“It was perhaps the most catastrophic lapse of memory in history, costing more than 1,500 lives. A sailor called David Blair forgot to leave behind a key as the Titanic set off on its maiden voyage. Without it, his shipmates were unable to open a locker

With a further reference to “the key which may have saved the luxury liner,” so ran a story on the website of the London Evening Standard on January 16, 2007,1 continuing one of the most famous “what if” stories in Titanic history. This oft-repeated tale holds that a pair of binoculars designated for the lookouts’ use had been placed in a cabinet in the officers’ quarters with the key held by David Blair, the former Second Officer who lost his place on the ship in a last-minute shuffle of officers. According to the story, Blair had the key in his pocket, and following his departure no one knew where the binoculars were. For want of a key the ship was lost - or was it? As we will see, there are a number of misconceptions, misunderstandings and blatant inaccuracies surrounding this popular belief, and in reality, Titanic’s fate did not turn on a set of missing binoculars.

The above story most likely has its origins in testimony by lookout George Hogg following the sinking. Hogg testified at the British Inquiry that on the trip from Belfast to Southampton, the lookouts had been loaned by Blair a pair that were marked “SECOND OFFICER, S.S. TITANIC.” Upon Titanic’s arrival at Southampton, Blair had been in the crow’s nest using the binoculars himself. (When docking the ship, each officer had an assigned station, and the crow’s nest position was assigned to the Second Officer.) Hogg was asked:

17501. When you left the ship at Southampton, what did you do with those glasses?

Mr. Blair was in the crow’s-nest and gave me his glasses, and told me to lock them up in his cabin and to return him the keys.

17502. Who returned the keys?

I gave them to a man named Weller2, as I was busy on the forecastle head.3

17503. As far as you were concerned, the glasses, you were told, were to be locked up in the cabin

of the second officer?I locked them up.

Much was made of this story in August of 2007, when the auction firm of Henry Aldridge & Son announced that this key would be made available for bid,4 having come to them from the British and International Sailors Society, to which the key had been left by Blair. (Also auctioned was a postcard written by Blair to his sister expressing his regret at missing Titanic’s sailing.) However, as we shall see, this missing pair of binoculars had nothing to do with the collision with the iceberg. It’s also likely that the missing pair had nothing to do with binoculars not being provided to the lookouts after Southampton.

Having been provided with a pair for their use on the trip from Belfast to Southampton, the lookouts expected that they would have them available for the next leg of the voyage. Lookout George Symons stated that, “After we left Southampton and got clear of the Nab Lightship, I went up to the officers’ mess-room and asked for glasses. I asked Mr. Lightoller, and he went into another officer’s room, which I presume was Mr. Murdoch’s, and he came out and said ‘Symons, there are none.’ With that I went back and told my mates.” (B11324)5

Blair’s replacement as Second Officer was Charles Lightoller. His version of the event, although differing in a few minor details, bears out Symons’ story: “I was in my room, and I heard a voice in the quarters speaking. I recognized it as Symons, the look-out man, so I stepped out of my door, saw him, and said ‘What is it, Symons?’ He said, ‘We have no look-out glasses in the crow’s-nest.’ I said, ‘All right.’ I went into the chief’s6 room, and I repeated it to him. I said, ‘There are no look-out glasses for the crow’s nest.’ His actual reply I do not remember, but it was to the effect that he knew of it and had the matter in hand. He said that there were no glasses then for the look-out man, so I told Symons, ‘There are no glasses for you.’ With that he left.” (B14485)

According to Lightoller, there were five pairs on board: “A pair for each Senior Officer7 and the Commander, and one pair for the Bridge, commonly termed pilot glasses.” (B14327) Even if the whereabouts of the Second Officer’s pair was unknown, another pair could have been loaned to the lookouts if had they been deemed a necessity – but as we shall see, they were not.

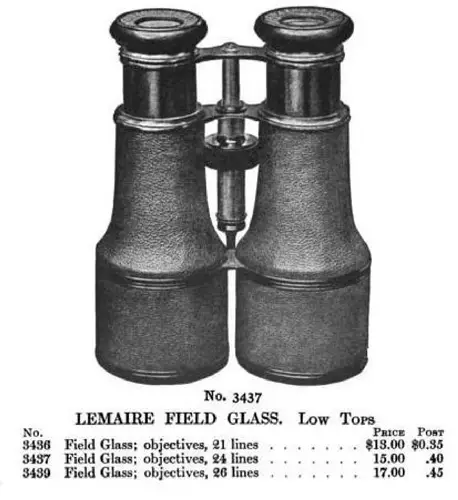

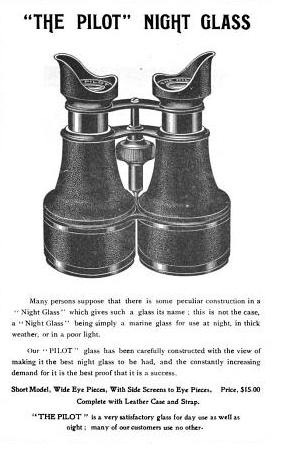

(Catalogue of Riggs & Brother, Philadelphia, 1902, p. 137)

At sea with a normal watch on the Bridge, only one pair was normally required and in use at any given time. This was the pair carried by the officer of the watch, this being either the Chief Officer, First Officer or Second Officer. No other officer on duty would have needed them.8 But what should perhaps be obvious here is that there was no pair specifically designated for the use of the lookouts or for the crow’s nest.

Much was also made of a box in the crow’s nest – a small box in the port after corner (B11325) that could be used to hold binoculars. One of the enduring misconceptions in Titanic history is that this proves that binoculars were intended for the crow’s nest. In fact, they were not. The question was put to Charles

Bartlett, Marine Superintendent of the White Star Line, at the British Inquiry:

21715. (Mr. Scanlan.) Why have you a bag or a box in the crow’s nest to hold binoculars if you do

not think they are required?That was not always for binoculars; that was for anything the men used in the look-out.

21716. It was not always for binoculars, but it was for anything a man might use on the look-out,

you say?Yes.

21717. What do you mean by that?

His muffler, his clothes, and his oilskin coat and that sort of thing. There is generally a canvas bag put up there.

In order to understand why binoculars were not provided as standard equipment, we need to delve into

some of the post-sinking testimony as to how the utility of binoculars by lookouts was regarded in 1912. When

we do so, we find that there appears to be a great difference of opinion. Not a single captain voiced an

opinion in favor of them, and some were quite outspoken against them:

Do you think it is desirable to have them?

No, I do not.

Captain Richard Jones, Master, S.S. Canada (B23712)We have never had them.

Captain Frederick Passow, Master, S.S. St. Paul (B21877)I would never think of giving a man in the lookout a pair of glasses.

Captain Stanley Lord, Master, S.S. Californian (U. S. Day 8)I have never believed in them. –

Captain Benjamin Steele, Marine Superintendent at Southampton

for the White Star Line (B21975)

Even the famed Antarctic explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton, presumably called to testify because of his extensive knowledge of ice and icebergs, said that he “did not believe in any look-out man having any glasses at all.” (B25058)

Why should this be? Surely a set of binoculars would be a useful asset if one’s job requires spotting things at a distance, as binoculars magnify things and bring them closer to view. The testimony of Captain Bertram Hayes, Master of the White Star Line’s Adriatic, points us to the answer:

21846. They are a source of danger, Sir. They spoil the look-out.

21847. How is that?

The look-out man when he sees a light if he has glasses is more liable to look at it and see what kind of a ship it is. That is the officer’s business. The look-out man’s business is to look out for other lights.

Having a set of binoculars in hand, then, might inadvertently take a lookout’s attention away from the “big picture” – scanning a large area ahead and to either side – or worse, causing him to delay a report while he examined the object more closely.

Second Officer Lightoller indicated much the same sentiment when he was asked if binoculars would not have helped the lookouts identify what they saw as an iceberg sooner: “He might be able to identify it, but we do not wish him to identify it. All we want him to do is to strike the bells.” (B14293) He was referring to the bell in Titanic’s crow’s nest, which the lookouts were required to strike upon sighting an object: one gong of the bell called the Bridge Officer’s attention to something off the port bow, two gongs meant something off the starboard bow, and three gongs indicated something ahead. It must be emphasized that the Senior Officer on the Bridge would be keeping his own watch, not relying entirely on the lookout. If the lookout did see something that the officer had not seen already with his own eyes, he would then observe it – using his own set of binoculars if necessary – and decide on what action to take.

(Author’s collection)

Lightoller was asked if the requirement to sound a warning before an object was identified might not cause the lookouts to hesitate for fear of making a false report. Lightoller assured his questioner that this would not be the case:

14294. (Mr. Scanlan) I will put this to you: Supposing a man on the look-out fancies he sees something and strikes the bell, and it turns out not to be anything, I should think he would be reprimanded?

He is in every case commended.

14295. (The Commissioner.) I do not understand that. Is he commended when he signals that there

is something ahead when there is nothing ahead?Yes, your Lordship.

14296. (Mr. Scanlan.) If he did it frequently in a journey would not the commendation take the form at the end of the voyage of paying him off and dispensing with his services?

Not at all. The man is not an absolute fool; he knows that if he is trying to keep a good look-out, particularly amongst ice, and he suspects he sees anything, he will strike the bell; if it turns out to be nothing he may come on the Bridge and say, “I am sorry that I struck the bell when there was nothing;” but he is invariably told, “Never you mind; if you suspect that you see anything strike the bell, no matter how often.”

And yet binoculars were provided to lookouts in some cases. Lookout George Hogg testified that he had used them on the White Star Line’s Adriatic. (B17515) Frederick Fleet said that he had them available for use during his entire four-year period aboard the White Star’s Oceanic; Archie Jewell also stated he used them on that ship.9 (B218) Able Seaman Thomas Jones stated that he had used them when he worked as a lookout on other ships, although it is not known to what ship(s) he was referring. (U.S. Day 7) And it will be recalled that lookout George Symons’ request for binoculars from Titanic’s officers was not dismissed out-of-hand. Were exceptions made aboard some White Star ships? The answer is “yes.” Lightoller stated that, “It is a matter of opinion for the officer on watch. Some officers may prefer the man to have glasses and another may not; it is not the general opinion.” (B14315)

The White Star Line was unique in that it employed men just for the job of lookouts, whereas on other ships a seaman who might be washing the decks on one watch might find himself in the crow’s nest on another. At the U. S. Inquiry (Day 5), Lightoller explained this practice:

Senator SMITH. Are experienced men usually selected for the lookouts?

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. Speaking for myself, I always select old lookout men that I know; and as a rule, the lookout men run perhaps a year in the crow’s nest in one ship. For instance the men I had with me on the Titanic had been with me on the Oceanic for years, doing nothing but keeping a lookout. They have their other special duties at other times, as well.

Senator SMITH. Do they get to be expert in detecting objects on the horizon?

Mr. LIGHTOLLER. They do. They are very smart at it, indeed. There is one man here, who has been subpoenaed, who is the smartest man I know at it.10

What this meant, in effect, was that the White Star Line had the benefit of professional lookouts – men who could be trusted to do a better job than the average seaman, and who gained experience at the job by doing nothing else. Some White Star officers – perhaps more forward-thinking than others – may have felt that such individuals could be trusted to exercise the personal discipline to use binoculars properly, and that in their hands they could be an asset in certain circumstances. While it is clear that this belief was not universal among White Star officers (we have seen the testimony of Captain Hayes of the Adriatic) there were enough who did believe in the practice, as on the Oceanic, where by three lookouts’ testimony the practice continued for four years.

The need to sound an immediate warning notwithstanding, the lookouts testified to the usefulness of being able to be certain of what they were seeing if it was far away:

Senator PERKINS. As soon as you see anything, you signal the officer on the Bridge, do you not?

Mr. HOGG. Yes, sir; you would strike the bell. But you would make sure, if you had the glasses, that it was a vessel and not a piece of cloud on the horizon. On a very nice night, with the stars shining, sometimes you might think it was a ship when it was a star on the horizon. If you had glasses, you could soon find out whether it was a ship or not. (U.S. Day 7)

Those readers who have never been to sea must pause a moment to consider that on the ocean, at night – especially from a vantage point high above the water – one can see far greater distances than is normally possible on land. A ship on or near the horizon, visible at over 11 miles distance from the crow’s nest, might appear as nothing more than a tiny pinprick of light. It’s also worth remembering that navigation lights in 1912 were not as bright as those today, nor were ships as brightly lit overall. Thus, a masthead light – the first light that would be seen over the horizon from a ship on a converging course – might well be indistinguishable from a bright star.

We have also heard Lightoller’s testimony in which he said that it was not the lookouts’ job to identify what they saw. But there were other uses for a pair of binoculars in the hands of a capable lookout. If the ship was making landfall (approaching land), it might be desirable to sight a particular light (lighthouse or lightship) as early as possible in order to ensure safe navigation. As Lightoller explained: “If I may point out, binoculars, with regard to lights, are extremely useful; that is to say, there is no doubt you will distinguish a light quicker. . . The man may, on a clear night, see the reflection of the light before it comes above the horizon. It may be the loom11 of the light and you see it sometimes sixty miles away. He may just make sure of it with the glasses, because there is any amount of time – hours; there is no hurry about them on a clear night at all. [Author’s emphasis] You make absolutely certain then about the light, and so as to be in that position we ring him up to say exactly what it is; but when it comes to derelict wrecks or icebergs, the man must not hesitate a moment, and on the first suspicion, before he has time to put his hand to the glasses or anything, one, two, or three bells must be immediately struck, and then he can go ahead with his glasses and do what he likes, but he must report first on suspicion.”

As lookout George Symons said, (B11900) “It is all according to the weather you are in. You may have a beautiful clear day or night when you see these things a long time before you see them on the Bridge. In hazy weather it does not matter, because whatever you see coming through the gloom, you report it at once.”

We see, then, that there is a clear distinction – made by officers like Lightoller, and understood by White Star lookouts – between the action required upon sighting something at a great distance under optimal visibility, and something suddenly appearing much closer. And it also depended on whether or not a particular officer trusted the lookouts on his watch. As Lightoller affirmed,

I should like to point out that when I speak favourably of glasses it is in the case of a man on whom I can rely, but if I have a man in a case like this which Mr. Scanlan speaks of, a derelict or an iceberg, who is to put the glasses to his eyes before he reports, I most utterly condemn glasses. [Author’s emphasis] The man must report first and do what he likes afterward. (B14339)

Putting aside for the moment the circumstance of something sighted at less than several miles distance, there was general agreement that binoculars were useful only after an object had been picked up by the naked eye. Seaman Thomas Jones, who was not one of Titanic’s lookouts but had served in that position elsewhere, had this to say:

Senator NEWLANDS. When you have been acting as lookout, have you been accustomed to use glasses?

Mr. JONES. Yes, sir; I have always seen them in the crow’s nest.

Senator NEWLANDS. When you were a lookout, were you accustomed to use the glasses?

Mr. JONES. Oh, yes, sir.

Senator NEWLANDS. Were they much of a help?

Mr. JONES. Not much of a help to pick anything up; but to make it out afterwards, they were.12

Titanic’s lookouts said the same thing, as the following questions and responses show:

Do you agree with this: . . . “You use your own eyesight as regards to picking up anything, but you want the glasses then to make certain of that object.” Do you agree with that? Yes. (U.S. Day 4)

Do you mean you believe in your own eyesight better than you do in the glasses?

Yes. – George Hogg (B17518)As a rule, do I understand you prefer to trust your naked eye to begin with?

Well, yes, you trust your naked eye. – George Symons (B11994)

And yet, Lookout Frederick Fleet said that he would have used them “constantly” (B17407) on the night of the 14th, if they had been available, to “pick out things on the horizon.” (B17405) And Lightoller said that during his watch he raised his binoculars to his eyes from time to time to do the same thing. When First Officer William Murdoch relieved Lightoller on the night of the 14th, conditions seemed quite favorable for spotting anything at a great distance. In Part II of this article, we’ll look at the effectiveness of different types of binoculars and whether a set in the lookouts’ hands would have made a difference in spotting objects at night.

Much of what we know about what took place on Titanic’s navigating Bridge comes from the testimony of Second Officer Charles Lightoller. Although we should be cautious of relying too heavily on the testimony of one man, there is no reason to consider anything Lightoller said as suspect. He was, by all accounts, a conscientious, no-nonsense officer and, from his testimony, we see that he was not prone to exaggeration or speculation. Lightoller had the watch on the Bridge up until 10 p.m. on the night of April 14, and from him we have a good description of what conditions were like that night and what type of watch was maintained.13

Although Titanic had two lookouts who maintained a constant watch from the crow’s nest while at sea, this did not relieve the Senior Officer on the Bridge from maintaining his own watch. Lightoller was explicit on this point in his testimony, saying, “I keep a lookout myself, and so does every other officer.” (U.S. Day 5)

Describing the last half-hour of his watch on the 14th, he said, “I took up a position on the Bridge where I could see distinctly – a view which cleared the back stays and stays and so on14 – right ahead, and there I remained during the remainder of my watch.” (B13676) By all accounts, visibility was excellent. Recounting his conversation with First Officer Murdoch at the change of watch at 10 p.m., Lightoller said, “We remarked on the weather, about its being calm, clear. We remarked on the distance we could see. We seemed to be able to see a long distance. Everything was clear. We could see the stars setting down on the horizon.” (B14274). In his 1935 book Titanic And Other Ships, he also said that “[we] commented on the lack of definition between the horizon and the sky – which would make an iceberg all the more difficult to see – particularly if it had a black side, and that should be, by bad luck, turned our way.” Captain Stanley Lord of the Californian made a similar observation: “It was a very strange night; it was hard to define where the sky ended and the water commenced. There was what you call a soft horizon.” (B7194)

It was a clear night, but also a moonless night – “pitch dark,” as Lightoller described it15. Most people who are reading this article have never experienced true darkness because of all the light pollution from artificial sources in the modern age. Hundreds of miles from land16, with no moon to cast any light on the water and only a canopy of stars for illumination, the ocean’s surface would have been very black indeed.

The ocean was also unusually calm, so much so that Lightoller said “This [was] the first time in my experience in the Atlantic in 24 years, and I have been going across the Atlantic nearly all the time, of seeing an absolutely flat sea.” (B13574) “The sea was so absolutely flat that when we lowered the boats down we had to actually overhaul the tackles to unhook them, because there was not the slightest lift on the boat [from the sea rising and falling] to allow for slacking, unhooked.” (B13577) This meant, as most students of Titanic history have read, that the officers and lookouts would be deprived of the advantage of water breaking against the base of an iceberg to give them a warning of its presence from a greater distance. Nonetheless, the officers by all accounts had no reason to be concerned about not seeing an iceberg in time.

Captain Smith had come on the Bridge for about a half-hour period at 8:55 and discussed with Lightoller the expectation that they would still be able to see even an overturned or “blue” berg: “I remember saying, ‘In any case, there will be a certain amount of reflected lights from the bergs.’ He said, ‘Oh, yes, there will be a certain amount of reflected light.’ I said, or he said . . . that even though the blue side of the berg was towards us, probably the outline, the white outline would give us sufficient warning, that we should be able to see it at a good distance, and, as far as we could see, we should be able to see it. Of course, it was just with regard to that possibility of the blue side being towards us, and that if it did happen to be turned with the purely blue side towards us, there would still be the white outline.”17 (B13617) In testimony, Lightoller estimated that, under the conditions they had that night, he would expect to see a “good-sized berg,” one “perhaps 50 feet tall,” “[a]t least a mile and a half or two miles – that is more or less the minimum. You could very probably see it a far greater distance than that. If it were a very white berg, flat topped or the flat side towards you, under normal conditions you would probably see that berg 3 or 4 miles away.”18 (B13652)

He had a pair of binoculars for his own use, but did not keep them to his eyes continually: “Occasionally I would raise the glasses to my eyes and look ahead to see if I could see anything, using both glasses and my eyes.” (B13688) He did not count on seeing any icebergs with his binoculars, though. When asked if he had ever seen ice with their help, he replied, “Never. I have never seen ice through glasses first, never in my experience. Always whenever I have seen a berg I have seen it first with my eyes and then examined it through glasses.” (B13690)

This raises the question of why binoculars, with their greater power of magnification, were not considered more useful in 1912. For the answer, we need to look at how binoculars are constructed and exactly what they do.

Binoculars are all about gathering light. In fact, they’re all about using lenses for gathering rays of light and bending (converging) them so you see a magnified picture. You see things because light rays are bouncing off what you’re looking at and entering your eye through the binoculars. The lenses furthest away from your eyes are called the objective lenses. Their job is to gather the light rays and project them – or in other words, project the image of what you’re looking at – onto the lenses at the other end of the binoculars, in the eyepiece. The lenses in the eyepiece are the ones that actually magnify the picture – the objective lenses only gather the light and project a focused image onto the lens in the eyepiece. (We’ll come back to this later.)

The only information we have on the type of binoculars used on Titanic comes from the testimony of lookout George Hogg. At the British Inquiry, when recalling the set they had used on the trip from Belfast to Southampton, he was asked about them:

“Did you notice how they were marked”?

“Theatre, Marine and Field.” “Second Officer, S.S. Titanic.” (17498)

And then,

“Was ‘Theatre, Marine and Field’ the same?”

“No, you worked them as you wanted to use them.” (17500)

The binoculars that Hogg described were a type with three different sets of lenses in the eyepieces. Each set had a different magnification, and could be rotated into position by means of a knob connected to a shaft running between the eyepieces. The user could choose between the “Theatre” setting for relatively close viewing where extreme magnification would not be necessary; “Marine” for distant viewing; and “Field” for a degree of magnification in between the two.

(Author’s collection)

Hogg’s description, although minimal, is valuable to us. Based on their type (Theatre-Field-Marine19 [T/F/M]) we know one more thing about them – they were Galileans.

All binoculars can be divided primarily into two types: Galilean binoculars and prismatic binoculars. A pair of Galilean binoculars is shown in Figure 1. This is a simplified drawing and does not accurately depict the size, shape or number of lenses. It also does not depict the rotating lenses in the T/F/M pair Hogg described, but for our purposes will suffice. In appearance, Galilean binoculars look like two short telescopes fastened side-by-side, and that’s essentially what they were. The optics are relatively simple, and involve a straight light-path from objective lens to eyepiece. Compare this to the prismatic binoculars shown in Figure 2. These use lenses in combination with a system of prisms. In these binoculars, the path of the light rays passing through the binoculars is bent several times. This lengthens the distance the light has to travel from one set of lenses to another without increasing the overall length of the binoculars. As increased magnification primarily requires increasing the length between eyepiece and objective, this design permits greater magnification without increasing size, thereby giving the advantage of a more compact, lightweight set of binoculars – an important consideration when one considers the arm fatigue that can result from holding up a heavy pair to the eyes for a prolonged period of time while trying to keep them steady.

On the other hand, a high-quality pair of Galileans would give a slightly brighter, higher contrast view than a prismatic set, although with a much smaller field of view – as much as two-thirds less than a comparable prismatic set. This means that if you were looking at the horizon, you would see a much smaller segment of it. This can be a significant disadvantage when scanning a broad expanse of ocean, because something can easily be missed or passed over before it’s noticed.

It would be imprudent not to introduce a note of caution here: There is no assurance that all the binoculars issued to Titanic’s officers were of the “Theatre-Field-Marine” type used by David Blair. There are no surviving documents that detail the specifications of those issued, and the surviving officers were not asked during testimony. The White Star name on the binoculars that Hogg described suggests that they were company issue, but they could have just as well been Blair’s own personal set, perhaps inscribed and presented to him by his family upon his appointment to the ship. Unlikely? Perhaps, but we cannot rule out the possibility.

Now let’s consider how useful a set of binoculars would have been at night. In the beginning of our discussion on binocular optics, it was stated that binoculars are all about gathering light. This is particularly relevant at night when there is much less light to begin with. Binoculars with good light transmission efficiency, which can be defined as the percentage of light that actually reaches your eye, make images seem brighter in very low light conditions. Galilean binoculars had comparatively better light transmission than prismatic types, giving a more brilliant sight picture, as noted above. By no means does this mean that they were as efficient in this regard as a good set of marine binoculars would be today, but it explains their widespread use in 1912, despite the disadvantages of a much narrower field of view20.

One contemporary source stated that, “It is generally known that a pair of ordinary Galilean field-glasses enables objects to be seen at night which are invisible to the naked eye.”21 This is true, but seeing an object is not the same as spotting it in the first place – as a lookout would have to do. In order for any given set to have true utility for night work, it required a set of much larger objective lenses combined with lesser magnification. These were called “night glasses,” and were designed “to intensify and get as much light and field as possible.”22 In other words, to give a brighter sight picture while at the same time eliminating the problem of the otherwise-narrow field of view. The trade-off, though, was that you couldn’t make things out as far away, making them less desirable for daytime use.

Were there any night glasses aboard Titanic? In Part I of this article, we read Lightoller’s testimony of the pairs carried aboard, and made no mention of any. He said there was only one set for each of the Senior Officers and the Captain, plus “[a] pair for the Bridge, commonly termed pilot glasses.” (B14327) At least one pair of night glasses has been recovered from Titanic’s wreck site, but this most likely belonged to a passenger23.

We have already established what the sea and weather conditions were in the hours leading up to the collision, but before tackling the ultimate question of whether binoculars might have been of any use to the lookouts, we need to consider what the visibility was. Lightoller reported that it remained “perfectly clear” (B13681) until he was relieved at 10 p.m. by First Officer Murdoch, although at the end of his watch he noted that it was “a little hazy on the horizon, but nothing to speak of.” (B14282) Near the end of Murdoch’s watch, this may have become slightly more pronounced; lookout Frederick Fleet testified that about 11:30 p.m. – ten minutes before the collision – he began to notice it. (B17262)24 This might be cause for concern – as Lightoller explained at the British Inquiry (13643-13647): “The slightest haze would render the situation far more difficult” if there were ice. It would also require the Officer of the Watch to call the Captain to the Bridge immediately.25

With this in mind, let’s look at the testimony Fleet gave at the British Inquiry; he was in the crow’s nest from 10 p.m. onward with Reginald Lee:

17248. Could you clearly see the horizon?

The first part of the watch we could.17249. The first part of the watch you could?

Yes.17250. After the first part of the watch what was the change if any?

A sort of slight haze.17251. A slight haze?

Yes.17252. Was the haze on the waterline?

Yes.17253. It prevented you from seeing the horizon clearly?

It was nothing to talk about.17254. It was nothing much, apparently?

No.17255. Was this haze ahead of you?

Yes.17256. Was it only ahead, did you notice?

Well, it was only about 2 points on each side.2617257. When you saw this haze did it continue right up to the time of your striking the berg?

Yes.17258. Can you give us any idea how long it was before you struck the berg that you noticed the haze?

No, I could not.

And further on:

17266. Did it interfere with your sight ahead of you?

– No.17267. Could you see as well ahead and as far ahead after you noticed the haze as you could

before?

– It did not affect us, the haze.17268. It did not affect you?

- No, we could see just as well. [author’s emphasis]

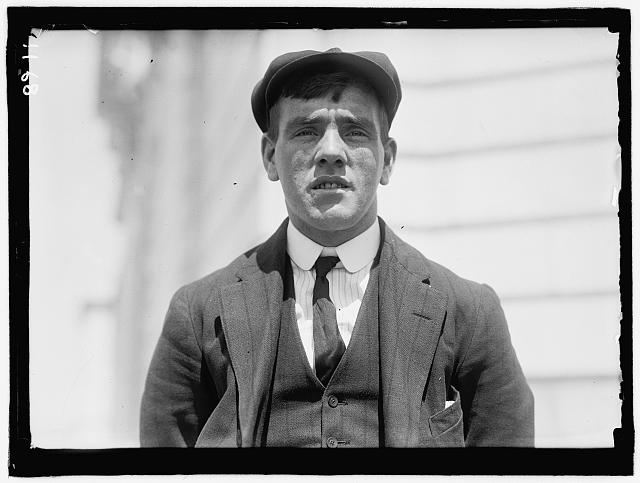

Library of Congress Photographs and Prints Division

(LC-DIG-hec-00939)

Given that the iceberg sighting fell squarely on the shoulders of Fleet and his partner, if anyone would have had a reason to use poor visibility as an excuse it would have been them. With that reasoning, it can be safely assumed that Fleet’s testimony is accurate and that the haze was not cause for immediate concern. Lee, though, contradicted Fleet when he described the haze as “extending more or less round the horizon.” (B2402) He went on to say that, “We had all our work cut out to pierce through it just after we started. My mate happened to pass the remark to me. He said, ‘Well; if we can see through that we will be lucky’.” And later on, he described the iceberg as “a dark mass that came through that haze.” (B2441). Was he exaggerating, so as to remove all doubt as to whether they should have been able to see the iceberg sooner?

The Wreck Commissioner at the British Inquiry, the Right Honorable Lord Mersey, apparently thought so:27

“My impression is this, that the man was trying to make an excuse for not seeing the iceberg, and he thought he could make it out by creating a thick haze.” (follows B17272) Lee’s story of a haze that they could barely see through is also illogical, since it would have meant that First Officer Murdoch – an experienced, capable officer – would have either had to have been asleep, grossly negligent or in complete disregard of his captain’s instructions to call him if conditions became “at all doubtful” (B13635). Fleet also denied Lee’s assertions. (B17395-17400) For these reasons, this article will proceed on the basis that Fleet’s testimony was the more accurate of the two.

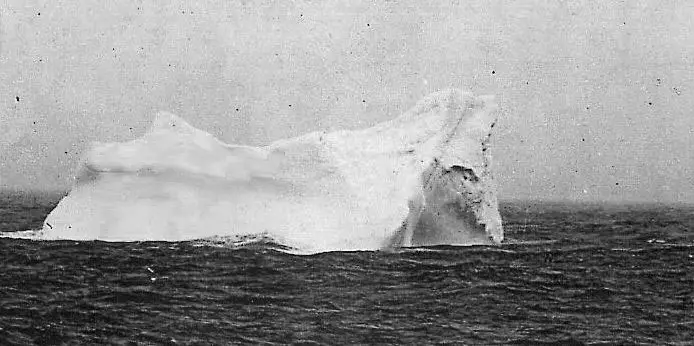

(Author’s collection)

At this point, we should pause in our discussion to consider a question: Just how large did the iceberg appear to the lookouts when they saw it? There seems to be a popular conception that the iceberg was a huge mass looming out of the darkness. But applying some trigonometry yields a far different picture. First, we can use a height of 70 feet (21.3 meters) for the iceberg, based on its observed height relative to Titanic’s Bridge as it passed by29. Icebergs are usually much wider than they are tall, so we will use a figure of 225 feet (45.7 meters) for its width.30 Next, we will use an estimate of 2,280 feet (695 meters) for how far away the iceberg was when Fleet and Lee first spotted it. Despite being pressed repeatedly for this at the post-sinking hearings, neither Fleet nor Lee would hazard a guess. However, we can estimate the distance reasonably well based on the ship’s speed and the timeline of events.31

Based on these figures, we can calculate the iceberg’s apparent size using an astronomical measurement called apparent angular size.32 Imagine standing in the center of a large circle extending out 2,280 feet in all directions. If we divide our circle into 360°, the apparent angular size is the amount of that circle – in degrees – that the iceberg would occupy if we placed it at the edge of the circle. When the iceberg was first seen, its apparent angular size would have been approximately 3¾° in width and 1¾° in height). What does this mean? Hold up your index finger at arm’s length, pointed sideways, and the outer two segments of your finger would completely cover up an iceberg that size at that distance (one finger’s width at arm’s length equals about 2°). It’s important to remember that these numbers are based on several estimates and “best guess” calculations. However, our calculations are fairly conservative and, if Fleet and Lee actually saw the iceberg further away, it would have appeared smaller yet. (And the peak of the iceberg would have been well below the visible horizon in the background long before it was seen.)

Let us assume for the moment that the horizon had been clearly visible (as we have seen, it was not). How big would the iceberg have been when it was on the horizon, 11.4 miles (18.3 km) away as seen from the crow’s nest? Contrary to suppositions that it should have been visible as a black mass silhouetted against the stars, in reality the iceberg would have appeared so small at that distance to be virtually impossible to distinguish without binoculars.33 Add the blackness of the ocean, and the inarguable fact is that the iceberg would have to get much closer before anyone would have a reasonable chance of spotting it – closer to Lightoller’s estimate of “a mile-and-a-half or two miles,” or for a very white iceberg presenting a flat side toward the ship, “3 or 4 miles” (4.8-6.4 km). Was he being unrealistic or overly optimistic? Not necessarily.

Current editions of The American Practical Navigator, one of the world’s most respected books on navigation, state that, “on dark, clear nights, icebergs may be sighted at a distance of from 1 to 3 miles” (1.6-4.8 km).34

That is no guarantee, however, and it must be understood that, despite their typical white appearance, icebergs do not reflect light uniformly or to a high degree. There is a term for this reflectivity: albedo. It refers to the surface reflectivity of the sun’s radiation, and is expressed as a number from 0 to 1. Zero means that no light is reflected, and 1 means all light is reflected. While fresh snow has an albedo of .95, (95%), glacial ice only has an albedo of .20 to .40 (20 to 40%).35 As the only available light for diffuse reflection would have been starlight, the iceberg would not have been easily seen. In addition, in light levels less than full moonlight, the human eye has a night blind spot 5-10° wide in the center of the visual field as a result of no light-sensitive receptors in this area of the retina.36 If Titanic’s lookouts had been staring straight ahead, this might well have contributed to their failure to sight the iceberg sooner than they did. As a U.S. Army Aviation training manual teaches, “Because of the night blind spot, larger and larger objects will be missed as distance increases. To see things clearly at night, an individual must use off-center vision and proper scanning techniques.”37 The tendency, if one thinks he or she sees something in the distance in dim light, however, is to stare straight at it – the worst thing to do under the circumstances.

In considering whether binoculars would have helped, let us assume that we are in the position of Fleet and Lee that night, and have a pair in our hands. How exactly are we to use them? Logic would seem to say that we should simply put them to our eyes, and see what we can see. But this would not be correct. Today there are specific techniques for making the most effective use of one’s vision – “proper scanning techniques,” as referred to above – and for using one’s binoculars when acting as a lookout. One example can be found in today’s U.S. Navy training manual on the subject:38 “To search and scan, hold the binoculars steady so the horizon is in the top third of the field of vision. Direct the eyes just below the horizon and scan for 5 seconds in as many small steps as possible across the field seen through the binoculars. Search the entire sector in 5° steps, pausing between steps for approximately 5 seconds to scan the field of view. At the end of your sector, lower the glasses and rest the eyes for a few seconds, then search back across the sector with the naked eye. When you sight a contact, keep it in the binoculars’ field of vision, moving your eyes from it only long enough to determine the relative bearing.”

Given how small the iceberg would have appeared near the horizon, it can be readily appreciated how vital such scanning techniques can be.

As noted earlier in this article, the White Star Line followed a practice that few, if any, other shipping lines did. It hired men to work just as lookouts, and nothing else. The White Star Line must have recognized that there was a benefit in having men experienced in this capacity. However, there is nothing to indicate that White Star lookouts received even rudimentary training, and such would not have been the norm in 1912 anyway. Theory, techniques and formal instruction were not part of a deckhand’s education; you learned by doing from others who already knew the ropes. That isn’t to say that White Star lookouts weren’t capable of doing a good job; as we have seen, Lightoller had genuine respect for some of them.

As we’ve also seen, binoculars of good quality do have their utility at night under conditions of good visibility, and the “night glasses” available at the time had sufficiently good optics to be an asset to those in the crow’s nest. Even without the application of specific search/scan techniques as taught today, night glasses of the quality available in 1912 might have been a help to Fleet and Lee. But ordinary Galilean binoculars, especially those of the Theatre-Field-Marine type used by the lookouts on the Belfast-to-Southampton trip, would have been much less useful. Their utility was in primarily examining something once sighted; even if used properly, they were simply not suited for scanning and searching in very low light due primarily to their narrow field of view. That does not mean they couldn’t have been used for that purpose, but the advantage they gave would have been minimal, if any. On that basis, it is doubtful whether they would have made any difference to the outcome of events on the night in question.

At the British Inquiry following the sinking, Lookout Reginald Lee made a point of testifying that binoculars were useful at night, providing they were night glasses. (B2373) But it must be recalled that the only source of illumination on the night in question was starlight, and no binoculars, even those of high quality, can amplify light – the best they can do is attempt to maximize the transmission of the light that’s available. As we’ve seen, night glasses might have been of some value as they had the twin advantages of some magnification combined with improved light-gathering capability. Would they have been enough to make a difference to alter the events of April 14? Possibly. As we have seen, the lookouts’ visibility was probably not reduced to any significant degree by the haze reported. If we accept that premise, then given the lookouts’ experience and abilities the question remains whether a good set of night glasses would have allowed them to see the iceberg farther ahead given how dark it was. At the same time, we have to remember that Titanic’s lookouts, experienced though they may have been, received no training in how to use binoculars properly at night – it is not enough simply to place a set of binoculars in someone’s hands and expect them to be used properly (although it’s unlikely that many officers would have recognized the importance of this in 1912.)

This leads us to the realization that perhaps binoculars would not have given as much of an advantage to Titanic’s lookouts as it would seem. One of the great unknowns in our “what if” is how Fleet would have used his binoculars. The only statement he made in this regard was to say, “I pick out things on the horizon with the glasses.” (B17405) We have to be careful not to read too much into this, but if Fleet had used binoculars to concentrate on the horizon without performing a sweep of the ocean below the horizon at regular intervals, it would have been of little if any benefit. As we have seen, the iceberg would have been too small to see on the horizon.

(US Navy Lookout Training Manual)

At the British Inquiry, Fleet testified that if he had had binoculars, he could have seen the iceberg in time to avert disaster. Some apparently agreed – the esteemed publication Engineering,39 for example, stated after the sinking that night glasses should be issued to lookouts. But the official findings of the British Inquiry held that glasses were “not necessary,”40 and the international Safety of Life at Sea convention that followed in 1914, and which resulted in many landmark changes to maritime safety, affirmed this as well.41 Unlike today, however, where experts in various fields are called to testify, bringing with them reams of supporting data as evidence, the British Wreck Commissioner’s Inquiry appears to have based its conclusions almost exclusively on the opinions of numerous non-White Star Line captains, none of whom gave any indication of having experience with the concept of dedicated lookouts.

Contrary to popular belief, testimony shows that binoculars were neither standard issue to the crow’s nest nor standard equipment for the lookouts, despite their use on some other White Star Line ships and, aboard Titanic, prior to her arrival at Southampton. The legend of the missing binoculars that sealed the ship’s fate is just that – a legend. The optics of the binoculars most likely used aboard the ship, had they been made available to the lookouts, had some significant limitations that made their use far from ideal in detecting icebergs at night. We have seen that the iceberg was most likely much closer, had a much smaller apparent size and was not nearly as easy to see as is commonly assumed. Combined with the above, the phenomenon known as “night blind spot” may have well been a contributing factor to the lookouts’ failure to spot the iceberg sooner than they did. But the evidence suggests that had the lookouts been provided with the same binoculars most likely used by the officers, the result would have been the same. “Night glasses” – binoculars with less magnification but greater light-gathering capability – might have given the lookouts the edge they needed, but at the same time it must be remembered that the lookouts received no training in their use.

With or without binoculars, making the most effective use of one’s vision at night requires specific training in searching and scanning techniques, so even night glasses might not have made a difference to the outcome of events on the night of April 14.

As we have seen, some White Star Line lookouts were becoming accustomed to having binoculars for their use and had begun to realize their utility. The “old school” belief of “no binoculars for lookouts” would ultimately disappear in the decades to follow. Experience gained in two World Wars through convoy work and from submarine threats demonstrated the critical need to properly equip and train lookouts. But this was still far in the future when Titanic’s lookouts were told that no binoculars were available to them. Experience had not proved their value yet, and even the events of April 14-15 were not enough of a catalyst to effect change in this area.

- 'Is this the man who sank the Titanic by walking off with vital locker key?' London Evening Standard online, August 29, 2007. http://www.thisislondon.co.uk, news article 23410094

- This was William Weller, Able Seaman.

- This was the forward end of the Forecastle Deck near or forward of the anchor-handling gear.

- As a side note, the key that Aldridge & Sons auctioned carried a tag that said "BINOCULAR BOX." Any statement that this was the key used to lock up Blair's set of binoculars is purely speculation as there is no hard evidence to indicate exactly what box this refers to. It is very likely, however, that it was on the Bridge.

- Where not otherwise specified, all testimony quoted is from either the U.S. Senate Inquiry, referenced by day number in the form 'U.S. Day 5'; or the British Wreck Commissioner's Inquiry, referenced by question number in the form 'B10732.' All testimony has been sourced from The Titanic Inquiry Project online at www.titanicinquiry.org.

- Chief Officer Henry Wilde.

- The Senior Officers were the Chief Officer, First Officer and Second Officer. They were also referred to as Bridge Officers.

- This was primarily because Junior Officers never held the position of Officer of the Watch. See “A visit to Titanic’s Bridge” by this author (Voyage 71, spring 2010).

- Quartermaster Walter Wynn, who also served on the Oceanic, confirmed this as well.

- He was speaking of lookout George Symons.

- The loom of a light refers to its indistinct presence over the horizon; the distant glow that is seen before the light itself becomes visible.

- As we will see shortly, this statement is indicative of someone who never received training in how to use binoculars for searching and scanning.

- For more information on the watch maintained on Titanic’s navigating Bridge, see “A visit to Titanic’s Bridge” by this author (Voyage, Issue No. 71, Spring 2010)

- The stays were the galvanized steel wire ropes that supported the masts.

- Ibid.

- At the point where Titanic collided with the iceberg, the nearest point of land was Cape Race, Newfoundland, which bore 336.6° true (North-northwest) on a Great Circle course at a distance of 325.1 nautical miles.

- As it turned out, Quartermaster George Rowe saw the iceberg that struck Titanic from his vantage point near the docking Bridge aft and testified that it was “the color of ordinary ice” – not dark in color (U.S. Day 7).

- This testimony is particularly valuable as it gives us a good understanding of why Titanic’s officers did not feel it was necessary to reduce speed despite the numerous ice warnings.

- Hogg was most likely giving the settings in the wrong order, as all the images of this type of binocular seen by the author have shown the settings in “Theatre-Field-Marine” order.

- This advantage would disappear in the 1930's with the advent of coated lenses. Coated lenses greatly reduce the percentage of light that reflects off the lens surface, thereby ensuring that more light is transmitted through them.

- “A Study On The Performance Of ‘Night-Glasses’ ” by Louis Claude Martin, Issue 3, 1919, of the Bulletin of the Advisory Council of the Great Britain Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, Department of Scientific and Industrial Research.

- Leckey, S.T.S., Wrinkles in Practical Navigation (19th ed., 1917) London: George Philip & Son.

- The organization RMS Titanic, Inc. (salvor-in-possession of the Titanic wreck) lists one pair online (accession no. 94/0229) as “Metal, Copper alloy; L 5¼" x W 4¾" X 2¼"; ‘LEMAIRE FAB PARIS’ is printed around eyepieces.” Such a pair is an unlikely candidate to be of White Star Line issue.

- It should be noted that it was not the responsibility of the lookouts to report such conditions, or changes in visibility, to the Bridge. Lookout Reginald Lee was emphatic about this in his testimony at the British Inquiry. (B2606)

- Lightoller, B13635-13642. Presumably, this did not apply to the slight degree of haze he noticed at the end of his watch, his unequivocal statement to the contrary notwithstanding.

- Two points on either side of the bow translates to a 45° arc with the ship’s head in the center.

- In addition, in the final arguments at the British Inquiry, Thomas Scanlon, M.P., who represented the Seamen’s and Firemen’s Union, attempted to convince the Wreck Commissioner that the haze prevented the lookouts from seeing the iceberg in time, but despite his vigorous and persistent arguments, Lord Mersey was not swayed.

- The photo was taken in the area of the sinking five days from the German liner Bremen. It matches the description of Titanic Seaman Seaman Joseph Scarrott, who said that it looked like "the Rock of Gibraltar looking at it from Europa Point" (British inquiry, Day 2).

- Testimony of Quartermaster Alfred Olliver, U.S. Day 7.

- This width-to-height ratio is based on the image shown above.

- Based on a recent analysis by Sam Halpern, “She Turned Two Points In 37 Seconds,” it can be calculated that the lookouts would have seen the iceberg at a distance of about 2,280 feet, or a little over one-third of a mile: (5 seconds for awareness of something ahead + 5 seconds decision/reaction time + 30 seconds from 3 rings of bell to first helm order + 20 to 25 seconds helm order to collision) x ship’s speed of 22 knots = 2,280 ft. (Sam Halpern, a Titanic researcher of note, has a long history of impeccable and unbiased analyses of mathematical and navigational data and as of this writing his work is among the most respected in this field.)

- Apparent Angular Size = (Linear Width ) Distance) x 57.3, where Apparent Angular Size of an object is expressed in degrees.

- For an iceberg 70 feet tall, its apparent angular height on a distinct horizon would have been about 3½ arc-minutes. Objects of less than several arc-minutes are normally indistinguishable to the human eye.

- The American Practical Navigator, online publication No. 9, National Imagery and Mapping Agency, Bethesda, Maryland, 1995 ed., p 469.’

- Budikova, Dagmar (Lead Author); “Albedo” In Encyclopedia of Earth online. Washington, D.C.: Environmental Information Coalition, National Council for Science and the Environment. First published November 21, 2006; last revised January 24, 2010, http://www.eoearth.org/article/Albedo

- The Eye and Night Vision, American Optometric Association, http://www.aoa.org/x5352.xml

- U.S. Dept of the Army Training Circular No. 1-204, “Night Flight Techniques and Procedures,” December 1988, Chapter 21, pp 5-6.

- NAVEDTRA 12968-A, pp 10-11, 14.

- “Sea-bound Traffic and the Titanic Disaster” by R. P. Hobson. Engineering, vol. 43 (June, 1912), p 433.

- British Wreck Commissioner’s Inquiry, Findings of the Court, Question 11B. It should be noted that in making this determination, neither Titanic’s surviving Senior Officer (Lightoller) nor anyone else was asked any questions at all as to the type or specifications of the binoculars on the ship.

- Specifically, the SOLAS convention ruled that “in general the use of binoculars for lookout men is not recommended.” (Safety Of Life At Sea – Hearings before the Committee on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate 63rd Congress, April, 1914, pp. 17, 190)

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Sam Halpern and Bob Read for assisting with the angular calculations involved in this article, and thanks to Peter Abrahams for sharing information on optics and binoculars of Titanic’s era. Any technical, factual or mathematical errors in any of the above areas remain the sole responsibility of the author.

This article originally appeared in Voyage, the quarterly publication of the Titanic International Society, issues 72/73, summer and autumn 2010. Reprinted here courtesy of TIS.

Comment and discuss