. All were treated alike with the same kindness and human sympathy.

Lily May Futrelle, First Class survivor

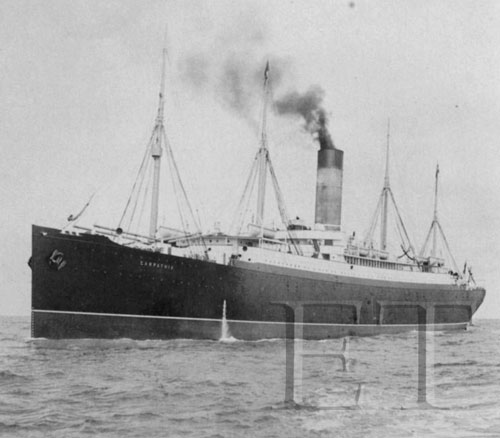

On April 11th, as the Titanic travelled ever further from the Irish coast, on the opposite side of the Atlantic, the much smaller Carpathia was preparing for a scheduled sailing to the Mediterranean. Just four days later, Captain Rostron would order his ship turned, as news that the Titanic was sinking was received by Harold Cottam, the ship’s wireless operator. The ship’s crew would be directed towards making preparations for the rescue of over 2,000 people. The ship's 743 passengers were initially ignorant of the events taking place, with orders being passed to stewards that anyone disturbed by the preparations was to be sent back to bed. Yet, there can be no doubt that when the Carpathia came to the rescue of the survivors of the Titanic, her passengers did all they could to relieve suffering and distress. Many survivors recalled how the passengers of the Carpathia gave up their staterooms, clothing and toiletries, while others worked to provide refreshments for the rescued, and to revive those suffering from cold and exposure. But, in spite of their deeds, these people remain largely anonymous, their names forgotten.

The Carpathia departed New York on April 11th carrying 743 passengers; 128 in first class, 50 in second class and 565 in third class. The winter in America had been a hard one, and spring had been late in arriving.

Carlos Hurd recalled in later years how even as late as Easter Sunday the snow had lain on the lawns of the homes of St. Louis. Weather reports in Chicago forecast brisk winds, while further south the outlook was cool, cloudy and wet. Many of those travelling in First and Second Class were using the Cunard steamer to escape the poor spring weather to travel to warmer climates and begin holidays abroad. For those travelling Third Class the trip was more than just an opportunity to escape the cold American winter. These people were looking forward to revisiting family in their former homes.

For First Class passenger Reuben Weidman the trip was a spontaneous one. Mr Weidman, a photographic engraver from Albany, New York, had only ever planned to see off friends, Lucius and Emma Hoyt, who were sailing on the Carpathia to begin a holiday touring Europe. But when he reached the station in Albany the couple prevailed on him to join them, as he had in the past. Weidman decided almost at once to join the couple, and hurried home to quickly pack and rejoin them on the train. Weidman was a 63 year old widower. He had begun his working life as a store clerk for his uncle and had gradually progressed to owning the business. In 1890, Reuben married Helen Hunting. The couple raised a single daughter, by 1912 Mrs Caroline Sominic, with whom Reuben lived.

Other passengers' preparations were more thorough. Carlos and Katherine Hurd had planned their trip carefully. Hurd was a reporter for the St. Louis Post Dispatch. A graduate of Drury College, Springfield, Missouri, Hurd had worked for the newspaper for almost twelve years, and had secured a two month leave of absence. The couple planned to sail to Naples, and then see Europe, but before the holiday could begin Carlos had endeavoured to achieve a personal goal, and meet newspaper man, Charles Chapin, editor of the New York Evening World. To that end Carlos and Katherine arrived in New York a day early. The meeting, though brief, realised Hurd’s dream, but was tinged with disappointment. Hurd barely had time to tell Chapin that he was to sail on the Carpathia before the interview was over.

Emma Hutchison was another passenger who had made certain preparations before embarking on the Carpathia. For Emma the excitement of sailing day was just another highlight in a very busy few days. Emma was one of several newlyweds to sail on the Carpathia on April 11th. Her husband, Charles Milton Hutchison was an architect, and had presented his bride with a platinum pendant set with diamonds and pearls. Emma, conscious that she would have desired to wear her new treasure, but fearing for its safety while travelling had decided to leave it behind together with her engagement ring. From the Carpathia she wrote to her friend, Mabel Dalby, thanking her for the cards that had reached the ship, and the keepsake of a handkerchief.

Couples like Emma and Charles Hutchison, age 31 and 27 respectively, and Carlos and Katherine Hurd dispelled the image created by Walter Lord in A Night to Remember that the Carpathia was carrying, at least in first class, ‘mostly elderly Americans following the sun.’ Emma and Charles Hutchison were one of several honeymoon couples on the little steamer. Howard Chapin, age 24, had married Hope Brown, age 27, in Providence, Rhode Island on April 10th. Hope was the daughter of a former state governor. Her husband a jeweller and assistant business manager for the Providence Evening News. Their invited guests included the society of Providence, among them the Ostby family, who had declined their invitation on account of being abroad.

Howard and Hope Chapin

Courtesy of Michael Poirier

James Arnold Fenwick, a Canadian by birth, age 38, had just married 33 year old Mabel Sanford in Kentucky. Mabel was a daughter of Strother Sanford, a successful farmer, and was 33 years old. Her new husband was a real estate man, and the son of a hardware merchant from Quebec. The couple had booked cabin A21 on the Carpathia, just under the boat deck, and a few cabins down from Howard and Hope Chapin.

Courtesy of Michael Poirier

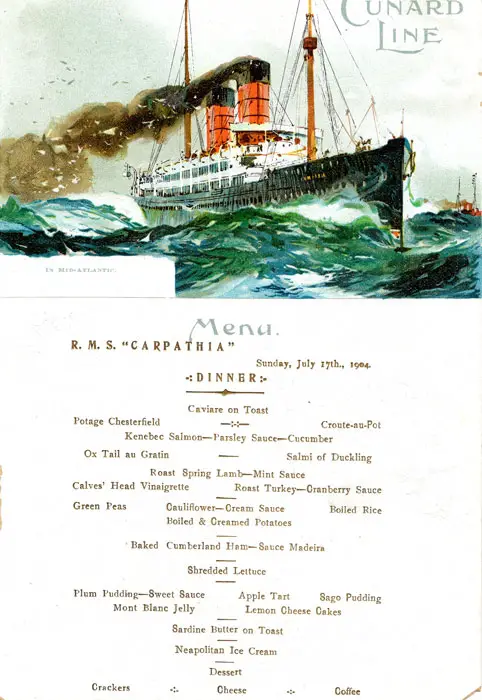

The early days of the voyage were uneventful, but for the intense cold, remarked upon by both passengers and crew. Katherine Hurd wrote to her sister confiding, “there is not a great deal happening on ship”. Passengers could enjoy fine food, socialise with each other, enjoy shipboard games or while away the time on deck. Mabel Fenwick explored with her camera, snapping shots of the crew at work and leisure, while her husband took a picture of his bride enjoying shipboard games. But the weather stayed cold, forcing many to remain indoors. Here they could play cards, read, write letters home, or listen to the Carpathia’s orchestra. Two members of this small group had recently left the Carpathia. Roger Bricoux and Theodore Brailey had transferred to the Titanic. In first class Emma and Charles Hutchison enjoyed meeting new people. They shared a table in the saloon with Charles and Olga Iddiols. Mr and Mrs Iddiols were from St. Louis where Charles was vice-president of a cloak factory. Husband and wife were both from humble beginnings, the children of immigrants. Charles’ father had been a blacksmith, originally from England, while Olga was the daughter of a coal dealer.

They, and other passengers could not believe that Charles and Emma were on honeymoon, and Emma Hutchison put this down to the experiences that she and ‘Hutch’ had been through. Carlton Phelps, from North Adams, Massachusetts, was sure the couple must have children. Phelps, a justice of the court of North Berkshire, Massachusetts, the president of the North Adams Savings Bank, and the vice president of the Richmond – Wellington Hotel, had left his two children, Christine, age 25, and Gordon, age 14, in America to embark on a holiday with his wife, Virginia, and friends, William and Sarah Pritchard. William Pritchard worked for a bank in North Adams, and he and Sarah, like their friends, had two children, Herbert and Margaret, who were close in age to Christine Phelps.

Not every passenger settled to shipboard life quickly. Annie List, travelling to Budapest, was troubled by seasickness for the first few days. She was confined to her cabin and found the voyage very trying.

On Sunday April 14th the day dawned bright and clear, a change to the overcast skies that had accompanied the voyage so far. It being Sunday, at half past ten in the morning Captain Rostron conducted Divine Service for the first class passengers. Many members of the crew attended the service, a sight that Mabel Fenwick said was ‘most impressive’. In the afternoon the weather turned warm and sunny, and people took advantage of being able to sit out on deck. But it became so warm later that Howard and Hope Chapin, who had already laid aside their coats and steamer rugs, asked the deck steward to move their steamer chairs to a shadier spot. Howard Chapin noticed that a number of men were sitting in just shirt sleeves.

In the late afternoon Josephine Marshall, who was travelling to Europe with her husband, Charles, and daughter, Evelyn (pictured right), sent a message to her nieces who were passengers on the Titanic. The women, Mrs Appleton, Mrs Brown and Mrs Cornell, were returning to America following the funeral of their sister in England. Charlotte Appleton replied to her aunt’s message, wishing the family love. Charles Marshall was one of the oldest passengers on the Carpathia. Born in New York in 1845 he was 67 years old, and some sixteen years senior to his wife, Josephine. The couple and their daughter were one of the few first class families to be travelling with servants, a French maid for the ladies and a Swedish valet to attend to Mr Marshall. The family were travelling to their home in Paris.

Charles Marshall’s father had founded the Black Ball Shipping Line, running packet ships from Liverpool to the United States. After graduating from Columbia University in 1858, followed by a grand tour, Charles joined the company, becoming general manager by 1865. Marshall was a shrewd businessman, but also a keen supporter of civic affairs. He had served as a commissioner at the World’s Fair in 1876, and a New York Harbour commissioner. By 1912, with his health failing, Charles was retired, and divided his time between Europe and New York.

Just a few years older was William Henry Harrison Johnson. Born in Elkhorn, Wisconsin in February 1840, William was 72 years old, and was travelling with his son, Nason Collins Johnson. William had been educated at Oberlin College and had spent his working life as a banker. But it was a personal tragedy that brought him on board the Carpathia. On March 14th 1912, Johnson’s wife of thirty-nine years, the former Mary Nason, died. To help his father recover from his loss, Nason Johnson had suggested a Mediterranean trip.

After a warm and sunny afternoon, the evening sky remained clear, but it became cold. Dr Frank Blackmarr, a radiologist from Chicago, took a stroll on deck before retiring. The night seemed so dark, and the stars shone brightly. Blackmarr was glad that he had with him a warm overcoat. A graduate of Hahnemann Medical College, he was travelling second class to Gibraltar, accompanied by the son of a neighbour, Cecil Francis. Cecil, age 15, was the son of a magazine publisher.

Howard and Hope Chapin retired after a final walk on deck at around 10 o’clock. As they left the deck Howard noticed that there was a lifeboat directly above the cabin. A cleat held the boat by a painter to the deck. The boat was the only one on that side of the deck to be swung outwards.

As April 15th arrived, most of the Carpathia’s passengers slept. Yet for many their sleep was soon to be disturbed by unusual sounds in the dark, as shortly after midnight the Carpathia received the news that the Titanic was sinking. Immediately, Captain Rostron ordered the ship turned.

In his upper berth Howard Chapin was woken by a noise. Howard quickly realised that the noises were being made by someone working at the lifeboat above the cabin, and he reasoned that something must be wrong with the ship. He hurriedly woke his wife, and then pulled on a coat and went on deck to speak to the man. The sailor explained that the Carpathia had received a wireless message from the Titanic, saying that it had struck an iceberg and was sinking. The sailor went on to say that the Carpathia was rushing to the Titanic’s assistance. Howard looked about him. The night was bitterly cold, but the sea was calm, with no swell. He went back to his cabin and told Hope the news. They both dressed warmly and went on deck.

Nearby, Augusta Ogden had also been disturbed by voices and noises overhead. Augusta and her husband, Louis, were from Manhattan, where Mr Ogden was a lawyer. They also had a home in Tuxedo Park, New York, and were travelling to Europe for a holiday much as their Tuxedo Park neighbours, the Frederic Speddens, had done so months earlier. Mrs Ogden woke her husband, who observed that the sounds were those made by a lifeboat being swung out. When he looked out of the cabin into the corridor he saw a line of stewards carrying blankets. Unlike Howard Chapin, Mr Ogden found it hard to learn what was going on. Dr McGhee, the Carpathia’s surgeon, admitted that there had been an accident, but not to the Carpathia, and insisted that the couple should return to their cabin. Ogden was by that time convinced that the Carpathia was in danger, and asked a quartermaster for more information. The quartermaster answered truthfully, but Ogden found it hard to believe that anything could be wrong with the Titanic, and remained skeptical about the safety of the Carpathia, saying, “You’ll have to give me something better than that. The Titanic is on a northern route, and we are on the southern.” Exasperated, the quartermaster retorted, “We are going north like hell!”

Dr McGhee was less discrete when he spoke to Mrs Charles Crain. Mrs Crain was the wife of an officer in the US Army, and with her husband and daughter was travelling to Europe. Anna Crain, age 35, and her husband, age 39, were one of just two families travelling first class to have a child with them, Elizabeth, age 11. Captain Crain was unwell during the voyage, and on April 15th he woke needing the doctor’s care. Charles woke his wife, who, as she summoned Dr McGhee, puzzled over the smell of coffee brewing. The Carpathia was usually quiet at this time of night, and the activity was out of the ordinary. When Dr McGhee arrived around 1.30, he told the couple that word had come by wireless that the Titanic was sinking. Mrs Crain dressed and went on deck. With her she took a pair of binoculars.

Cecil Francis and his companion, Dr Blackmarr, learned the news direct from Carpathia’s wireless operator, Harold Cottam. Cottam had become acquainted with the men during the voyage, and at some point found time to go to their cabin and give them the news. Both hurriedly dressed and went on deck.

Dr C.A. Bernard learned the news in the First Class Smoking Room. Bernard had taken to watching the ship’s radio antennae flashing and snapping in the darkness, and instead of going to bed made his way from the deck to the smoking room at around midnight. He had not been there for long when a white-faced steward hurried in seeking the second officer. Moments later Captain Rostron, in a shirt and bathrobe, passed through. Not long after Bernard heard that the Titanic had sounded S.O.S.

All around crew members prepared the vessel for the job of rescue. Mrs Crain was impressed by the speed of the work; it was as if the crew were taking part in some ordinary drill. Charles and Hope Chapin found the deck scattered with the paraphernalia of rescue; breeches buoys, lifebelts, and blankets, while along the side of the Carpathia were hung rope ladders.

Charles and Emma Hutchinson waited until after 3 o’clock to investigate the sounds that had been keeping them awake. Finally Hutch told his wife, “What’s all this about? I am going to get up and see, as I have heard it long enough”.

Louis and Augusta Ogden

Courtesy of Michael Poirier

As the Carpathia neared the scene of the accident, more and more of her passengers became aware that something was wrong. Mary Lowell was roused by the noise of someone passing her cabin, and heard the words ‘iceberg’ and ‘sinking’. When she arrived on deck people were pointing and shouting at a flickering light in the distance. Miss Lowell realised that she had been woken by the increased vibration of the ship, which was racing through the ocean. May Birkhead was woken by footsteps above. She dressed and arrived on deck as dawn was breaking. Emma Hoyt woke because the ship’s movement had stopped. When her husband put his head out of the cabin a passing steward told him the ship had stopped to rescue survivors from the Titanic. Mabel Fenwick, who had been woken by a man’s voice crying, “Titanic’s going down!” recorded the rescue with her camera, as did fellow passengers, Bernice Palmer and Lewis Skidmore. Augusta Ogden only thought of her camera after Captain Rostron prompted her. Rostron was standing near the couple on deck, supervising the rescue. Seeing Mrs Ogden he reminded her that she had a camera with her, and suggested that she fetch it.

May Birkhead, Wallace Bradford

And it was a scene worthy of recording. May Birkhead arriving on deck was “greeted with a most beautiful sight of icebergs on every side – some of much greater dimensions than the ship, and then some baby ones – all beautiful white in the calm sea and glittering sun, a most impressive view.” Wallace Bradford noted that it was a “glorious, clear morning and a quiet sea. Off to the starboard was a white area of ice plain, from whose even surface rose mammoth forts, castles and pyramids of solid ice.” Mrs Carlos Hurd was momentarily blinded by the sudden glare of light on the ice-field, and then she noticed the lifeboats. It was her “first realisation of the great tragedy.”

Others quickly noticed the lifeboats now making their way towards the Carpathia. Mary Lowell felt the creeping boat would never reach the ship, while Lucius Hoyt described how the boats appeared out of the dark of the dawn, first one and then another. Hoyt noted that sometimes a cake of ice was mistaken for a boat. Miss Meta Fowler was one of the Carpathia’s passengers who commented on the wreckage. She observed very little, just a few pieces of wood and other materials. It did not seem possible to her that these few hundreds could be the victims of a shipwreck. Like many of the Carpathia’s passengers, she observed how much in readiness the Cunarder was, and how simply and rapidly the survivors were taken on board. Mary Lowell noticed that many of the women were so cold that it was a struggle for them to manage the rope swings let down to rescue them, and how they seemed to stagger into the arms of people on the ship when they reached the deck. Lucius Hoyt felt that discipline on the Carpathia was marvellous so that survivors could be received without “fuss and frather”.

Louis Ogden was soon recognised by one of the survivors. As he watched people arrive he was greeted by Henry Sleeper Harper of the publishing family. Harper exclaimed, “Louis, how do you keep yourself looking so young?” Other survivors found unexpected friends among the Carpathia’s passengers. Helen Ostby was quickly found by Howard and Hope Chapin. They took her, and Mrs Warren, to their cabin. Wallace Bradford recognised Washington Dodge and his family, who like him, were residents of San Francisco. Bradford and his wife, Agnes, offered their stateroom to the family. Before leaving San Francisco Bradford had spoken to a group at the Monroe School, his talk entitled, ‘Strange Sights I Saw on a Trip Around the World.’ Juliet Tarkington was watching the rescue work with her mother, sister, aunt and uncle, when she spotted a familiar face in one of the lifeboats. A graduate of Quincy Mansion School in Boston, Juliet spotted fellow schoolmate Gretchen Longley.

Anxiously searching the survivors was John Badenoch of Manhattan. Badenoch was head of the grocery department at Macy’s Department Store, and was bound for Europe on a buying trip. Hearing that the Carpathia was to assist the Titanic, Badenoch arranged to give up his stateroom to Isidor Straus, the owner of Macy’s, who had been on the Titanic with his wife, Ida. Also searching was Charles Crain, the captain in the American Army. For some years he had been acquainted with Major Archibald Butt. Crain was able to learn from survivors that Butt had behaved admirably, and that like Mr and Mrs Straus, he had down with the ship.

For Josephine Marshall the news of the Titanic’s loss, and the Carpathia’s night time dash came in rather and unusual way. The Marshall family had slept through the drama, and were woken early on April 15th by a steward knocking at their door. The steward explained that Mr Marshall’s niece wished to speak to him. Marshall was confused, explaining to the steward that his nieces were on board the Titanic. Quickly the steward explained what had happened, and shortly afterwards Josephine and her husband were united with Charlotte Appleton. Her cousin, Evelyn Marshall, hurried on deck to see what was happening, while the rest of the family waited for Mrs Appleton’s sisters to be brought to the Carpathia.

Again and again during the hours of rescue the Carpathia’s passengers were struck by the calmness displayed by survivors, and the quiet. Stanton Coit, president of the West London Ethical Society travelling to America to give a series of speeches on women’s suffrage, noted, “My first and lasting impression was the inward calm and self poise - not self-control, for there was no effort or self consciousness – on the part of those who had been saved.” Maurice McKenna, travelling second class with his wife, daughters and grandchildren gave up his stateroom to Mrs West and her children. Little Constance West asked Mr McKenna for a pencil and paper so that she could write to her Daddy to ask what was keeping him. Dr Bernard was moved to tears by the bravery of the women survivors, noting that their eyes “seemed to blaze with horror and mute appeal in the growing dawn.”

Lawrence Stoudenmire, a young man from Baltimore who was travelling as a chauffeur to four spinster ladies, felt that listening was the most important thing that anyone of the Carpathia could do. “All of us listened while they talked. I think it was good for them.”

The survivors may have been mostly calm, but Emma Hutchison was one of a number of people on the Carpathia who commented on the number of dogs saved. Emma had an ‘insane desire’ to kick them.

With the rescue complete, the Carpathia cruised the area, before setting course for New York. On board her passengers and crew sought to care for the rescued. Many gave up their rooms to the Titanic’s people. Mary Lowell, travelling with her mother, offered their cabin to actress and model, Dorothy Gibson, while Luke Hoyt and his wife moved in with Charles and Lucy Reynolds, so that four male survivors could take their room. Charles Spielman provided Frederic Spedden with a berth, while Louis and Augusta Ogden offered other members of the Spedden family shelter. John Badenoch, knowing now that Mr and Mrs Straus were lost, turned to assist four buyers, providing them with ‘limitless quantities of bourbon’ to ward off the cold, and a place to rest. Mrs Lucien Smith, whose husband had died on the Titanic, was taken in by James and Monnie Shuttleworth. Elderly William Johnson insisted that he also give up his berth to survivors, offering it to Elmer Taylor. Taylor was reluctant to accept until another Carpathia passenger offered to share his room with Mr Johnson. Taylor, his wife, and Mrs Crosby and her daughter, then took the cabin.

When Dr Frank Blackmarr tried to insist that an elderly lady take his room, she declined, saying that there others in greater need than she was. Instead, a woman who turned out to be a governess, and who was sitting beside a large women, grabbed Dr Blackmarr by the arm and insisted that the large woman be given the birth. Blackmarr tried to lift this larger woman into the upper berth, but three times failed. Two women in the room who had lost everything began to see the humorous side of things, and one suggested that Blackmarr ‘put her up’ like a footballer making a tackle.

For one of the Carpathia’s passengers there was a more solemn and tragic task to perform. Several people had been taken from the Titanic’s lifeboats dead, and Father Roger Brooke Taney Anderson, an Episcopal priest from Baltimore, now performed the last rite and a service that would commit the bodies to the sea. The service took place at 4.00 o’clock in the afternoon, almost twelve hours after the first lifeboats had been recovered. Charles Hutchison watched the funerals. A door in the side of the Carpathia was opened, and a gangway was let down. The bodies were lowered to this platform and were covered with a British flag before they were uncovered and carefully pushed off, making as little splash as possible. Only one struck the water flat with a noise that Hutchison knew he would never forget.

The Carpathia was now overcrowded, with space and supplies at a premium. Nevertheless, Wallace Bradford observed that the meals were “almost as good shape as they were before the Titanic passengers came aboard, and everybody connected with the ship, from the captain to the scullery boys, is doing his utmost to handle the passengers which overcrowded the steamer. Beds have been made up on the tables in the dining saloons, and the women who have not been able to find berths in staterooms are occupying these beds, while the men who were occupying berths on the Carpathia have turned them over to the rescued passengers and are sleeping in the hallways and smoking rooms of the steamer.” Mary Fabian, from Chicago, commented, “My room was full all day of people who wanted to dress or lie down, or arrange their hair.” She observed that on the first day after the rescue the meals on the steamer had been confused, but these early problems and inconveniences were quickly overcome.

During the voyage to New York, as the survivors of the Titanic told and retold their experiences to the Carpathia’s passengers and crew, there were a number of people who were associated with newspapers. For them, and others, this was an opportunity not to be missed; an exclusive that the wider world was crying out to hear. However, Captain Rostron, anxious that the people in his care should not be bothered by the press, placed an embargo on the sending of stories by wireless. Initially, this was an empty threat as the ship’s wireless was too weak to communicate with the shore, but Rostron foresaw that as soon as the ship was in range it would be besieged by the newspapers. Carlos Hurd, the reporter with the St. Louis Post Dispatch, quickly realised the position he was in, and used all the ingenuity he possessed to collect his story, and keep it safe for publication in New York. He hoped that his meeting with Charles Chapin only days earlier had not been forgotten by the editor. He need not have worried. As soon as Chapin heard that the Carpathia had been involved in the rescue he remembered that Hurd was on her. The difficulty that both men could see was how to get the story to the land. Chapin solved that problem. As the Carpathia entered New York, Hurd was able to throw his story to Chapin who had come alongside the Carpathia in a boat.

May Birkhead was another passenger who managed to get her story, and sold it to the New York Herald. Miss Birkhead was travelling with her aunt, Miss Sue Eva Rule. The ladies were from St. Louis, where May had established a reputation as a skilled needlewoman. Her success had enabled her to pay her own way on the trip. Miss Birkhead was on deck to see the picking up of the Titanic’s lifeboats, although her aunt slept through the initial drama, and woke to see a lifeboat making its way to the rescue ship. Momentarily confused, Miss Rule thought the ship had stopped to rescue the crew of an airship which had crashed. For Miss Birkhead the experience was enough to enable her to continue to work as a journalist, and during the First World War she covered news from France.

Despite a willing spirit on the part of the Carpathia’s passengers and crew to assist the survivors in every way, the voyage to New York was trying and emotional. Mrs Timothy Hardgrove, the daughter of Maurice McKenna, wrote to her family to say that after all they had seen the party had “all lost courage.” The ship had ridden through stormy weather, a thunder storm on April 16th, and more rain on April 17th. Mrs Hardgrove added that it was difficult to write as she was sitting out on deck in the rain. Annie List, who had suffered seasickness in the first days of the voyage confessed that she had no wish to “cross the ocean very soon again.” Reuben Weidmann felt much the same, “I have had all I want and now have one desire – to get back to Albany and try to forget those heart-rending scenes witnessed among the unfortunate who lost their loved ones on the Titanic”.

Mrs Lewis Skidmore, Philip Mauro, Carlos Hurd

The Carpathia’s role in the Titanic story came to an end with her arrival in New York on April 18th. Her passengers, whose voyage had been interrupted, left the ship while arrangements were made to clean and replenish the vessel for a sailing on April 20th. The passengers used the interval to replenish their own possessions. Lewis Skidmore had to buy fresh shirts and collars, as his own had been given to survivors, while Philip Mauro sought new toothbrushes. May Birkhead reached the offices of the New York Herald and filed her story, as did second class passenger, Fred Beachler, who had worked as a compositor on the paper for several years. Lewis Skidmore, his shopping complete, provided the Brooklyn Daily eagle with photographs he had taken of the rescue.

On April 20th 1912 the Carpathia once more departed New York for the Mediterranean. On board were most of her original complement of passengers. Just sixteen people had chosen not to reboard the ship; twelve first class passengers and four second class passengers, but a further eight had engaged passage, including Mrs Catherine Blackmarr, who had travelled from Chicago to meet her husband on April 18th, when the Carpathia arrived with Titanic’s survivors.

As the Carpathia set sail again for Europe her passengers faded back into obscurity; their role in the Titanic disaster forgotten amidst the stories of horror and heroism as the Titanic sank. Life resumed a regular routine, and the threads of holidays and homecomings were once more picked up. Time moved on, and when these people returned to America in the summer and autumn they simply resumed their everyday lives. Forgotten, until now.

A word about the Carpathia’s passenger list.

The Carpathia’s first class passenger list was printed in the New York Times on April 19th 1912, and while it does give an idea of who sailed on the Carpathia from New York on April 11th, it is also a list that is riddled with errors. But then it is not alone. When he disembarked from the Carpathia, Titanic survivor Jack Thayer took with him a copy of the Carpathia’s passenger list. This list, compiled around the time of sailing, is similar to the list in the New York Times. Again, it is a list complicated by mistakes, from the simple confusion of Miss and Mrs, to the complete mis-listing of some passengers. A good example is that of May Birkhead, who was travelling with her aunt. Both ladies are listed as the Misses Birkhead, rather than as Miss Birkhead and Miss Rule. Similarly, Miss Juliet Tarkington is listed as Miss J. Shuttleworth. The reason, Juliet was travelling with her aunt and uncle, Mr and Mrs James Allen Shuttleworth.

Acknowledgements

The original of this article appeared in the Atlantic Daily Bulletin, the journal of the British Titanic Society. This new version has been significantly rewritten as new information has come to light in the last few years. I am indebted to George Behe for his support of my Carpathia research. His book, The Carpathia and the Titanic, available from Lulu.com is indispensable for those wishing to understand more about the role of the Carpathia in the Titanic story.

Comment and discuss